Communication scholars, psychologists, sociologists, and other social scientists have long been interested in how individuals interpret the real world around them. Although some of the information we receive in our daily lives is first-hand, much of what we know about our communities, states, countries, and the world comes to us through second-hand sources. Perceptions of reality, rather than actual observations of reality, guide human beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. These perceptions often are solidified into normative versions of what “ought” to be. Because there are often concrete expectations of reality in one’s mind, the effects from this perceived view of the world can be just as real as effects of actually experiencing that reality. Importantly, social perceptions arise through processes of communication, resulting in a social world that appears comparable to the physical world that surrounds us. Misperceptions of reality can produce a distorted version of the real world, and it is these misperceptions that have been the focus of much attention in public opinion and communication research.

Understanding Social Reality Perceptions And Effects

Perceptions of reality, or social reality, can be conceptualized as an individual’s conception of the world (Hawkins & Pingree 1982). What intrigues many social scientists is the exploration of the specifics of these perceptions and the ways in which they are developed. As Lewin suggested, reality is not an absolute; it differs depending on an individual’s social surroundings and perceptions of those surroundings (Lewin & Grabbe 1945). Social perception has been considered from both individual and social-level perspectives. Scholars investigating perceptions at the individual level rely heavily on the works of John Dewey, Charles Horton Cooley, and George Herbert Mead, while those considering the social level draw from Paul F. Lazarsfeld, Elihu Katz, and Theodore M. Newcomb.

The individual-level conception of social reality – or, as McLeod and Chaffee (1972), refer to it, social reality – derives from Cooley’s, and later Mead’s, conceptualization of society: an affair of consciousness that is necessarily social (Mead 1930). This definition suggests that others exist in one’s mind as imaginations, and it is only in these imaginations that others have an effect on the individual. Cooley (1902) referred to these imaginations as the “solid facts” of society. Dewey’s work concerning social perception emphasized the importance of bringing the social world into studies of human behavior and cognition. He suggested that instincts, such as fear and sexual desire, are necessary but not sufficient explanations for human behavior. Any instinctual impulse, he argued, is potentially influenced by its social surroundings.

Importantly, these early scholarly works defined communication as a central mechanism through which humans exist and develop. In this sense, the mind itself arises through communication (Mead 1930). Because individuals are not capable of experiencing all reality through direct observation or physical experience, they must rely on communication with others or experience this “reality” through the mass media. Since individuals’ communication experiences differ, their “cognitive maps” (McLeod & Chaffee 1972) also will differ. In this way, individuals view their own social reality as self-evident and factual. As a result, researchers cannot easily identify which components of one’s social reality are based upon direct observation and which are based upon social learning.

The second perspective of social reality (McLeod & Chaffee 1972) defines the social system as the unit of analysis. Scholars exploring social reality from a social-system perspective focus on understanding commonly held perceptions shared in society. They often base their exploration on individuals’ perceptions of what others think, or whether an individual believes that an opinion or attitude is shared by others. When individuals perceive that others share their own views of the world, the opinion or attitude can become “real” in that particular group, community, or society. Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955) suggested that individuals obtain information from their social environment, observe whether others agree with that information, and then assume that is the “reality”.

Research on social reality has tended to focus on degrees of consensus or agreement among members of a system. This literature often draws from work in social psychology on normative sanctions (Newcomb et al. 1965). These sanctions are rules that specify which individuals are supposed to act in which ways in a society. How individuals are to be rewarded or punished depends on whether they abide by those sanctions. Current research in this area is driven by two main theses: (1) the behavior of individuals is affected systematically by various forms of social influence, and (2) this influence is embedded within a particular context. What differentiates this approach from the focus on social reality is the emphasis on groups and situations rather than individuals.

Because the media, in particular, provide individuals with indirect representations of reality, communication scholars have been particularly interested in how individuals develop cognitions of social reality based upon their use of and attention to the media. As noted earlier, much of the information we receive comes from other people and the mass media. McLeod and Chaffee (1972) noted that these sources seem no less valid than direct observation because a large proportion of this information is shared by others around us. In this sense, individuals find themselves thinking that everyone ought to see things the way they do, a normative sharing of “oughtness” that defines social reality.

