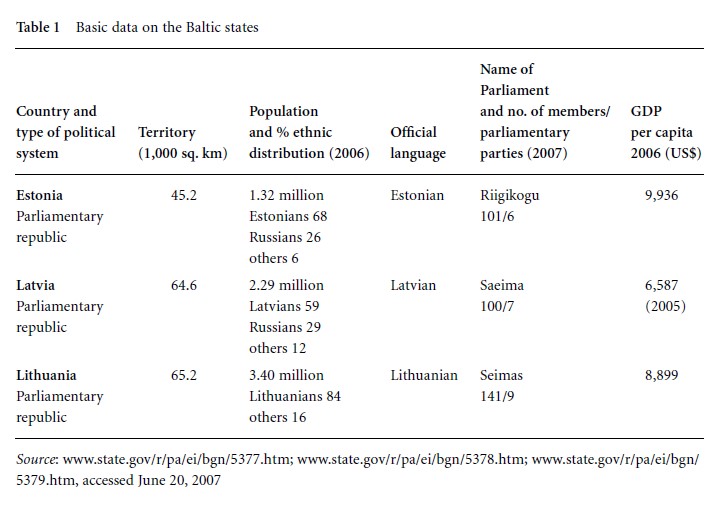

The three countries on the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea in northeast Europe – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, known collectively as the Baltic states – had been subject to the empire-building policies of neighboring countries around the Baltic Sea since the thirteenth century before they first achieved independence from 1918 to 1940. In 1939, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact brought them within the sphere of Soviet influence and they were incorporated into the Soviet Union as Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs) in 1940. Since regaining independence in 1991, the Baltic states have aligned their future with western Europe by joining both NATO and the EU in 2004. While the similarity of their historical paths and their geopolitical situation might seem to have created the conditions for a common development of their media, their ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural peculiarities have resulted in three different systems, which are among the smallest in Europe with potential audiences of 1.36 million in Estonia, 2.33 million in Latvia, and 3.46 million in Lithuania (see Table 1).

Table 1 Basic data on the Baltic states

Table 1 Basic data on the Baltic states

The press in the Baltic countries emerged in the seventeenth century in the foreign languages of the dominant members of society – the Baltic Germans in Estonia and Latvia, and the Poles in Lithuania. The first periodical publications in national languages appeared in Estonian in 1766, Latvian in 1768, and Lithuanian in 1823. Newspapers in these languages were published regularly only in the second half of the nineteenth century. When these states first gained independence after World War I, the press in each country was not restricted until the parliamentary democracies were replaced by authoritarian regimes in Lithuania in 1926, Estonia in 1934, and Latvia in 1934. Subsequently, the centralized standards of the all-Soviet media were introduced in 1940 – 1941 and from 1944 onwards.

Media Under Soviet Rule

The main goal and function of the Soviet Communist media system was propaganda in support of the power of the Communist Party elite. All the media, as well as printing, publishing and distribution facilities, were owned, supervised, and controlled by the Communist Party, and fully subsidized from the state budget. The media system in each SSR was hierarchical. The most important newspaper was the organ of the Communist Party – one national daily in each Republic’s national language and its counterpart in Russian. The next most important were the national dailies of the Communist Youth League, again in Russian and in the national languages. Locally, one Communist Party daily was allowed in each city and district, and an evening paper in the larger cities.

The most authoritative source of foreign and all-Union information was the government news agency TASS (the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union). The national news agency of each Republic was permitted to produce and distribute only news of national and local importance. Broadcasting followed a similar hierarchical structure, with the most important radio and TV channels in Moscow and national state television and radio in the SSRs.

Media In Transition

The Soviet media system in the Baltic countries had begun to collapse during the independence movements in 1988 –1990, and with the societal transition to democracy and a free market economy was entirely transformed. This process involved a transition from socialist to capitalist property structures in the media markets and the enforcement of media-related legislation. The Constitutions of all three countries guarantee the freedom of expression, the right of citizens to receive information, and the prohibition of censorship. The 2006 press freedom index of 168 countries by Reporters without Borders ranks Estonia in sixth to seventh position together with Norway, Latvia in tenth to thirteenth, and Lithuania in twenty-seventh to twenty-eighth.

There are seven main features of media development common to the Baltic states after 1990:

1 Privatization of the state-owned press. Initially, existing editorial teams privatized their publications by establishing hundreds of small joint-stock companies which were then sold to local entrepreneurs who turned them into small national companies. A consolidation of the larger national companies dominating the market led inevitably to foreign takeovers.

2 Fundamental structural changes caused by privatization and the consequent inflow of foreign media capital. This led to diversification and fragmentation of the press and broadcasting markets in the early 1990s.

3 Stabilization and increasing competition. This resulted in fairly concentrated media markets and liberal market models by 2000.

4 Total technological restructuring of newsrooms as a result of rapid technological development during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

5 Intensity of competition for limited audiences and advertising revenue has led to a high degree of commercialization, the decline of journalistic standards, and a decrease of public trust in the media.

