The issue of media conglomeration, or the phenomenon of a vast amount of cultural (media) production being controlled by a relatively small number of corporations, has generated heated debates among communication scholars, policymakers, and industry practitioners. In these debates, the concept of media conglomeration primarily refers to ownership structures within media and communications industries, as well as to the nature and organization of this type of cultural production. The phenomenon of media conglomeration, though, touches upon a much broader set of interrelated issues – ranging from questions on diversity, competition, and control in a tightly oligopolistic market, to concerns over the wider societal implications of a situation where huge conglomerates dominate the global communications system.

Drawing upon public sphere theories, scholars working within a critical research tradition have been asking questions about how far and at what price a communication system can be dominated by a handful of corporations, and how this might affect the diversity of information and argument needed for effective and well-informed citizenship (McChesney 1997; Bagdikian 2004). Sharp political economic analyses on how the corporate structure and strategy of media conglomerates tend to homogenize cultural production and restrict critical media content have been opposed by advocates of the free market (Compaine 2005). Media conglomeration is also an important concept in the academic field of international communication and in debates on media, internationalization, and globalization (Thussu 2000). Because much of today’s communications industry is under the control of multinational corporations with cross-media activities in most parts of the world and with their headquarters in the USA, western Europe, Australia, or Japan, the issue of media conglomeration is often associated with older arguments about Americanization, Eurocentrism, or cultural imperialism (Tomlinson 1999).

Background

Although an unparalleled series of international acquisitions and buy-outs of media and entertainment companies in the 1980s and 1990s fueled the debate, it is clear that the issue of media conglomeration is not a new phenomenon. During the second half of the nineteenth century, new technologies such as the telegraph, facilitating the transfer of information over a long distance, created the first modern media corporations with an international scope. Telegraph operators, advertising companies, and world news agencies emerged and spread their activities to many parts of the world. In the twentieth century, the growth of other new media sectors went hand in hand with vertically integrated and internationally active companies. The film industry, for instance, quickly saw the emergence of oligopolistic structures, first with French companies (Pathé, Gaumont) and later with Hollywood-based majors (Paramount, Warner Bros., etc.), which tried to control most levels of the industry (production, distribution, exhibition), increased their interests in the wider leisure industry (music, radio, etc.), and operated in an international environment. In the postwar period, the filmed entertainment industry saw several waves of mergers and concentration, completely transforming the production, distribution, and exhibition of motion pictures. Mainly from the 1950s onwards, with the advent of television, Hollywood majors diversified their activities and increased their interests in the broader entertainment industry, including the production of television series or the exploitation of theme parks (Wasko 2003, 59). In the mid-1960s, a major wave of takeovers took place, leading to several Hollywood studios being absorbed by ever-larger media and entertainment formations (e.g., Paramount was taken over by Gulf and Western in 1966). In the 1980s, the rapidly expanding global entertainment market led to a new wave of concentration. The availability of new delivery systems, the development of new markets and technologies (e.g., home video, pay-TV), combined with a more liberal regulatory policy (or deregulation), all resulted in a further cycle of mergers. A spectacular flurry of concentration moves emerged, mainly because film and television companies, as well as other players with interests within the audiovisual scene, sought to gain control of the new technologies and the expanding entertainment market. In 1985, for example, Twentieth Century Fox was engulfed by Rupert Murdoch’s global entertainment empire News Corporation. In 1989 Sony purchased Columbia for $3.4 billion. One year later, another Japanese electronics manufacturer, Matsushita, purchased MCA/Universal for $6.9 billion, while in that same year Warner Communications and Time Inc. merged.

