The economics of advertising are crucially important in understanding the history of modern mass media as well as their continued development. Sometimes called “indirect” funding (compared to the “direct” funding provided by consumers to such media as books and recorded music), advertising as an economic institution involves several different industries and collectives. Advertising’s influence as a revenue stream for media is arguably a more significant social force than the symbolic power of explicit commercial content like television advertisements. Advertising revenue fundamentally influences not just the placement of ads in the media, but also the nonadvertising content and dissemination of funded media. This is increasingly true even for media and cultural forms that traditionally have not depended upon the generation of advertising revenue, such as theatrically released films and video games.

Development Of Advertising’s Economic Links To Media

In the history of modern media, advertising has grown from a supplemental source of media income, to a dominant source, to (in some cases) an exclusive source. Although early newspapers and magazines carried advertisements, the main source of revenue was from readers. This changed with industrialization and the establishment of advertising agencies, brand marketing, and national markets, all of which encouraged companies to place ads in new and established media to market their goods and services. In the United States, by approximately 1900 both the newspaper and magazine industries generated a majority of their revenue from advertising rather than from readers. This shifted the basic economic logic of the media, as media users went from being the direct revenue providers – the customer/market of media – to being the product sold to the media’s larger customer, advertisers. Today, print media such as newspapers and magazines average about 65–75 percent of their revenue from advertising.

Although it was not clear during radio’s early development that it would be advertising-supported, in the US through a variety of powerful commercial and policy maneuvers the medium eventually more fully embraced an advertising revenue system than did even the earlier print media. Following this, television developed as a fully advertising-supported system from the beginning. Virtually 100 percent of for-profit broadcasting revenue, then, is generated from advertising. The economic influence of advertising was further shown in media that were created to only carry advertising and promotional messages; such media include billboards, catalogs, and other forms of direct mail. More recent forms such as websites may be entirely funded by advertising, or exist only to serve as advertising (such as websites for products). In television, infomercials – a half-hour block of time bought by an advertiser – serve a similar function and have become an expected source of income for both local stations and national networks.

Economic Figures And Trends

Industry summaries of advertising-spending trends and amounts may factor in measured and/or unmeasured media. Measured media include traditional mediated advertising venues: print media such as newspapers and magazines, broadcast and cable entertainment media, billboards and the growing marketing venue of the Internet. Unmeasured media spending typically involves marketing and promotional activities such as direct mail, couponing, catalogs, and sponsorship at special events.

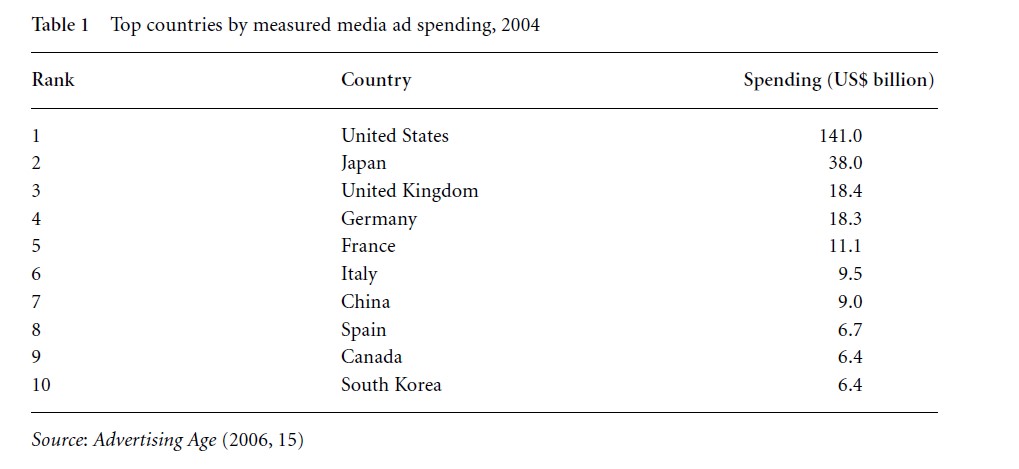

The economic scope of global advertising is enormous and ever growing. Global spending on advertising increased in the US from under $450 billion in 2001 to approximately $640 billion projected for 2007 (Coen 2006). The US is by the far the top country in terms of advertising spending, accounting for nearly half of global revenue. However, spending in many other countries keeps pace with ad growth in the US and in some, such as China, it is growing at a significantly faster rate (Table 1).

