In the 1940s, Paul F. Lazarsfeld defined international communication as a study of the “processes by which various cultures influence each other” (Lazarsfeld 1976, 485). The term culture has been defined in a variety of ways over the years. An all-encompassing definition of culture was given by Kroeber: culture “is a way of habitual acting, feeling and thinking channeled by a society out of an infinite number and variety of potential ways of living” (Kroeber 1952, 136).

Intercultural media effects denotes the idea of change or modification to the culture of individuals living in a given society induced as a result of their exposure to media content produced in another society. Since television is still the most popular and prevalent form of entertainment media around the world, this article will be confined in scope to the cross-cultural impact of entertainment television. The question here is: Can the culture of individuals in a given society be changed or modified as a result of their exposure to entertainment television programs produced in another society?

Strong Effect Paradigm

The various perspectives about this topic that have emerged during the last 40 years can be categorized according to their assumed strength of impact: strong impact and contingent impact. When critics of imported television discuss its influence, they do so within the framework of cultural imperialism (CI; Schiller 1969; 1991). According to its proponents, CI is “a verifiable process of social influence by which a nation imposes on other countries its set of beliefs, values, knowledge and behavioral norms as well as its overall style of life” (Beltran 1978, 184).

Television is seen by CI proponents as the means through which powerful states influence weaker states. CI advocates utilize an inductive process for drawing conclusions about the contemporary international intentions and behaviors of states using conspiracy theory as their premise (see Schiller 1976). CI proponents set out to document the presumed conspiracy that underlies the behavior of powerful states in their quest to dominate weaker states. The conspiracy assumption itself is most probably a projection of the historical motivations of rulers (i.e., kings, princes, emperors, and governments) as observed via their documented predatory behaviors throughout human history. CI draws especially on the economic dependencies that existed between European colonizers and their colonies. Colonialism is seen as a direct antecedent of the economic dependency that characterized the relationship between colonies and colonizers with the former depending on the latter. The economic inequities among states observed in the postcolonial era that followed World War II are seen as a direct effect of the desire of more powerful states to maintain their control over weaker states. Assuming conspiracy and aiming to uncover it in the postcolonial era, CI advocates perceive stronger states as intending to perpetuate the economic dependency of weaker states that prevailed during colonial times. They believe that the mass media (including television) are the remote-control tools with which more powerful countries dominate the populations of weaker countries. According to this perspective, the specific role of the mass media is to alter the culture of the local inhabitants of weaker countries and modify their behaviors in ways that benefit the more powerful countries.

The advocates of this perspective claim that CI is an effect that stems from the documented flow of television programs from western countries and the mere presence of these programs in the television schedules of developing countries. According to Elasmar and Bennett (2003), with respect to the influence of imported television, the implicit assumptions of the CI process are: (1) the presence of foreign programs in domestic TV schedules will lead domestic audience members to watch these programs; (2) imported television content will be similarly processed by all audience members who are exposed to it; and (3) exposure to imported television programs will result in strong and homogeneous effects across audience members.

Contingent Impact Paradigm

Several perspectives that challenge the CI framework have emerged over the years. Each addresses one or more of the implicit CI assumptions noted earlier. In the hybridization approach, researchers take a macro approach to the topic of imported media effect. Pieterse defines structural hybridization as “the emergence of new practices of social co-operation and competition” and cultural hybridization as “new translocal cultural expressions” (Pieterse 1995, 64). The implicit argument here is that imported media do not have a homogeneous impact on their viewers. In lieu of the cultural domination and destruction arguments made by cultural imperialism advocates, proponents of the hybridization perspective believe that the likely impact of imported media is the creation of hybrid cultures among its consumers.

The cultural proximity perspective focuses on the audience’s active decision to select and consume imported television content. Straubhaar advances the notion that, when given a choice, audience members are more likely to select imported TV programming that is embedded with values more similar to their own: “Audiences in many countries are . . .clearly expressing a preference for both national production and, particularly in smaller countries, for intraregional exports, seeking great cultural proximity at both levels” (Straubhaar 1991, 55). Thus, the cultural proximity perspective focuses on the barriers that prevent imported media from having a wide-ranging and homogeneous effect on its viewers. The implicit argument here is that strong effects are impossible since the content that is chosen is embedded with values similar to one’s own.

