The term “exemplification effect” describes the influence of illustrating and aggregating case descriptions in media presentations on the recipients’ perceptions of issues. Aggregating case descriptions emerges whenever media coverage presents any kind of generalizing claim about natural or social phenomena and an arbitrarily selected sample of single cases to illustrate the issue at hand. General claims (e.g., “growing poverty in society”) often are supported by presenting quantitative information (so-called “base-rate information”) about a large number of cases (e.g., statistics about poverty).

Single case information often describes events, episodes, individual experiences, or testimonials (e.g., the fate of an individual homeless person, testimonials of homeless, etc.). This suggests that the general claim can and should be applied to events or subjects beyond the displayed cases. Therefore, single cases serve as examples (also called “exemplars”) that illustrate (i.e., exemplify) the general claim about the total population of phenomena (the exemplified) from which these cases are drawn. However, as a rule, the recipients’ conceptions of frequency, urgency, or potential risk of the events covered are strongly influenced by the number and type of the exemplars, whereas the general information often is ignored.

Single Cases, Examples, And Communication

From an epistemological perspective, all events and objects have distinctive features: no two cases are truly alike. Nevertheless, we can combine individual cases into classes of cases with similar or equal characteristics. This grouping strategy is a basic tool in human cognition (categorization). If we select a case out of such a class of cases and regard it as representative for all other cases of the class, we use it as an example, assuming that it is typical or representative for other unobserved cases (Zillmann 1999). Thus, an individual case becomes an example whenever an observer generalizes from an individual observed case to other unobserved cases, or if a communicator uses the individual case as an illustration of a general statement (Daschmann 2001; Zillmann 2002).

The use of examples is frequently based on a persuasive intention – the aim is to present the general claim particularly convincingly and impressively – and obviously, episodic information has this quality. In the mass media, the use of examples is even on the increase: journalists have to make their contributions vivid, comprehensive, and interesting. Therefore, they prefer episodic information and illustrating single cases: this type of information is easy to understand and obviously more vivid and more dramatic than pallid and abstract general information. Iyengar (1991) showed the frequent use of episodic information in television. Zillmann et al. (1992) pointed out that the combination of abstract general information and exemplifying single cases is a prototypical format of media contributions. Content analyses document that examples frequently present a biased selection of cases, consistent with the news report’s focal contention and often selected due to their dramatic and emotional potential (Daschmann & Brosius 1999; Zillmann & Brosius 2000). Biased selection of examples in the media is a particular problem, since there are no professional rules for exemplification in journalism – besides the self-evident requirement that the examples have to be true.

Research Designs And Findings

Most experiments in the effects of exemplars use the following design: subjects read, hear, or watch news coverage containing statistical information (base-rate) about the focused issue (in most studies, information about the climate of opinion provided by survey results) and a sample of five to nine examples illustrating the focused issue (in most studies, testimonials by a few individuals that articulate their personal opinion). While the baserate information is kept constant over all experimental versions, the number and content of the exemplars is varied: in one version, the pro–contra distribution of the exemplars is in line with the general claim of the base-rate data, in the other version it contradicts the base-rate. After the presentation, subjects are asked to estimate the frequency and urgency of the issue (in most studies, the climate of opinion), as well as to indicate their own opinion about the topic.

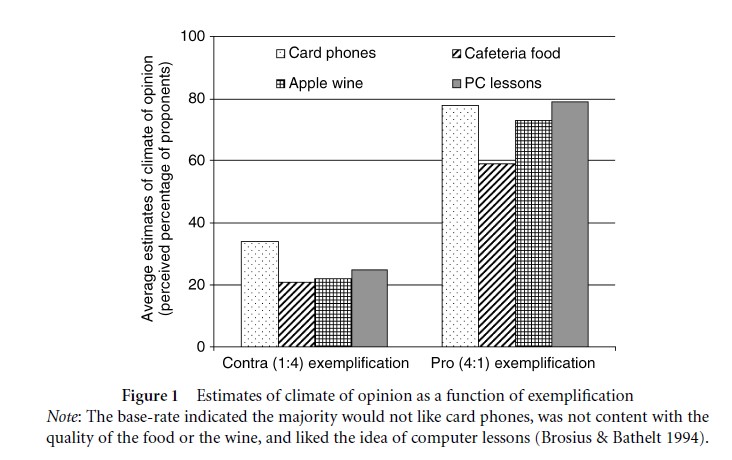

Figure 1 Estimates of climate of opinion as a function of exemplification

For example, Brosius & Bathelt (1994) presented radio reports about four different issues. Each of the reports contained five testimonials (examples). The pro–contra distribution of the examples was varied in two versions. Subjects’ estimates of the climate of opinion were in line with the number of exemplars while ignoring the base-rate data (Fig. 1).