This trend toward greater corporate entities did not stop in the 1990s; more recently, there have been spectacular mergers, such as the creation of AOL/Time Warner in 2001, considered to be the largest entertainment group in the world. This very big, vertically integrated media corporation with total revenues of $38 billion (in 2005) has a dominant position in the media, communications, and entertainment sectors, ranging from Internet services (mostly under the heading of AOL) to film production, distribution and marketing, publishing, music, and cable and network activities. The group’s most well-known subsidiaries are Warner Bros. Pictures, New Line Cinema, AOL, CNN, Time magazine, and HBO, but many more brands and companies fall under the umbrella of AOL/Time Warner. Although most of its activities are located in the USA, it is clear that the corporation has worldwide interests, not only for the sales of its products, but also through a structural network of control and ownership of divisions in Europe and elsewhere. At the time of the big merger, AOL/Time Warner was seen as the perfect illustration of the importance of new delivery technologies and the Internet as a driving force behind the media conglomeration tendency. It was also presented as a clear example of synergy potentials, or the tendency whereby different divisions within a media corporation develop cross-promotional activities and use their outlets to sell a common product or a recognizable brand (e.g., the exploitation of New Line Cinema’s Lord of the Rings through books, gadgets, DVDs, and merchandising within the Time Warner group). The monstrous AOL/Time Warner merger, however, did not work out completely as the corporation’s managers and observers had expected. In its first year, AOL/Time Warner faced a big loss, while the market value of AOL (and other Internet companies) decreased. In 2002, the corporation was renamed Time Warner, while many more transactions were made in an attempt to reduce the debt load.

Another dominant US-based media group, often quoted for illustrating corporate trends of cross-media synergy, internationalization, and expansion, is Viacom. The Viacom Group, which goes back to CBS, grew heavily through mergers and acquisitions from the 1970s onwards. In 2005, Viacom’s empire ranged from cable network and television to interests in the publishing, radio, video, and filmed entertainment industries. Besides the activities under the Paramount label (film library of more than 2,500 titles including Titanic, film production, distribution, film theaters, home video), Viacom is mostly associated with cable and television networks such as Showtime, the MTV chain, and CBS, as well as with television and film production companies. In March 2005, it was announced that the media conglomerate had decided to split up into two separately traded public companies. The split, which was inspired by internal rivalry between managers and shareholders and which tried to revitalize Viacom’s stagnating stock price, took effect at the end of 2005, leading to the emergence of CBS Corporation and (the new) Viacom. The latter now comprises high-growth assets, namely the cable networks (MTV in particular) and movie studios (Paramount Pictures and DreamWorks). The other company, CBS Corporation, includes the CBS and UPN broadcast TV networks, the CBS, Paramount, and other television production operations, the Simon & Schuster publishing activities, Paramount amusement parks, as well as activities in radio, digital media, and advertising. The reorganization went further after the split, with the sale of some other assets (e.g., the Paramount parks were sold in 2006).

A third major corporation is the Walt Disney Company, often quoted as one of the most synergetic players in the media and entertainment field. Founded in 1923 by the brothers Walt and Roy Disney, the small independent film production company managed to become a major with interests in many directions. Following a difficult period after Walt Disney’s death in 1966, the company struggled to survive, but since the 1980s Disney has been the driving force behind many new successful initiatives (Touchstone Pictures, the Euro Disney resort near Paris), mergers and acquisitions within the field (e.g., Miramax in 1993, Capital Cities/ABC in 1996, Pixar in 2006), and the strategic use of new technologies. The corporation, which is claimed to be valued at $32 billion, is best known for its activities in (animation) feature film production, distribution, and exhibition (e.g., Miramax, Walt Disney Pictures), record labels (Buena Vista Music Group), an empire of theme/amusement parks and resorts, as well as in cable, television, and radio network activities (ABC, ESPN, the Disney Channel). The corporation’s products are heavily marketed and circulated in other forms, such as books and interactive media (Buena Vista Games), as well as a wide range of merchandise.

The world of the big media conglomerates does not only consist of US-based corporations. A clear example is News Corporation, controlled by Australian born, but naturalized American Rupert Murdoch and his family. News Corporation, whose revenue is estimated at around $24 billion, has its roots in publishing, the newspaper industry, and television in Australia, but Murdoch soon moved to the UK and the USA. The conglomerate now controls dozens of magazines and newspapers in Australia, the UK (including leading tabloids such as the Sun, and the quality paper The Times), the USA (e.g., the New York Post), and Asia. Murdoch’s adventure in the American audiovisual industry started in 1981, when the tycoon purchased half of the Twentieth Century Fox film studio. In 1986 Murdoch launched an attack on the “big three” television networks by creating the Fox Broadcasting Company. Fox Television grew from an independent broadcaster to a much criticized, but successful, network in the USA. The Fox empire now comprises a range of thematic cable network programming in the USA (Fox News, Fox Movie Channel, etc.), where it also controls some of the leading film and television production companies (e.g., Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation). News Corporation’s television interests reach from the USA to Australia, Latin and South America, Asia, the Eurasia region, central and eastern Europe, and the UK (e.g., BSkyB). News Corporation is now one of the three largest international media groups, operating in most sectors and most continents. Besides its television, film, magazine, and newspaper activities, the corporation also has major interests in book publishing (HarperCollins), radio, music, advertising, and the Internet and interactive media.