Table 1 Causal mechanisms of the perceptions and misperceptions of social reality

Table 1 Causal mechanisms of the perceptions and misperceptions of social reality

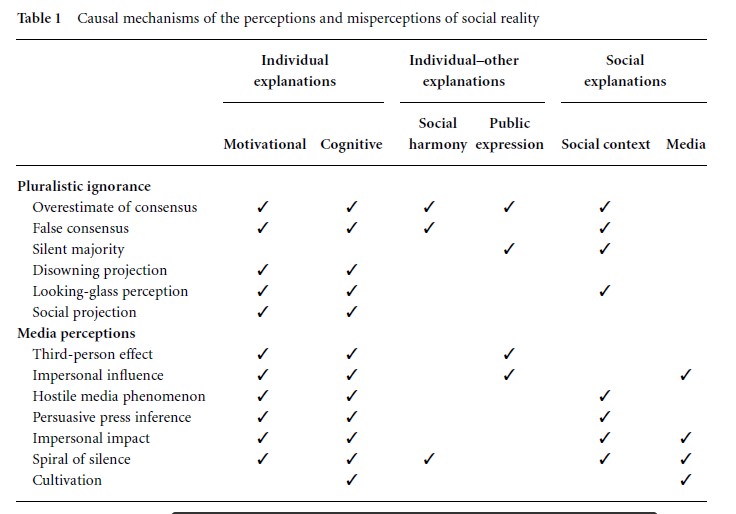

There are a number of effects associated with perceptions of social reality. One category of effects draws heavily from those effects outlined in the social psychology literature, without reference to the media in particular. These phenomena describe perceptions and misperceptions of some generalized other. The second category, outlined later, focuses on media effects in particular. Finally, the mechanisms driving these effects are described and outlined in Table 1.

General Perception Effects

Several phenomena describing perceptions (and misperceptions) of social reality have been outlined in the literature. These effects are pluralistic ignorance, overestimate of consensus, false consensus, silent majority or false idiosyncrasy effect, disowning projection, conservative and liberal biases, looking-glass perception, and social projection.

The term pluralistic ignorance is often used as an umbrella to describe all misperceptions of others’ opinions (Fields & Schumann 1976; O’Gorman & Garry 1976; Eveland 2002). Research in this area is primarily concerned with the factors that lead to individuals being more or less accurate about reality, focusing on the discrepancy between individual perceptions and actual reality. Pluralistic ignorance is most likely to occur when people have differing opinions on a divisive issue, but also results from individual factors such as fear of embarrassment, social desirability, or social inhibition. The primary assumption underlying this and other misperceptions is that individuals have a “quasi-statistical sense,” which suggests that people infer public opinion from their own intuitive sense of their environment, even without access to specific public opinion information (Noelle-Neumann 1993).

Consensus is the core concept of several social reality phenomena. Consensus occurs when homogeneous opinions exist across a group of individuals. Complete consensus on an issue exists where there is reciprocal understanding among the members of a group concerning some issue. Importantly, this concept makes no provision for individual perceptions of agreement; it simply describes a state of affairs. In and of itself, consensus does not refer to social reality. However, some research has extended this concept and suggested that an overestimate of consensus occurs when individuals perceive greater consensus on their own opinion than exists in reality. In this way, overestimation of consensus is “absolute” because it is objectively false (Eveland 2002).

The concept of false consensus, originally developed by Ross et al. (1977), describes the perception among group members about others in their group or those to whom they have similar attributes. Specifically, this concept refers to the individual tendency to see one’s own behaviors and opinions as normal and those of others as deviant or inappropriate. This phenomenon is best described as the exaggeration of the prominence of one’s own opinions. It differs from overestimation of consensus in that it is a misperception that is relative to others, rather than a misperception of reality. Hypothesis tests have consistently demonstrated this effect to be highly statistically significant with a moderate effect size (Mullen et al. 1985).

The silent majority or false idiosyncrasy effect is a specific instance in which the majority group perceives its position as the minority. This phenomenon occurs when some individuals support a position on an issue vocally and prominently, while those opposed to the issue – even if they are in the majority – remain silent. The result is that the vocal position is incorrectly perceived as the predominant one, while the silent position is incorrectly perceived as the minority. As such, the misperception is an outcome of an overestimation of the pervasiveness of the vocal opinion (Korte 1972).

The disowning projection refers to the tendency toward attributing selfish motives, evil intent, or ignorance to others and denying these characteristics of oneself (Cameron 1947). This is comparable to the social desirability effect in survey research: individuals may perceive there is a “right” answer to a question and therefore attribute “wrong” behaviors, attitudes, or opinions to others.