Table 1 Top countries by measured media ad spending, 2004

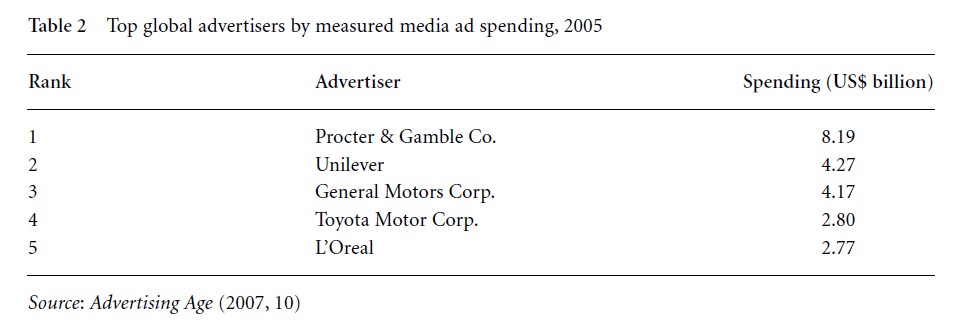

The advertising industry involves an interplay of three powerful economic players: advertisers, advertising agencies, and media companies. Even though individuals can be advertisers – especially through classified advertising in newspapers and websites – easily the most visible and influential advertisers are multinational conglomerates, with the top companies spending billions each year to maintain a global promotional presence and establish a coherent and imposing global brand image (Table 2).

Table 2 Top global advertisers by measured media ad spending, 2005

Advertising agencies are engaged in a variety of activities, including campaign creation and marketing research. An important function is media planning and buying, in which the advertising agency serves as a liaison between the advertiser and media in which ads are to be placed. Often compensation to the agency involves a percentage of ad placement costs charged by the media. One characteristic of modern advertising agencies is the globalization of very large advertising/marketing organizations, often holding organizations that own several powerful, globally spanning individual advertising agencies. Not only do these global holding organizations control many full-service agencies that integrate many marketing, promotional, advertising, and public relations functions, but their huge size allows them leverage in their negotiations with media companies. Illustrating a heavy ownership concentration in advertising agencies, the top four marketing organizations – Omnicom Group, WPP Group, Interpublic Group of Cos, and Publicis Groupe – through the advertising agencies that they owned, accounted for over 55 percent of 2004 measured media billings in the United States (Advertising Age 2006, 45).

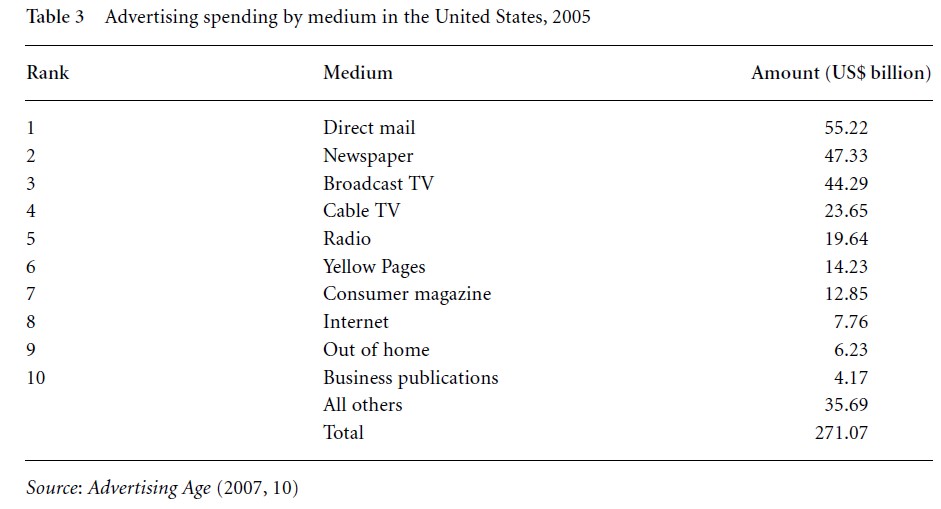

In terms of advertising spending by media, in the US direct-mail advertising receives a higher revenue than any other single medium, followed by newspapers and televisual forms. Although the Internet is still fairly low on the list, its growth has typically been much greater than average, and traditionally powerful advertising media such as newspapers and broadcast network television find that their growth is lower than average for advertising revenue across all media (Table 3).