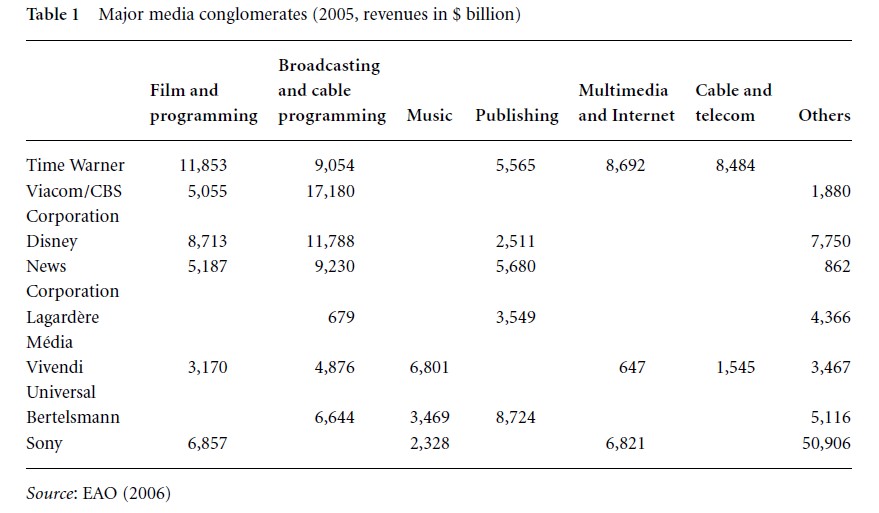

The list of major media conglomerates also contains some French-based groups, including the Lagardère Média company, which is mainly active in the press and book publishing industry (under Hachette Filipacchi Médias), the music industry and record shops (Virgin Megastores in different parts of the world), radio, television, and new media (Table 1). Another major French player with a tumultuous history is Vivendi, which is active in publishing, music, television and film, telecommunications, and the Internet, as well as video games. Vivendi, now estimated at nearly $20 billion, grew out of the French water and energy company CGE. In 1998, CGE was renamed Vivendi and began to invest in the telecommunications sector and the mass media in Europe and North Africa (e.g., the Canal+ Group). Two years later, Vivendi acquired the Canadianbased Seagram’s entertainment division. Through this acquisition, Vivendi came to control some of the most prestigious American media icons such as MCA, Universal Studios, and the Universal theme parks, as well as the PolyGram and Deutsche Grammophon record companies. However, the new Vivendi Universal conglomerate discovered that this rough acquisition and diversification strategy was not as rewarding as expected. The company started a strategy to sell nonstrategic assets. In 2004, some 80 percent of the Vivendi Universal entertainment branch was sold to General Electric’s NBC, now forming the powerful NBC Universal group, which controls a wide array of news and entertainment television networks, film and television companies, theme parks, etc. After slimming down its assets considerably and changing its name again to Vivendi in 2006, the French conglomerate is still an important player in the music industry (Universal Music Group), television, and the games and telecommunications industry, while maintaining a 20 percent part of NBC Universal.

Table 1 Major media conglomerates (2005, revenues in $ billion)

Another major conglomerate with European roots is the German-based Bertelsmann, which started as a book publisher. After World War II, Bertelsmann grew into a major German multimedia group with interests in the film, music, newspaper, and magazine industries. In the 1980s, the group started to develop a clear international strategy, acquiring American and other music labels. Ever since, the Bertelsmann group, with its revenue of nearly $18 billion, has been among the leaders in the world’s media and entertainment scene, with major interests in the publishing, music, television, and new media industries. The conglomerate consists of six divisions, including RTL (a powerful network of television channels in Europe), Gruner + Jahr (the biggest European publisher, with major interests in the USA), Random House (one of the leading publishers of popular books worldwide), Bertelsmann Music Group (BMG, a key player in the music industry), and Direct Group (a network of book clubs and other assets with a global reach).