Conservative and liberal biases have also been documented in public opinion literature (e.g., Fields & Schumann 1976). However, Glynn et al. (1995) argue that, depending upon which phenomenon is being tested, these ideological biases could be described as false consensus or pluralistic ignorance. Moreover, these biases serve more as descriptive patterns occurring in the data, rather than concepts in and of themselves.

The looking-glass perception occurs when people see others as holding the same view as they themselves hold. The looking-glass perception is different from the false consensus effect because a divisive issue is not a precondition for the phenomenon to occur. Moreover, the perception is not by definition inaccurate but could be an accurate reflection of reality. Importantly, this phenomenon occurs quite separately from any actual distribution of opinions or attitudes in reality. The looking-glass perception is likely to arise for noncontroversial issues when people do not care much about the issue or even if there is almost universal agreement (Glynn et al. 1995).

Social projection is generally defined as the psychological phenomenon that drives each of these inaccurate perceptions. Broadly, this concept refers to individuals’ reference to self-reactions in order to describe others. Some research has suggested that social projection can actually increase individuals’ accuracy about others’ views, which counters findings on the false-consensus effect. That is, more projection, rather than less, can lead individuals to have more accurate perceptions of the social environment around them (Jones 2004). The phenomenon is quite robust and generates moderate to large effect sizes (Mullen et al. 1985; Robbins & Krueger 2005).

Media-Specific Perception Effects

Although each of the effects described above can result from perceptions or misperceptions of media content, they do not refer to the media in any consistent way. In fact, some of the effects predate mass media as we now know it. As a result, a second way of understanding perceptions of social reality has developed in response to the advent of media and mass communication research. Eveland (2002) divides these media-specific perceptions of social reality into two categories. The first covers perceptions of media content or impact, while the second maintains perceptions of social reality as the effect, but defines mass media as the primary causal mechanism.

Perceptions Of Media Content Or Impact

This category of media-specific perception effects focuses on individuals’ perceptions about media content or its influence on others. The third-person effect and impersonal influence emphasize that individuals do indeed have perceptions about media’s impact on others. Those phenomena specific to media content (the hostile media phenomenon and persuasive press inference) focus on individuals’ perceptions that the media are biased or slanted in some direction.

The third-person effect predicts that individuals exposed to a persuasive message will perceive greater effects on others than on themselves. The term was coined by Davison (1981), who based the proposition on personal experiences with journalists who were convinced that editorials had an effect on others’ attitudes, but not on people like themselves. The effect has since been delineated into two components: perceptual and behavioral. The former describes the perception alone; the latter builds on the perceptual component and suggests that the biased third-person perceptions will result in some behavioral action. The most commonly studied behavioral outcomes are support for censorship and willingness to speak out.

Impersonal influence describes the influence derived from anonymous others’ attitudes, experiences, and beliefs (Mutz 1998). From this perspective, media do not need to be universally consonant or even personally persuasive in order to impact individuals’ perceptions of media influence. The underlying assumption of this phenomenon is that the number of indirect associations among individuals has increased while direct associations have decreased. Moreover, there has been a tendency among the general public, as well as policymakers, to attribute much power to the media, which results in real consequences, even if the media’s influence has been overrated. As with the third-person effect, impersonal influence includes both the perceptual component and a behavioral component. This behavioral component is enhanced by the indirect nature of individuals’ interaction with the political world. The outcome of impersonal influence is perceptions of collective conditions obtained through the media that in turn influence individuals’ own attitudes and behaviors.

The hostile media phenomenon suggests that partisans see news media coverage of controversial events as portraying a biased slant, even in news coverage that most nonpartisans label as unbiased. An underlying assumption of this phenomenon is that media coverage is essentially unbiased. However, the seminal work on the hostile media phenomenon relied upon highly involved partisan subjects (Vallone et al. 1985). Not all scholars agree on the assumptions proposed by Vallone et al. (1985), and Gunther and Chia (2001) have suggested that the “relative hostile media phenomenon” is a broader conceptualization that does not require neutral news coverage or highly involved partisans.

