One of the most oft-cited approaches to studying media effects that emerged in the early 1970s is known as the agenda-setting effect (or function) of mass media. First tested empirically in the 1968 US presidential election by University of North Carolina journalism professors Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw (McCombs & Shaw 1972), this approach originally focused on the ability of the mass media to tell the public what to think about rather than what to think. This was a sharp break from previous media effects studies that had focused on what people thought (their opinions and attitudes) and on behaviors such as voting and purchasing various goods and services.

In their original 1968 study, published in Public Opinion Quarterly in the summer of 1972, McCombs and Shaw quoted Bernard Cohen, author of The press and foreign policy, who wrote that the press “may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about” (Cohen 1963, 13). They also quoted from Kurt and Gladys Lang’s chapter on the mass media and voting in Bernard Berelson’s Reader in public opinion and communication: “The mass media force attention to certain issues. They build up public images of political figures. They are constantly presenting objects suggesting what individuals in the mass should think about, know about, have feelings about”.

To empirically test this agenda-setting effect of mass media, McCombs and Shaw content analyzed four local newspapers, the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and the NBC and CBS evening news broadcasts, and compared the rankings of the key issues by these news media with undecided voter respondents’ answers to a survey question asking them what they were most concerned about at the time (the two or three main things that they thought the government should concentrate on doing something about). This study produced some very strong correlations between the rankings of issues by the media and by the public, leading to the conclusion that the public learns not only about a given issue but also how much importance to attach to that issue from the amount of information in news reports and its position.

Since this initial study of media agenda setting, there have been several hundred studies carried out by scholars in the US and other countries such as Germany, Great Britain, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, Taiwan, and others. Most of these studies have focused on the relationship between news media ranking of issues (by amount and prominence of coverage) and public rankings of the perceived importance of these issues in various surveys, a type of research that Dearing and Rogers (1996) have called public agenda setting, to distinguish it from studies that are concerned mainly with the causes of changes in the media agenda (media agenda setting) or the impact of media agendas on public policy agendas (policy agenda setting).

The evidence from scores of such public agenda-setting studies is mixed, but on the whole it tends to support a positive correlation – and often a causal relationship – between media agendas and public agendas at the aggregate (or group) level, especially for relatively unobtrusive issues that do not directly impact the lives of the majority of the public, such as foreign policy and government scandal. At the individual level, the evidence is not as strong (McLeod et al. 1974). That is, the individual rank orders of issues are not necessarily the same as the aggregate ranking compiled from many individual answers to the question about the most important issue facing the country (or state or city or community).

Methods Of Studying Agenda Setting

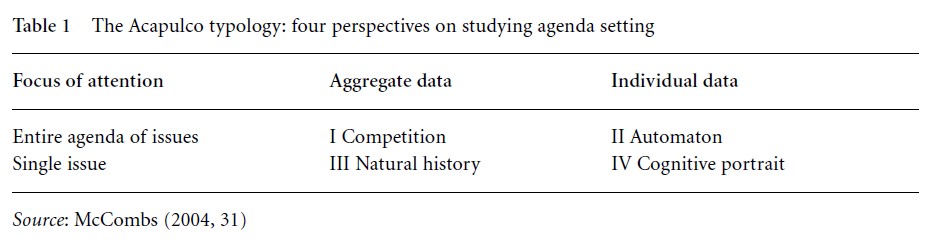

In addition to examining the relationships between media and public agendas at the aggregate and individual levels, it is also possible to study single issues over time using either aggregate (group) or individual-level data. McCombs (2004) has described these four different approaches (entire agenda, aggregate level; entire agenda, individual level; single issue, aggregate level; and single issue, individual level) in terms of a four-cell typology, which he calls the Acapulco typology because it was first presented at the annual conference of the International Communication Association (ICA) there in 1980 (Table 1).

Table 1 The Acapulco typology: four perspectives on studying agenda setting

He calls the first perspective (studying an entire agenda at the aggregate or group level) “competition” because it examines an array of issues competing for media and public attention. It was the approach used in the original 1968 Chapel Hill study, and it has been the most common approach employed in agenda-setting research since that time. It has also yielded notably stronger correlations between media and public agendas than studies using individual-level data to compare media and individual persons’ agendas (an approach that McCombs calls “automaton”). He notes that another way of thinking about this approach is in terms of the ability of the news media to mobilize a constituency among the public for a particular issue.

Probably the second most common approach to studying agenda setting has been the use of aggregate data to study media coverage and public concern about single issues over time (an approach that McCombs calls “natural history”). Using media content and aggregate public opinion data over time, it is possible to track the rise and fall of media attention to and public concern over particular issues, and to get a sense of whether increased media attention precedes, coincides with, or follows an increase in public concern – essential information for inferring a causal relationship. A seminal study using this approach is Funkhouser (1973), who correlated news media coverage of major issues during the 1960s with public opinion and real-world conditions during the decade.