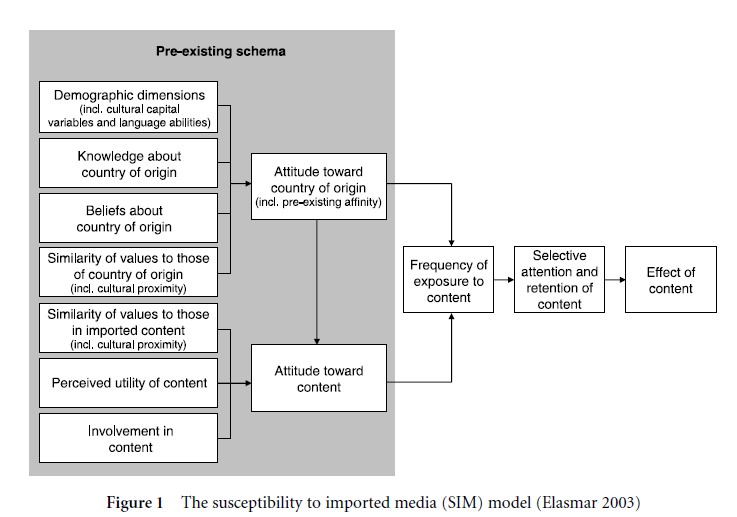

Figure 1 The susceptibility to imported media (SIM) model (Elasmar 2003)

The susceptibility to imported media (SIM) perspective focuses specifically on the variation that exists among individual audience members of imported television programs (Elasmar 2003). The SIM model is designed to: (1) illustrate the process of imported media influence, (2) understand the conditions under which imported media can be influential, and (3) identify the type of effect (i.e., affective, behavioral, etc.) that imported media are most likely to achieve. The idea here is that some viewers are going to be less susceptible while others more susceptible to being influenced by imported TV programs. The viewers’ susceptibility will depend on their pre-existing beliefs and attitudes and on the interrelationships that exist among specific cognitive components (see Fig. 1).

The term “schema” is commonly used in the field of social cognition to denote the set of cognitive components that are activated in response to a specific social stimulus. According to the SIM model, one needs to understand the interrelationships among specific cognitive components present in a viewer’s schema in order to determine whether this viewer will be affected when exposed to specific imported entertainment media content. With respect to the type of effect likely to occur as a result of a viewer’s exposure to imported television content, the SIM model ranks effect types from those most likely to occur to those least likely to occur as follows: knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and values. For all these effect types, the literature suggests that the most likely impact of imported television programs would be that of reinforcing pre-existing states. The least likely impact would be to radically change these pre-existing states.

The perspective of media-accelerated cultural diffusion focuses on a conspiracy-free label that ought to be given to the influence that might result from a viewer’s exposure to imported media content. Elasmar (2003) proposes the term “media-accelerated cultural diffusion” when such an impact is detected. This notion is an extension of the cultural diffusion perspective that existed in anthropology in the early 1900s. Cultural diffusion or borrowing occurs when an individual “faced with a situation in which the shared habits of his own society are not fully satisfactory, copies behavior which he has observed in members of another society” (Murdoch 1971, 325).

How frequently does cultural diffusion occur? Smith contends that “in almost everything we use in our daily life and in most of the things we do . . . we display our indebtedness to the world’s civilization in its full range” (Smith 1933, 8). Writing in the early 1900s, long before the advent of worldwide electronic communication networks, Smith aptly states that: “The diffusion of culture is not a mere mechanical process such as the simple exchange of material objects. It is a vital process involving the unpredictable behavior of the human beings who are the transmitters and those who are the receivers of the borrowed and inevitably modified elements of culture. Of the ideas and information submitted to any individual only parts are adopted: the choice is determined by the personal feelings and circumstances of the receiver” (Smith 1933, 10). He adds that the ideas that are borrowed are transformed by the receiving communities as they adapt them to fit their particular needs. While throughout history humans have interpersonally channeled cultural diffusion, today electronic media that span the globe at tremendous speeds can potentially contribute to the diffusion of culture. When exposure to imported television programs is found to influence some aspect of a local viewer’s culture, an appropriate label for this effect is media-accelerated culture diffusion (MACD).

References:

- Beltran, L. R. S. (1978). Communication and cultural domination: USA–Latin American case. Media Asia, 5, 183 –192.

- Elasmar, M. G. (2003). An alternative paradigm for conceptualizing and labeling the process of influence of imported television programs. In M. G. Elasmar (ed.), The impact of international television. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 157–180.

- Elasmar, M. G., & Bennett, K. (2003). The cultural imperialism paradigm revisited: Origin and evolution. In M. G. Elasmar (ed.), The impact of international television. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 1–16.

- Kroeber, A. L. (1952). The nature of culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lazarsfeld, P. (1976). The prognosis for international communications research. In H. Fischer & J. C. Merrill (eds.), International and intercultural communication. New York: Hastings House, pp. 474 – 484.

- Murdoch, G. P. (1971). How culture changes. In H. L. Shapiro (ed.), Man, culture and society. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 319 –332.

- Pieterse, J. N. (1995). Globalization as hybridization. In M. Featherstone, S. Lash, & R. Robertson (eds.), Global modernities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 45 – 68.

- Schiller, H. I. (1969). Mass communication and American empire. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Schiller, H. I. (1976). Communication and cultural domination. Armonk, NY: International Arts and Sciences Press.

- Schiller, H. I. (1991). Not yet the post-imperialist era. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8, 13 –28.

- Smith, G. E. (1933). The diffusion of culture. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat.

- Straubhaar, J. (1991). Beyond media imperialism: Asymmetrical interdependence and cultural proximity. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8, 39 –59.