The persuasive press inference hypothesis draws from the hostile media phenomenon and third-person effect and places the effects into one process. Specifically, this theory assumes that individuals (1) scan the media environment for issues of interest, (2) form impressions about the valence of media coverage, (3) infer that the news resembles what they have personally observed, (4) conclude that this media coverage influences others, and (5) perceive public opinion as corresponding to the perceived news slant (Gunther 1998). As a result of this process, people overestimate the impact of news coverage on public opinion and because of this misperception, estimates of public opinion are inaccurate. Perceived news slant, which draws from the hostile-bias phenomenon, acts as a mediating variable in the process (Gunther & Chia 2001). Although the media have indirect influence in this process, Gunther argues that these perceptions can ultimately have a self-fulfilling effect because individuals assume that the media influence those around them (Gunther 1998; Gunther & Storey 2003).

Perceptions Of Social Reality With Media As The Primary Causal Mechanism

Other research on perceptions of social reality has emphasized mass media as the primary causal mechanism explaining perceptions of social reality. Impersonal impact, spiral of silence, and cultivation are the principal theories associated with this category.

Because few people have direct personal experience with politics, mediated information has the ability to influence individuals’ perceptions of social reality at the collective level. That is, media enhance the salience of social-level judgments in addition to influencing perceptions of public opinion. This is called impersonal impact. This phenomenon historically resided in social psychology, where Tyler and Cook (1984) distinguished between two levels of judgment: personal (beliefs about one’s own conditions and risks) and societal (beliefs about conditions of the larger community). A prominent finding in related research is that the media affect societal level judgments rather than personal ones. Research has suggested that these effects are conditional, with media impact operating differently for various issues and individuals.

The spiral of silence theory is perhaps the most popular – and critiqued – theory on perceptions of public opinion. At the heart of this theory is the idea that because the climate of opinion is always vacillating, individuals are always uncertain about the opinions around them. Thus, people turn to the media to understand the climate of opinion. However, Noelle-Neumann argues that the media present biased viewpoints in a uniform way. The result of this biased news media content is that individuals perceive a majority perspective, and this perception either promotes or prevents them from speaking out. The perception of public support for a position increases individuals’ confidence in the legitimacy and strength of that position. In turn, this perception fuels their comfort in expressing that position in a public setting. The opposite effect occurs if individuals perceive themselves to be in the minority, judging a position as receiving little public support and legitimacy. Noelle-Neumann draws heavily from research in social psychology – particularly that of Solomon Asch – to support her hypothesis that people will conform to group pressure.

Cultivation implies that, over time, people are influenced by the content on television so that their perceptions of reality come to reflect those presented on television. Cultivation research is rooted in the work of George Gerbner and colleagues, whose Cultural Indicators project has generated both public and academic debate (Gerbner & Gross 1976; Gerbner et al. 1978). This theory purports that media content, which has been systematically studied for decades, displays distorted estimates of social reality. Among these distortions are the rates of crime and violence; estimates about personal risk of crime and violence; estimates of like risks from lightning, flooding, and terror attacks; estimates about the number of people who serve as police officers or lawyers; and estimates of the number of elderly, among other distortions.

Cultivation effects are commonly delineated into first-order and second-order effects (Hawkins & Pingree 1982). First-order effects refer to the correlations between television viewing and distorted estimates of social reality. Second-order effects refer to individuals’ perceptions of a mean and scary world as a result of these distortions. First-order effects have found much support, while second-order effects remain in doubt. Research has also demonstrated a weak relationship between first-order and second-order effects, suggesting that the social relevance of first-order effects is still unclear.

Two modifications have been made to the original cultivation theory. First is the concept of “mainstreaming.” This concept suggests that individuals’ own experiences can moderate the cultivation effect. In particular, those whose experiences are more discrepant from television’s representation of the world are more susceptible to cultivation effects. The second modification is the moderating effect of “resonance.” Resonance predicts an interaction between television viewing and individual experience, such that those whose life experiences are more congruent with the television world are most susceptible to cultivation effects. In this sense, mainstreaming and resonance can be viewed as competing hypotheses that occur when certain conditions are fulfilled (Shrum & Bischak 2001).

Causal Mechanisms For Social Reality Perceptions And Misperceptions

The previous section and extant literature suggest that the impersonal impact, spiral of silence, and cultivation hypotheses label the media as a primary mechanism for affecting individual perceptions of social reality. However, the perception effects described here can be attributed to one or more other causal mechanisms, including individual cognitions and motivations, social harmony and public expression norms, and social context, as well as the media. Each of these six mechanisms can be categorized under three broader categories: individual, individual–other, and social explanations. By linking each of the social reality perceptions with their corresponding causal mechanisms, one can better understand how these perceptions operate in a mass-mediated world. Importantly, these explanations are not mutually exclusive; that is, one or more mechanisms might be at work for each concept, theory, or approach. Table 1 outlines the social reality perception effects and the individual, individual–other, or social explanations that can be applied to each.