6 Strong shift toward commercial broadcasting. This has eroded the position of public service broadcasting, the audience share of which is from 11 percent in Latvia to 18 percent in Estonia in 2007.

7 Unions of journalists have not been able to gain authority among journalists either as professional organizations or as trade unions.

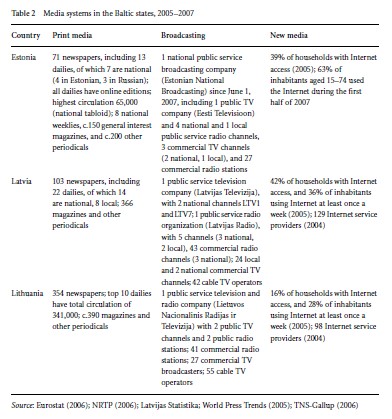

The basic structures of the media systems in the Baltic States are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Media systems in the Baltic states, 2005 –2007

Table 2 Media systems in the Baltic states, 2005 –2007

Dominant Characteristics

While there is not a common pattern of ownership among the three Baltic media systems there are three broad patterns. First, there is a dominance of Nordic media capital in the Baltic states. Eesti Meedia AS (92.7 percent owned by Norwegian Schibsted ASA) and AS Ekspress Grupp (100 percent Estonian) produce over 70 percent of newspapers and magazines in Estonia. Futhermore, through Eesti Meedia AS, Schibsted owns Kanal 2, one of the two commercial TV channels with national coverage, 34 percent of the largest commercial radio chain with six stations, and the largest and most modern printing enterprise Kroonpress. In addition to Schibsted, Nordic holdings in Estonia include Bonnier AB (Swedish), Egmont Holding International AS (Danish), and Alma Media (Finnish).

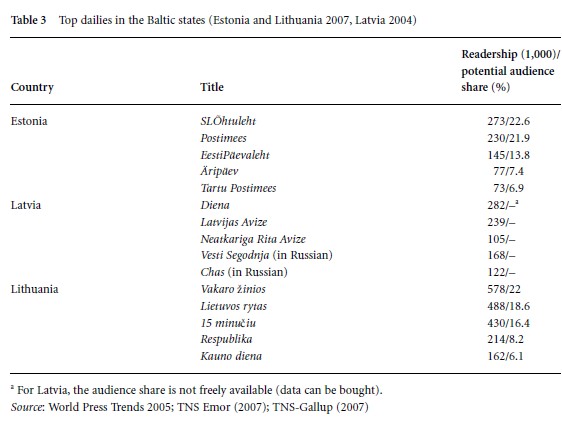

The Latvian press market is split between two major publishing groups. Latvia’s largest oil transit company Ventspils Nafta has shares in several print and publishing companies and owns the third largest daily Neatkariga Rita Avize. The Swedish Bonnier Group, through its 63 percent holding in AS Diena, controls the largest national daily Diena (readership of around 300,000), 11 regional newspapers, and seven magazines, distribution and subscription services, and printing facilities. Table 3 shows the top dailies in the Baltic states, with their readership and potential audience share.

Table 3 Top dailies in the Baltic states (Estonia and Lithuania 2007, Latvia 2004)

Table 3 Top dailies in the Baltic states (Estonia and Lithuania 2007, Latvia 2004)

Second, the Lithuanian press market is still dominated by three national firms, Lietuvos Rytas UAB, Respublikos Leidiniu Grupe, and Achemos Grupe. Nordic capital entered the market in the spring of 2006 through the purchase of the largest regional daily Kauno diena by the Norwegian Orkla Media.

Third, there is trans-national ownership of regional networks. The Baltic News Service (BNS), the largest information agency in the region, is owned by Alma Media (Finnish); the online news portal Delfi (with its Russian language counterparts in Estonia and Latvia) is owned by Findexa (Norwegian), the Scandinavian–Baltic television network TV3 (with the channels in all Baltic countries) is owned by Modern Times Group (Swedish), and Bonnier (Swedish) owns the business newspaper Dagens Industri, which is edited and produced by local offices in all three countries.

Regulations that would restrict foreign ownership rights or cross-media ownership do not exist in the Baltic region, neither is there special legislation to support media diversity and pluralism. Competition legislation applies to the media sector for the provision of the conditions that insure free-market competition. There are also a few provisions in the other laws and broadcasting regulations that prohibit monopoly. Broadcasters in Latvia, except for public broadcasters, may not have more than three programs. A political party or a commercial entity that is controlled by a political party may not own a radio or television station.