Table 3 Advertising spending by medium in the United States, 2005

Table 3 Advertising spending by medium in the United States, 2005

Large media companies such as Time Warner, Viacom, and Disney account for a large share of the advertising revenue. In fact, companies such as these are both among the top receivers of advertising revenue (through the ad-supported media companies they own) and the top spenders of advertising (through the marketing of their own media products such as theatrical films and DVDs). Such multiple roles by large conglomerates encourage the creation of large-scale cross-promotional campaigns and licensing.

Defenses And Criticisms Of Advertising’s Economic Influence

Advocates for the benefits of advertising’s economic effect contend that advertising lowers prices because it encourages mass production and thus economies of scale. Proponents also argue that advertising stokes economic growth by encouraging spending. The benefits of “free” media – media funded primarily by advertising, with no direct and obvious economic cost to media users – also has been highlighted, especially with broadcast media and “controlled circulation” magazines distributed without immediate cost to targeted markets.

Criticisms of advertising’s effect upon a nation’s economy include the barrier to entry for new goods and services that the expectation of large advertising budgets creates. A similar argument is made about the emphasis on political advertising, especially in countries with few restrictions on such paid practices. A common charge is that the high expense of advertising spending during a political campaign severely limits the potential pool of viable candidates for office.

Much critical work has been devoted to understanding how advertising as an economic force has influenced – and continues to influence – the ideological and democratic limitations of media. Critics such as Bagdikian (2000) and Baker (1994) have argued that advertising encourages the growth of large and powerful media monopolies. When media companies grow, they can offer advertisers large coverage and efficient placement – exploiting economies of scale – and thus disadvantage smaller media companies with less reach. Others have noted the explicit attempts by advertisers to remove ideas critical of advertisers or advertising in media by withdrawing advertising revenue, or the susceptibility to self-censorship by media that the potential threat may encourage. Ideas that are critical of commercialism generally – or even overly negative about the larger institutions or norms of society – may likewise find resistance in advertising-supported media. The exclusionary tendencies of advertising media also extend to the intended audiences. Generally, audiences who have disposable income, are willing to spend that income, and are willing to try many different kinds of brands are the ideal type of audience that advertisers would like to reach; advertising-supported media may tend to emphasize the creation of content that appeals to such audiences, thus excluding nonadvertising-desirable audiences. On the other hand, advertising encourages entertainment-oriented content in media to keep ratings/readership high, and consumerist messages to create a receptive climate for selling messages.

The economics of advertising will continue to change, perhaps radically, as media become cluttered with advertising, advertising agencies embrace integrated marketing communications, traditional media become increasingly desperate to prevent further erosion of their share of available advertising spending, and digital technologies integrate more fundamentally with traditional media forms. The concept of branded entertainment, where advertisers integrate the selling function in traditionally autonomous entertainment and news forms, is a trend of the new promotional millennium and one that changes the economic conventional wisdom of advertising. More specifically, product placement and sponsorship are increasingly found in various media, including broadcast media. These promotional strategies alter the nature of advertising deals with such media, making them more expansive in scope by entering the system during the early stages of media content development and production. Feedback-oriented digital technologies such as on-demand viewing and target marketing techniques like database marketing and mining potentially make media companies into audience-information brokers that collect and leverage different audiences’ media consumption patterns. Media companies that are both major carriers of advertising and major advertisers for their own products will continue to blur the distinctions between the traditional categories of advertisements and nonadvertising media content.

References:

- Advertising Age (2006). Fact Pack 2006, supplement (February 27).

- Advertising Age (2007). Ad Age Annual, pp. 7– 46 (January 1).

- Bagdikian, B. H. (2000). The media monopoly, 6th edn. Boston: Beacon.

- Baker, C. E. (1994). Advertising and a democratic press. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Coen, R. J. (2006). Robert Coen Presentation on Advertising Expenditures June 2006. New York: Universal McCann.

- Frith, K. T., & Mueller, B. (2003). Advertising and societies: Global issues. New York: Peter Lang.

- Leiss, W., Kline, S., Jhally, S., & Botterill, J. (2005). Social communication in advertising: Consumption in the mediated marketplace, 3rd edn. New York: Routledge.

- McAllister, M. P. (2005). Television advertising as textual and economic systems. In J. Wasko (ed.), A companion to television. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 217–237.

- Pope, D. (1983). The making of modern advertising. New York: Basic Books.

- Shaver, M. A. (2004). The economics of the advertising industry. In A. Alexander, J. Owers, R. Carveth, C. A. Hollifield, & A. N. Greco, Media economics: Theory and practice, 3rd edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 249 –263.

- Soley, L. (2002). Advertising censorship. Milwaukee: Southshore.