Individual Explanations

This category of causal mechanisms includes individual motivations and cognitions that lead to perceptions or misperceptions of social and media reality. Nearly all of the theories, concepts, and approaches outlined here can be attributed to either motivational or cognitive mechanisms, or both (see Table 1).

Motivational Mechanisms

Some individuals may be motivated to interpret their surroundings in a biased way because of a need for social support and validation, or a desire for self-enhancement. One example of this motivational mechanism is the phenomenon of social projection. When a need for social connectedness is made salient, individuals might interpret their surroundings in a biased way.

In other cases, individuals might be driven to see themselves as either unique from others or sharing common views, depending on the context. Prentice and Miller (1993) label this phenomenon “impression management” and suggest it is a self-serving bias that drives individuals to misperceive their surroundings. In this way, some people are motivated to maintain control over their environment (the effectance motivation). Additionally, people are often motivated to believe that unfortunate events are more likely to happen to others rather than to themselves (unrealistic optimism). Finally, ego defensiveness is a motivation that protects one’s self-concept from counterattitudinal or threatening messages. All of these motivations serve as important causal mechanisms in the third-person effect.

The false consensus effect also is based primarily on motivational mechanisms. For instance, individuals may be motivated to see similarity between themselves and what they perceive as an attractive or desirable group or person. In this case, individuals are driven by a desire for self-enhancement. Additionally, individuals with stronger needs to justify or support their own views or behavior may display false consensus because of a need for social support and validation.

The impersonal influence hypothesis can be explained by several mechanisms, but research has suggested that a primary mechanism is the “bandwagon motivation” (Mutz 1998). This occurs when individuals are motivated to affiliate with a winning team or candidate in order to enhance their own public image in the eyes of others. The thirdperson effect can also be explained in part by motivations.

Motivational explanations can also be applied to those theories that claim media as the primary causal mechanism. For instance, Noelle-Neumann cites fear of isolation, or a motivation not to be in the minority, as a driving force behind the spiral of silence. The underlying assumption of this mechanism is that people keep their opinions silent when they feel marginalized. Taylor (1982) and Hayes et al. (2005), however, have provided alternative motivational mechanisms to this fear of isolation. Taylor suggested that individuals examine the incentives and benefits of speaking out in certain circumstances, while Hayes and colleagues found that the willingness to self-censor can predict willingness to speak out.

Importantly, motivational mechanisms are not necessarily conscious or intentional. For example, one study suggests that individuals who are more prone to feelings of fear are subconsciously motivated to overestimate the prevalence of fear among their peers in order to feel more comfortable (Suls & Wan 1987).

Cognitive Mechanisms

Cognitive mechanisms are perhaps the most common explanations for social reality and media perceptions. Outcomes described in this category tend to rely on the rich literature in information processing. One possible mechanism in this category of cognitive explanations is the accessibility bias, or the tendency to derive estimates of others’ views based upon that information that is most accessible in one’s memory. Social projection has often been explained by this accessibility bias, in addition to motivational mechanisms (see Table 1).

A related mechanism is the availability heuristic, which describes the tendency to use the ease with which something is recalled as a representation of that thing’s probability (Mullen et al. 1985). This heuristic might explain false consensus effects when experimental subjects are asked to consider opposing points of view (as is the case in many experiments testing these effects). Additionally, unintentional selective exposure, attention, and retention can be defined as cognitive explanations for perceptions of social reality. For instance, individuals are likely to expose themselves to information that is agreeable to their position, attend to it, and recall it later, explaining the false-consensus effect (Sherman et al. 1984).

The hostile media phenomenon and third-person effect are each in part based on cognitive mechanisms. For instance, partisans on different sides of an issue might process the same media content, but in very different ways. They might recall information that was most hostile to their own opinions, explaining the hostile media phenomenon in some cases. A cognitive explanation for third-person effects draws from attribution theory, suggesting that people have an innate – albeit naïve – need to explain their social world. In turn, when it comes to the media, individuals adhere to a simple “magic bullet” explanation of media effects, assuming that others are easily influenced by media content.