A final player, exemplifying the corporate strategies of conglomeration, is the media and entertainment division controlled by Sony. This Japanese multinational with a leading position as a hardware manufacturer of electronics, games, videos, computers, and information technology, started to increase its interests in the media and entertainment arena at the end of the 1980s. After the acquisition of CBS Records (transformed into Sony Music Entertainment), it purchased Columbia Pictures in 1989 for $3.4 billion, using it to build the Sony Pictures Entertainment unit. In recent years Sony has been active in many more mergers and joint ventures, increasing its position in the film, television, and audiovisual scene (interests in the MGM Company) and the music industry (with BMG).

Discussion

This picture of a continuously changing world of major media conglomerates is far from complete and should pay attention to internal rivalries, as well as alliances and the position taken by other players in the field. The latter includes powerful conglomerates controlling an increasing amount of cultural production within national or even wider boundaries (e.g., the Spanish PRISA, Brazilian Globo). Referring to the extreme case of Fininvest, the holding company built around the former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, with its established market leadership in sectors ranging from commercial television and advertising to the film and publishing industries, it is clear that the issue of media conglomeration goes further than questions dealing with the structure of the media market. The case of Berlusconi exemplifies wider concerns related to the possible implications of media conglomeration.

A first bundle of wider questions deals with how far a market can be controlled without harming competition in terms of production, dissemination, and consumption of media products or content. Critical voices in the debate argue that the emergence of strong conglomerates with holdings in several media with an international scope reduces the diversity of cultural goods in circulation. From this perspective, conglomeration might have a restricting effect on media content while it tries to offer more variants of the same basic themes and images (Murdock & Golding 2005). Critics argue that media conglomerates seek content that can move fluidly across different media and channels (synergy), while they ignore creative talent and content in favor of commercial viability. Market-oriented media systems make no distinctions between people as consumers and as citizens, while the commodification tendency transforms messages into marketable products and tends to deny the free access and distribution of other content. This critical analysis is countered by arguments claiming that a free market has led to a decreasing oligopoly and the emergence of new players, while consumers enjoy more choice than ever (Compaine 2005). This position refers to the growing amount of television and other media providers since the 1980s, the emergence and the growing use of the Internet as a source for information and entertainment since the 1990s, as well as the notion of counterculture audiences who do not accept what major media conglomerates offer. The answer to this position is that a key to understanding the media conglomeration phenomenon is that major players in the field continuously try to absorb viable alternatives through mergers in order to extend their scope and consolidate their position.

A second set of questions refers to a higher level of implications, dealing with the role of the media as a central political and societal institution in democracy. Inspired by public sphere theories in relation to the media, critics of media conglomeration notice that the traditional worries about the power of press barons and media moguls in controlling the flow of information and open debate in society, have only increased since the 1980s. The case of Italy, where Berlusconi openly used his media empire to influence the political arena and public debate, is used to underline the fear that the growing power of media conglomerates might restrict information and harm democracy. Opponents claim that the danger to democracy is a myth given the extension of choice and the survival and even emergence of new alternative sources of information. Also, it is argued, managers of major media conglomerates are not “fostering a political ideology or suppressing an ideology through the media properties they program” (Compaine 2005, 46). Referring to the American debate on the role of Murdoch’s Fox Television and the absence of critical information on the Bush administration’s foreign policy, it is clear, however, that this issue remains open for debate.

References:

- Bagdikian, B. (2004). The new media monopoly. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Compaine, B. (2005). The media monopoly myth: How new competition is expanding our sources of information and entertainment. Washington, DC: New Millennium Research Council.

- EAO (2006). Yearbook 2006: Film, television and video in Europe. Strasbourg: European Audiovisual Observatory.

- McChesney, R. W. (1997). Corporate media and the threat to democracy. New York: Seven Stories.

- Murdock, G., & Golding, P. (2005). Culture, communications and political economy. In J. Curran & M. Gurevitch (eds.), Mass media and society. New York: Hodder Arnold, pp. 60 – 83.

- Tomlinson, J. (1999). Globalization and culture. Cambridge: Polity.

- Thussu, D. K. (2000). International communication. London: Arnold.

- Wasko, J. (2003). How Hollywood works. London: Sage.