It is also possible with this approach to see if the relationship between media attention and public concern over a particular is linear or nonlinear – something that has been explored in relatively few agenda-setting studies (see, for example, a chapter by William Gonzenbach and Lee McGavin on a methodological analysis of agenda setting in McCombs et al. 1997, which explores the use of time-series analysis in studying agenda setting and cites several studies employing nonlinear analysis by David Fan, Jonathan (Jian-Hua) Zhu, and Russell Neuman). This chapter suggests that the methods of nonlinear approaches can be seen in the equations and analysis of some agenda-setting studies, and that one of the most significant contributions of agenda-setting research is to take a leading role in re-examining assumptions about linear relationships.

One of the earliest and most thorough studies to do this was by Hans-Bernd Brosius and Hans Mathias Kepplinger (1992), who questioned the linearity assumption of much agenda-setting research and who proposed four nonlinear models of the relationship of media coverage and public opinion: threshold (a certain level of media attention is necessary to affect public concern); acceleration (public concern increases or decreases faster than media coverage); inertia (public concern increases or decreases at a slower rate than media coverage); and echo (unusual peaks in media coverage have long-term effects on public concern).

The third perspective or approach to studying agenda setting is to use individual-level public data to study a single issue over time. It has been called “cognitive portrait” by McCombs (2004) and is less common than the natural history approach using aggregate public data. Examples of the cognitive portrait approach include experimental studies in which the salience of a single issue for each individual person is measured before and after exposure to news programs where the amount of exposure to various issues is controlled. Shanto Iyengar has done a number of these studies (Iyengar 1979; Iyengar & Kinder 1987). Jian-Hua Zhu, in his chapter with William Boroson on a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of individual differences in McCombs et al. (1997), has also analyzed single issues over time by disaggregating public opinion data by educational and income levels, an approach that seems to fall in between the natural history and cognitive portrait approaches.

The fourth approach, called “automaton,” has been the least studied. It involves comparing entire rankings of issues for each individual person with various media rankings of issues, and typically these correlations are much lower than those found when comparing an aggregate ranking of issues with media rankings (see McLeod et al. 1974; Erbring et al. 1980). This is not surprising because it would be a return to a “hypodermic needle” or very powerful media effects model that has not received much support from empirical studies since the 1940s.

A Second Level Of Agenda Setting

In the majority of studies to date, the unit of analysis on each agenda is an object, a public issue. But objects have attributes, or characteristics. When the news media report on public issues or political candidates, they describe these objects. Due to the limited capacity of the news agenda, however, journalists can only present a few aspects of any object in the news. A few attributes are prominent and frequently mentioned, some are given passing notice, and many others are omitted. In short, news reports also present an agenda of attributes that vary considerably in salience. Similarly, when people talk about and think about these objects – public issues, political candidates, etc. – the attributes ascribed to these objects also vary considerably in their salience.

These agendas of attributes have been called “the second level” of agenda setting to distinguish them from the first level, which has traditionally focused on issues (objects), although the term “level” implies that attributes are more specific than objects, which is not necessarily true. The perspectives and frames that journalists employ draw attention to certain attributes of the objects of news coverage, as well as to the objects themselves.

Agenda Setting And Framing

Tankard et al. (1991, 3) have described a media frame as “the central organizing idea for news content that supplies a context and suggests what the issue is through the use of selection, emphasis, exclusion and elaboration.” Entman (1993, 52) argues that “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (italics in original). McCombs (1997, 37) has suggested that in the language of the second level of agenda setting, “framing is the selection of a restricted number of thematically related attributes for inclusion on the media agenda when a particular object is discussed.” He argues that there are many other agendas of attributes besides aspects of issues and traits of political candidates, and a good theoretical map is needed to bring some order to the vastly different kinds of frames discussed in various studies. This he sees as a major challenge and opportunity for agenda-setting theory in its exploration of the second level.

Not all scholars agree that second-level agenda setting is equivalent to framing, at least not to more abstract, or macro-level, framing. Gamson (1992) has conceived of framing in terms of a “signature matrix” that includes various condensing symbols (catch-phrases, tag lines, exemplars, metaphors, depictions, visual images) and reasoning devices (causes and consequences, appeals to principles or moral claims). Some would argue that secondlevel agenda setting is more similar to the first part of this matrix than to the second, because it is easier to think of condensing symbols as attributes of a given object, but more difficult to think of reasoning devices as attributes.

Nevertheless, there are similarities between second-level agenda setting and framing, even if they are not identical processes. Both are more concerned with how issues or other objects (people, groups, organizations, countries, etc.) are depicted in the media than with what issues or objects are most (or least) emphasized. Both focus on the most salient or prominent aspects or themes or descriptions of the objects of interest. Both are concerned with ways of thinking rather than objects of thinking, and with the details of the pictures in our heads rather than the broader subjects. But one primary difference between the two approaches, in addition to those mentioned above, is that second-level agenda-setting research has been more concerned with the relationship between media and audience ways of thinking than has framing research, which has concentrated more on how the media cover and present various subjects.