The third-person effect also is explained by cognitive “errors.” The actor–observer attributional error occurs when individuals underestimate the extent to which others account for situational factors, and overestimate their own attention to these factors. In this way, people see themselves as more cognizant of media influence and others as easily manipulated. A second cognitive error explanation of the third-person effect is that people project negative effects onto others in order to avoid the discomfort caused by admitting that such content affects themselves. This explanation suggests that although individuals may perceive themselves as also susceptible to media effects, they push these concerns out of mind by attributing them to others.

The persuasive press inference also can be explained by individual cognitions. Research suggests that people are likely to think that their own sample of news media coverage is similar to what others see. This cognitive mechanism is based upon the law of small numbers bias, in which such a sample of news content is considered similar to the population. Additionally, impersonal influence draws from cognitive explanations. Specifically, the “cognitive response mechanism” proposes that individuals might shift their attitudes upon learning the opinions of others, because knowing these opinions encourages them to think about arguments that might explain those opinions.

Cognitive mechanisms also apply to those theories that claim media as a primary causal mechanism. For example, some scholars have proposed that cognitive mechanisms may be better explanations for cultivation effects – particularly for heavy viewers of television. Hawkins and Pingree (1982) suggested that people actively learn facts from television and in turn construct judgments about the real world based on these facts. Alternatively, Shrum and O’Guinn (1993) asserted that relevant information is more accessible and, as a result, overestimates of frequency or probability can be explained by the accessibility bias. The outcome of such heuristic processing is that media play a larger role in judgments about social phenomena with which subjects have less direct experience.

Individual–Other Explanations

Some individuals might be motivated to perceive social reality in certain ways that benefit their social interactions with others, or they might feel pressure to publicly misrepresent their opinions in order to comply with the pressures and norms of social interactions. These mechanisms can be defined as social harmony and public expression mechanisms (see Table 1).

Social Harmony Mechanism

Because conflict is not palatable to many people, there may exist motivation to see others’ positions on issues as more like their own in order to avoid argument or dissonance. Although this explanation can be considered a motivation, it specifically pertains to the anticipated future interaction with others. Therefore it is categorized separately from the above-mentioned individual motivations.

One example of the social harmony mechanism at work applies to both the falseconsensus effect and the spiral of silence. The divisiveness of some issues might influence whether individuals choose to speak their opinions in social interactions. In such an instance, the motivation to maintain accord with others in the future might overrule truthful expression of opinions. Similarly, if individuals expect to interact with other people in the near future, they may be motivated to view others as more like themselves so that the interaction is more agreeable.

Public Expression Mechanisms

Misperceptions of social reality at the individual–other level also can arise from either intentional or unintentional misrepresentation of one’s opinions in public. Prentice and Miller (1993) proposed two explanations to address both intentional and unintentional misrepresentations. The differential interpretation hypothesis describes a conscious decision to publicly misrepresent one’s opinion. The differential encoding hypothesis does not assume intentional misrepresentation, but suggests that some individuals suffer from an “illusion of transparency,” mistakenly believing that their own and others’ opinions are accurately expressed publicly.

One example of this mechanism applies to the impersonal-influence hypothesis and third-person effect (see Table 1). For instance, an individual voter might desire to influence the outcome of an election through strategic or tactical influence. This voter might assume that the media have greater influence on others than on himself or herself. In turn, the voter might publicly express preference for one candidate over another in order to counter that media influence. Such misleading public expression can clearly lead to misperceptions of social reality.

Social Explanations

The social explanations described below and outlined in Table 1 are based upon what McLeod and Chaffee (1972) referred to as social reality. That is, a context or situation serves as the causal mechanism underlying individual perceptions of social reality.

The social context of the issue – or the distribution of opinions on either side of a public debate – can serve to create misperceptions of social reality. If an issue is particularly divisive, for example, individuals are prone to the false-consensus effect because they see one side as more similar to themselves and the other side as deviant or uncommon. Alternatively, if the issue is not particularly divisive and there is general agreement, one might be prone to the looking-glass perception and exclude alternative perspectives on the issue.