Radio And Television

All three countries have adopted laws that regulate broadcasting and advertising which are aligned with the EU “Television without Frontiers” directive (1989/1997). The general principles and rules of this directive incorporated by each country’s laws concern the European works quota, the rules on the content and permissible amount of the daily and hourly advertising time, the use of exclusive rights, and the broadcasting of events of major importance to the public, and the right of reply. These principles also require advertising to be distinguishable from other program content, a ban on tobacco advertising, surreptitious advertising, and advertising that works against the interests of children. All countries have passed advertising laws that also apply to the mass media. More general mass media laws exist only in Latvia and Lithuania.

The Lithuanian Law on Provision of Information to the Public (adopted as Mass Media Law in 1996, and amended in 2000) regulates the functioning of all mass media and lays down the obligations and liabilities of journalists, public information producers, and disseminators (who must be registered in the Register of Enterprises). Every broadcaster in Lithuania must obtain a license from the Radio and Television Commission, an independent institution for the regulation and supervision of the activities of radio and television broadcasters, and is accountable to Parliament. The Commission consists of 12 members, one of whom is appointed by the President, three by Parliament, and the remaining eight by professional organizations (architects, journalists, composers, writers, cinematographers, artists, actors, and periodical press publishers). The Law on the National Radio and Television provides specific regulations for the funding, administration, and functioning of the National Radio and Television and the legal basis for the formation of the Lithuanian Radio and Television Council, which functions as the highest governing body for the organization. The Council consists of 12 members who are prominent individuals in the social, scientific, and cultural spheres (of whom four are appointed by the President and four by Parliament). Lithuanian National Radio and Television belongs to the state and is 75 percent funded by the government.

The Latvian Law on Radio and Television (adopted 1995, amended in 2001) regulates both private and public broadcasters, as did the Estonian Broadcasting Act (adopted in 1994, amended in 2001, 2004) until June 2007. Then the Estonian Parliament adopted the National Broadcasting Act, according to which the public broadcasters Estonian Television and Estonian Radio will be merged into one organization: Estonian National Broadcasting (ENB). The supervisory body for ENB will be the Estonian Broadcasting Council, which is accountable to Parliament and financed by the government. The Council consists of nine members, five of whom are appointed by Parliament from among MPs in accordance with political balance, and four from among recognized specialists in the fields related to public broadcasting functions.

The Latvian Law on Press and Other Mass Media (adopted in 1990, revised in 1998) states that all mass media are subject to preliminary registration at the Ministry of Justice and that the right of establishing and publishing of mass media belongs only to legal persons and legally capable natural citizens. The Law explicitly prohibits monopolization of any kind of mass media as well as censorship. The Latvian National Radio and Television Council is granted broad powers ranging from the definition of broadcasting policies to the granting and withdrawal of licenses. It appoints the directors and board members of the Latvian National Radio and Television and also deals with viewer complaints. It comprises nine members appointed by Parliament, who must be Latvian citizens and well known to the public. No more than three members can belong to the same political party. The Council is financed by the state.

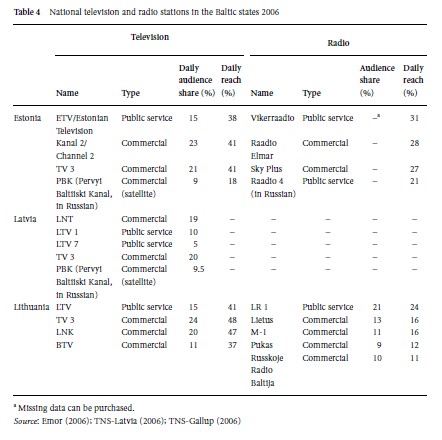

Table 4 National television and radio stations in the Baltic states 2006

Table 4 National television and radio stations in the Baltic states 2006

Table 4 shows the national television and radio stations in the Baltic states.

References:

- Bærug, Richard (ed.) (2005). The Baltic media world. Riga: Flera.

- Balcytiene, A., & Lauk, E. (2005). Media transformations: The post-transition lessons in Lithuania and Estonia. Informacijos Mokslai [Information Sciences], 33, 96 –109.

- Emor (2006). At www.emor.ee, accessed October 1, 2006. Eurostat (2006). At http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu.

- Høyer, Svennik, Lauk, Epp, & Vihalemm, Peeter (eds.) (1993). Towards a civic society: The Baltic media’s long road to freedom. Tartu: Baltic Association for Media Research/Nota Baltica.

- Internationales Handbuch Medien (2004/2005). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Latvijas Statistika. At www.csb.gov.lv.

- NRTP (2006). At www.nrtp.lv, accessed September 13, 2006.

- Strausa, S. (2004). Media system in Latvia for the study on co-regulation measures in the media sector. European Commission, DG EAC 03/04. At www.hans-bredow-institut.de/forschung/ recht/co-reg/reports/1/Latvia.pdf

- TNS-Gallup (2006). At www.tns-gallup.lt, accessed October 1, 2006.

- TNS-Latvia (2006). At www.tns.lv/?lang=en, accessed June 20, 2007.

- Vihalemm, Peeter (ed.) (2002). Baltic media in transition. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

- World Press Trends (2005).