Exemplification Effects – A Research Overview

In the 1990s, findings in social psychology led to exemplification research as a new branch in communication science. The impact of exemplification has been investigated in nearly 40 studies (for an overview, see Zillmann & Brosius 2000; Daschmann 2001), mainly in the US and Germany. Only one of these studies did not confirm exemplification effects as described above. All other investigations found an impact of the distribution of exemplars on perceived climate of opinion, on estimates of frequency of occurrence, on urgency of the issue, or on perceived risk ratio. In addition, several studies found an influence of exemplification on the personal opinion of the recipients.

The more examples are presented, the more one-sided their distribution is. The more dramatic, extreme, and emotional the displayed cases are, the stronger are the effects. Presentation features such as personalization, vividness, or direct speech increase these effects, too. Exemplification effects are reproduced in different kinds of media (radio, television, and print). Most studies focus on exemplification in nonfictional media coverage, mainly in the news, but confirm the effect for very different issues, e.g., the introduction of new technologies, the threat of crime, the safety of means of transport, including social topics such as the poverty of farmers as well as current political topics and questions of fashion or taste (Gibson & Zillmann 1998). For all issues, exemplification effects are confirmed, some studies document effects even two weeks after exposure. As yet, there are no systematic hints concerning interactions of the effect with socio-demographics like age, gender, or education. Different psychological traits or states, e.g., empathy, involvement, knowledge, preconceptions, or former experiences also do not interact with exemplification effects. In addition, exemplification effects seem to occur unconsciously: even when subjects regard the presented examples as a nonrepresentative sample, their judgments are influenced by the examples.

Causes Of Exemplification Effects

Findings in social psychology indicate that most people ignore available statistical information when forming judgments about frequencies, probabilities, or risk (base-rate fallacy) but rely for their judgments on information about a few nonrepresentative cases. Obviously, the relevance of information for human cognition is in contrast to its diagnostic value as seen from an epistemological point of view. Social psychologists assumed that due to their vividness examples are more available in memory and therefore have a stronger impact on memory-based judgments. Empirical studies did not support this hypothesis. Instead, it was found that many other presentation features, such as direct speech or personalization, or characteristics of the examples such as credibility or perceived representativeness, as well as characteristics of the recipients such as preconceptions or involvement also did not satisfactorily explain the findings.

More recent theories (Brosius 1995; Zillmann & Brosius 2000; Zillmann 2002) assume that the exemplification effect is rooted in a basic cognitive mechanism of inductive learning (“episodic affinity”) from episodic case information (Daschmann 2001). The mechanism is a cognitive tool, increasing the ability to draw general conclusions based on everyday experiences. The “heuristic” may be seen as a product of evolutionary development because it is helpful and reasonably correct when general conclusions are drawn from typical cases. However, if applied to untypical cases, misperceptions and wrong conclusions are the rule. In the process of reception of media coverage, the heuristic may thus lead to inadequate judgments due to the special type of examples used in the media.

This hypothesis implies consequences for journalism: since journalists cannot do without examples due to their advantages for presentation, they should use them in a more responsible and representative way (Meyer 2002). They should present less extreme examples and include counterexamples in their contributions. On the other hand, recipients should be aware of the biased exemplification presented in the media and try to validate their judgments and conceptions by including further information sources.

While the existence of exemplification effects is well-confirmed, there are still questions open concerning the connections to other approaches in media effects research. These concepts describe different effects but can be based on the same cognitive mechanism. With respect to the methods and issues used, further research is necessary. Because nearly all studies tested students only, there is a lack of field research that could improve the external validity of the findings. There should be a greater focus on investigations of exemplification within domains of communication other than news coverage (commercials, entertainment, etc.). In addition, surveys of journalists about the selection and use of examples are necessary.

References:

- Brosius, H.-B. (1995). Alltagsrationalität in der Nachrichtenrezeption [Everyday rationality in news reception]. Opladen: Westdeutscher.

- Brosius, H.-B., & Bathelt, A. (1994). The utility of exemplars in persuasive communications. Communication Research, 21, 48 –78.

- Daschmann, G. (2001). Der Einfluss von Fallbeispielen auf Leserurteile: Experimentelle Untersuchungen zur Medienwirkung [The impact of examples on readers’ judgments: Experiments in media effects research]. Constance: UVK.

- Daschmann, G., & Brosius, H.-B. (1999). Can a single incident create an issue? Exemplars in German television magazine shows. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 76, 35 –51.

- Gibson, R., & Zillmann, D. (1998). Effects of citation in exemplifying testimony on issue perception. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 75, 167–176.

- Iyengar, S. (1991). Is anyone responsible? How television frames political issues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Meyer, P. (2002). Precision journalism: A reporter’s introduction to social science methods, 4th edn. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Zillmann, D. (1999). Exemplification theory: Judging the whole by some of its parts. Media Psychology, 1, 69 – 94.

- Zillmann, D. (2002). Exemplification theory of media influence. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 19 – 41.

- Zillmann, D., & Brosius, H.-B. (2000). Exemplification theory. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Zillmann, D., Perkins, J. W., & Sundar, S. S. (1992). Impression-formation effects of printed news varying in descriptive precision and exemplification. Medienpsychologie, 4, 168 –185.