The literature on mass communication and perceptions of social reality has given increased attention to media as causal mechanisms. One way to define media as a causal mechanism comes from the spiral of silence theory, which purports that the news media present viewpoints that are consistently biased toward the majority. Noelle-Neumann (1993) suggests that because these biased media messages are consonant, cumulative, and ubiquitous, they have widespread impact on those in the minority. According to the theory, mass media serve as agents of social control through which information about societal norms is conveyed. It is noteworthy that this media mechanism is not based on any specific content, but on a general assumption about media favorability toward the majority.

An additional way of defining media as a causal mechanism is through an understanding of journalistic content and professional norms. The news media apply different journalistic approaches to presenting information about opinion distributions and social reality in general. For example, content analyses have found that social reality is represented in the media through base-rate information, exemplification, or a combination of both. Base-rate information is the use of statistics and factual information to describe public opinion or social reality. Exemplification, or the use of “exemplars,” relies on personal examples and interviews. Although base-rate information tends to be more accurate in that it represents a larger portion of the population, news audiences attend to and recall social reality perceptions more often from exemplars. This suggests that the content of media predicts when and how the media influence perceptions of public opinion, and is consistent with the predictions in the persuasive press inference. This mechanism is also closely tied with cognitive mechanisms, in that exemplars are said to have superior accessibility, and thus greater impacts on perceptions of social reality.

A final way of defining this media mechanism is specific to cultivation. In cultivation studies, television content has been found to overestimate the amount of crime and violence that exists in the real world. Television content also misrepresents the proportions of blacks, Hispanics, and Asian-Americans, and the elderly. As a result, specific media content – rather than the consonant, cumulative, and ubiquitous media of the spiral of silence theory – influences perceptions of social reality over time.

Implications Of Social Reality Perceptions For Communication Research: Behavioral Outcomes

Although many scholars will contend that perceptions are in and of themselves important outcome variables, others have suggested that a link between these perceptions and individual behavior is necessary in order to establish the social relevance of such research. In this vein, several areas of research have established behavioral effects that result from social reality perceptions.

First, the third-person effect has received much support not only in its perceptual component, but also in its behavioral component. Specifically, research has found that misperceptions of media influence are related to greater support for censorship (Eveland 2002). Second, studies of pluralistic ignorance have demonstrated that misperceptions of social reality are associated with individual behavior. For example, Prentice and Miller (1993) found that misperceptions of alcohol use on a college campus positively predicted drinking behavior. This effect has been replicated with other risky behaviors such as tobacco use and marijuana use, as well as risk judgments. Third, perceptions of opinion climates are related to opinion expression, as hypothesized by the spiral of silence, although support for this relationship is weak. These perceptions have also been related to forms of political participation.

Reconstructing Social Reality

It is important to note that social reality is not a finite reification. Instead, it is a dynamic construct that can change over time and across individuals. McLeod and Chaffee (1972) outlined several ways in which social reality can be reconstructed.

Individuals are able, and likely, to move from one social reality to another at some point in their lifetime. This shift can occur when there are systematic changes in an individual’s social reality, such as a change in his or her reference groups. Such changes also can take place at critical junctures in the life course – college, marriage, children, for example – that encourage the individual to rethink or actually modify their social reality. These changes might be likely to occur in crisis situations, when individuals are more motivated to communicate effectively and seek out unambiguous information. Changes in the structure of an individual’s communication patterns also can reconstruct one’s social reality. When people communicate with different or unusual others, or pay attention to different media sources, their perceptions of social reality are likely to change.

It appears that social reality is best conceptualized as a dynamic process with both perceptual and behavioral outcomes that is influenced on an individual level by motivations and cognitions; on an individual–other level by social harmony and public expression motivations; and on a social level by social context and media mechanisms. While research on perceptual outcomes remains highly supported, research on behavioral outcomes, as well as the mechanisms and moderating factors that produce those outcomes, require further research.

References:

- Cameron, N. (1947). The psychology of behavior disorders: A biosocial interpretation. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Davison, W. P. (1981). The third-person effect in communication. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47, 1–15.

- Dewey, J. (1922). Human nature and conduct. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- Eveland, W. P., Jr. (2002). The impact of news and entertainment media on perceptions of social reality. In J. P. Dillard & M. Pfau (ed.), The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 691–727.

- Fields, J. M., & Schumann, H. (1976). Public beliefs about beliefs of the public. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40, 427– 448.

- Gerbner, G., & Gross, L. (1976). Living with television: The violence profile. Journal of Communication, 27(2), 173 –199.

- Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Jackson-Beeck, M., Jeffres-Fox, S., & Signorielli, N. (1978). Cultural indicators: Violence profile no. 9. Journal of Communication, 30(3), 10 –29.

- Gibson, R., & Zillmann, D. (1994). Exaggerated versus representative exemplification in news reports: Perception of issues and personal consequences. Communication Research, 21(5), 603 – 624.

- Glynn, C. J., Ostman, R. E., & McDonald, D. G. (1995). Opinions, perception, and social reality. In T. L. Glasser & C. T. Salmon (eds.), Public opinion and the communication of consent. New York: Guilford, pp. 249 –277.

- Gunther, A. C. (1998). The persuasive press inference: Effects of mass media on perceived public opinion. Communication Research, 25(5), 486 –504.

- Gunther, A. C., & Chia, S. C. (2001). Predicting pluralistic ignorance: The hostile media perception and its consequences. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 78(4), 688 –701.

- Gunther, A. C., & Storey, J. D. (2003). The influence of presumed influence. Journal of Communication, 53(2), 199 –215.

- Hawkins, R. P., & Pingree, S. (1982). Television’s influence on social reality. In L. B. D. Pearl & J. Lazar (eds.), Television and behavior: Ten years of scientific progress and implications for the eighties. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, pp. 224 –247.

- Hayes, A. F., Glynn, C. J., & Shanahan, J. (2005). Willingness to self-censor: A construct and measurement tool for public opinion research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 17(3), 298 –323.

- Jones, P. E. (2004). Are we over or under-projecting and how much? Decisive issues of methodological validity and item type. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 55 – 68.

- Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communication. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Korte, C. (1972). Pluralistic ignorance about student radicalism. Sociometry, 35(4), 576 –587.

- Lewin, K., & Grabbe, P. (1945). Conduct, knowledge, and acceptance of new values. Journal of Social Issues, 16(3), 53 – 64.

- McLeod, J. M., & Chaffee, S. R. (1972). The construction of social reality. In J. T. Tedeschi (ed.), The social influence processes. Chicago, IL: Aldine-Atherton, pp. 50 – 99.

- Mead, G. H. (1930). Cooley’s contribution to American social thought. American Journal of Sociology, 35(5), 693 –706.

- Mullen, B., Atkins, J. L., Champion, D. S., et al. (1985). The false consensus effect: A meta-analysis of 115 hypothesis tests. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 262 –283.

- Mutz, D. C. (1998). Impersonal influence: How perceptions of mass collectives affect political attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Newcomb, T. M., Turner, R. H., & Converse, P. E. (1965). Social psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The spiral of silence: Public opinion, our social skin. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- O’Gorman, H. J., & Garry, S. L. (1976). Pluralistic ignorance: A replication and extension. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40, 449 – 458.

- Perloff, R. M. (1999). The third-person effect: A critical review and synthesis. Media Psychology, 1, 353 –378.

- Prentice, D. A., & Miller, D. T. (1993). Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(2), 243 –256.

- Price, V., & Allen, T. (1990). Opinion spirals, silent and otherwise: Applying small-group research to public opinion phenomena. Communication Research, 17, 369 –392.

- Robbins, J. M., & Krueger, J. I. (2005). Social projection to in-groups and out-groups: A review and meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(1), 32 – 47.

- Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The false consensus effect: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(2), 279 –301.

- Sherman, S. J., Presson, C. C., & Chassin, L. (1984). Mechanisms underlying the false consensus effect: The special role of threats to the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10, 127–138.

- Shrum, L. J., & Bischak, V. D. (2001). Mainstreaming, resonance, and impersonal impact: Testing moderators of the cultivation effect for estimates of crime risk. Human Communication Research, 27(2), 187–215.

- Shrum, L. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1993). Processes and effects in the construction of social reality. Communication Research, 20(3), 436 – 471.

- Suls, J., & Wan, C. K. (1987). In search of the false-uniqueness phenomenon: Fear and estimates of social consensus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 211–217.

- Taylor, D. G. (1982). Pluralistic ignorance and the spiral of silence: A formal analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 46, 311–335.

- Tyler, T. R., & Cook, F. L. (1984). The mass media and judgments of risk: Distinguishing impact on personal and societal level judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 693 –708.

- Vallone, R. P., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1985). The hostile media phenomenon: Biased perceptions and perceptions of media bias in coverage of the Beirut massacre. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(3), 577–585.