Agenda Setting And Priming

Several scholars have tried to link agenda-setting research with studies of “priming” that examine the effects of media agendas on public opinion as well as public concerns (McCombs et al. 1997). The focus on the consequences of agenda setting for public opinion can be traced back at least to Weaver et al. (1975, 471), who speculated in their 1972 –1973 panel study of the effects of Watergate news coverage that the media may do more than teach which issues are most important – they may also provide “the issues and topics to use in evaluating certain candidates and parties, not just during political campaigns, but also in the longer periods between campaigns.” The basic idea of priming is that by increasing the perceived salience of some issues or topics (and also their attributes), media coverage can influence the criteria or standards by which certain people or groups are evaluated.

Not all scholars agree that priming is a consequence of agenda setting, however. Some have argued that both agenda setting and priming rely on the same basic processes of information storage and retrieval, where more recent and prominent information is more accessible. Regardless of these debates, it seems likely that an increase in the salience of certain issues, and certain attributes of these issues, does have an effect, perhaps indirect, on public opinion. A recent article by Son and Weaver (2006) confirms that the media attention to a particular candidate, and selected attributes of a candidate, does influence his or her standing in the polls, cumulatively rather than immediately. And an earlier study by Weaver (1991) found that increased salience of an issue was associated with public opinion and behavior regarding the issue.

Problems And Future Directions

Toshio Takeshita (2006) has identified what he considers to be three critical problems with agenda-setting research: process, identity, and environment. The process problem focuses on the degree to which agenda setting is automatic and unthinking; the identity problem is concerned with whether second-level or attribute agenda setting will become indistinguishable from framing or traditional persuasion research; and the environment problem stems from the development of communication technology and the subsequent growth in the number of news outlets, and whether that will reduce and fragment the agenda-setting effect of media at the societal level. Takeshita (2006) suggests that future research on agenda setting should focus on the factors that distinguish “genuine” or deliberative agenda setting from “pseudo-”agenda setting that is automatic and unthinking. He also suggests focusing on how the salience of certain attributes of a given object (be it an issue or a candidate) leads to the development of attitudes toward that object.

In addition to these suggestions, it seems clear that more research is needed to clarify the similarities and differences between second-level agenda setting and framing, on the salience and perceived importance of issues and attributes, and on the conditions under which media agendas are likely to influence not only public but also policymakers’ agendas. And there needs to be more research on the influences on the media agenda from various sources. Agenda setting should be conceptualized as a societal-level process as well as an individual-level one. Not all agenda-setting processes should be analyzed at the psychological level. Some must be studied at the societal or cultural level to gain a richer understanding of how these processes occur, and the forces that shape them.

References:

- Brosius, H. B., & Kepplinger, H. M. (1992). Linear and nonlinear models of agenda-setting in television. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 36, 5 –23.

- Cohen, B. (1963). The press and foreign policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Dearing, J. W., & Rogers, E. M. (1996). Agenda-setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

- Erbring, L., Goldenberg, E. N., & Miller, A. H. (1980). Front-page news and real-world cues: A new look at agenda-setting by the media. American Journal of Political Science, 24(1), 16 – 49.

- Funkhouser, G. R. (1973). The issues of the sixties: An exploratory study of the dynamics of public opinion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(1), 62 –75.

- Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Iyengar, S. (1979). Television news and issue salience: A reexamination of the agenda-setting hypothesis. American Politics Quarterly, 7, 395 – 416.

- Iyengar, S., & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that matters: Television and American opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lang, K., & Lang, G. E. (1966). The mass media and voting. In B. Berelson & M. Janowitz (eds.), Reader in public opinion and communication, 2nd edn. New York: Free Press, pp. 455 – 472.

- McCombs, M. (1997). New frontiers in agenda setting: Agendas of attributes and frames. Mass Communication Review, 24(1, 2), 32 –52.

- McCombs, M. (2004). Setting the agenda: The mass media and public opinion. Cambridge: Polity.

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 176 –187.

- McCombs, M., Shaw, D. L., & Weaver, D. (eds.) (1997). Communication and democracy: Exploring the intellectual frontiers in agenda-setting theory. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- McLeod, J. M., Becker, L. B., & Byrnes, J. E. (1974). Another look at the agenda-setting function of the press. Communication Research, 1, 131–166.

- Son, Y. J., & Weaver, D. H. (2006). Another look at what moves public opinion: Media agenda setting and polls in the 2000 U.S. election. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(2), 174 –197.

- Takeshita, T. (2006). Current critical problems in agenda-setting research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(3), 275 –296.

- Tankard, J., Hendrickson, L., Silberman, J., Bliss, K., & Ghanem, S. (1991). Media frames: Approaches to conceptualization and measurement. Paper presented at the annual convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Boston, August 7–10.

- Weaver, D. (1991). Issue salience and public opinion: Are there consequences of agenda-setting? International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 3, 53 – 68.

- Weaver, D. H., McCombs, M. E., & Spellman, C. (1975). Watergate and the media: A case study of agenda-setting. American Politics Quarterly, 3(4), 458 – 472.

- Weaver, D., McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. L. (2004). Agenda-setting research: Issues, attributes, and influences. In L. L. Kaid (ed.), Handbook of political communication research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 257–282.