There is no single commonly accepted definition of framing in the field of communication. In fact, political communication scholars have offered a variety of conceptual and operational approaches to framing that all differ with respect to their underlying assumptions, the way they define frames and framing, their operational definitions, and very often also the criterion variables.

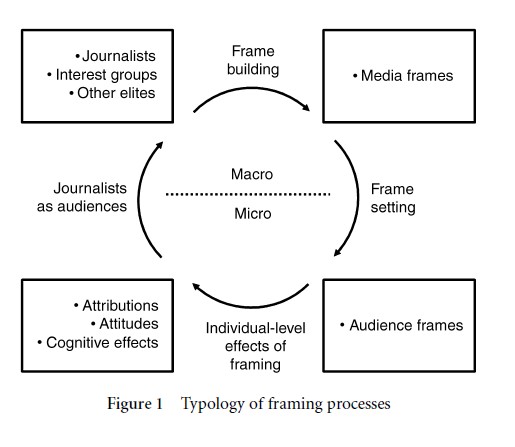

Previous framing research can be classified based on its level of analysis and the specific process of framing that various studies have focused on. In particular, Scheufele (1999) differentiated media frames and audience frames. Based on these two broader concepts, he distinguished four processes that classify areas of framing research and outline the links among them: frame building, frame setting, individual-level effects of framing, and journalists as audiences for frames.

Types Of Frames And Framing Processes

Media Frames VS Audience Frames

Media frames are defined as “a central organizing idea or story line that provides meaning to an unfolding strip of events” (Gamson & Modigliani 1987, 143). Media frames are important tools for journalists to reduce complexity and convey issues, such as welfare reform or stem cell research, in a way that allows audiences to make sense of them with limited amounts of prior information. For journalists, framing is therefore a means of presenting information in a format that fits the modalities and constraints of the medium they are writing or producing news content for and that also makes it possible for audiences to make sense of the information and integrate it into their existing cognitive schema.

Some view news frames as tools of spin and manipulation. Frames can certainly be used to manipulate the interpretation of messages by audiences. But it is important to note in this context that for most journalists framing is a tool that allows them to reduce complexity of issues and present them in a way that is easily accessible to wide cross-sections of the audience. Or as Tuchman says, “The news frame organizes everyday reality and . . . is part and parcel of everyday reality . . . , [it] is an essential feature of news” (1978, 193). Media frames serve as working routines for journalists that allow them to quickly identify and classify information and “to package it for efficient relay to their audiences” (Gitlin 1980, 7).

Individual Frames

Media frames work as organizing themes or ideas because they play to individual-level interpretive schema among audiences. These schemas are tools for information processing that allow people to categorize new information quickly and efficiently, based on how that information is framed or described by journalists. Framing research has often used the term “audience frame” to describe these schemas, defining them as “mentally stored clusters of ideas that guide individuals’ processing of information” (Entman 1993, 53).

Two types of frame of reference can be used to interpret and process information: global and long-term political views on the one hand, and short-term issue-related frames of reference on the other hand. Goffman’s (1974) idea of frames of reference refers to more long-term, socialized schemas that are often socialized and shared in societies or at least within certain groups in societies. But in addition to these more long-term and broadly shared schemas, there are also short-term issue-related frames of reference that are learned from mass media and that can have a significant impact on perceiving, organizing, and interpreting incoming information and on drawing inferences from that information (Pan & Kosicki 1993).

The Interplay Of Media And Audience Frames

The Price and Tewksbury (1997) applicability model of framing offers a theoretical explanation of how media frames and audience frames interact to influence individual perceptions and attitudes. They argue that frames work only if they are applicable to a specific interpretive schema. These interpretive schemas can be pre-existing ones that are acquired through socialization processes or other types of learning. But they can also be part of the message itself. For example, a news message may suggest a connection between tax policy and unemployment rates. The news message may suggest that the best way to think about whether higher or lower taxes are desirable is through a consideration of whether one wants higher or lower unemployment. Thus, the message has said that considerations about unemployment are applicable to questions about taxes.

Price and Tewksbury’s applicability model does imply that when audience members do not have an interpretive schema available to them in memory, and the schema is not provided in a news story, a frame that applies the construct in a message will not be effective. Framing effects therefore vary in strength as a partial function of the fit between the schemas a frame suggests should be applied to an issue and either the presence of those frames in audience members’ existing knowledge or the content of the message (Scheufele & Tewksbury 2007).

Theoretical Explanations Of Framing

This applicability model is consistent with the two larger theoretical or historical contexts within which researchers commonly examine framing: psychological approaches and sociological approaches.

Psychological Approaches

Psychological approaches to framing research are often traced back to Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s notions of bounded rationality, more broadly, and prospect theory, in particular (e.g., Kahneman & Tversky 1979). In 2002, Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions to this collaborative effort, and in his acceptance speech he nicely summed up the basic premise of prospect theory: “Perception is referencedependent” (Kahneman 2003a, 459). The idea of reference dependency assumes that a given piece of information will be interpreted differently, depending on which interpretive schema an individual applies. More importantly, however, different interpretive schemas can be invoked by framing the same message differently. Kahneman’s experimental work focuses mostly on the impact of framing on economic and risk-related choices, but the implications for communication research are obvious.

A good example is the coverage of the death of Rachel Corrie. Both Reuters and the Associated Press ran news releases, outlining the basic facts. Corrie, a member of the International Solidarity Movement, was run over and crushed to death by an Israeli army bulldozer on Sunday, March 16, 2003 while she was trying to stop it from tearing down a building in the Rafah refugee camp in the Southern Gaza Strip. The difference between the two news releases was that the AP release was accompanied by a file photo of Corrie burning a mock American flag, surrounded by Palestinian children, her face contorted with anger. The Reuters photograph instead showed her lying on the ground after being run over by the bulldozer, still covered in sand, surrounded by fellow protesters, with blood running down her face.

Similar to Kahneman’s example of ambiguous letters and numbers, this example highlights the idea of perceptions being reference-dependent. The written news story about Corrie’s death can be interpreted quite differently, depending on which visual image is used to frame the account of events. The image, in other words, sets the context for or “frames” any subsequent information processing.

Sociological Approaches

Sociological approaches to framing are often traced back to Erving Goffman’s (1974) notion of frames or primary frameworks. Goffman assumes that individuals cannot understand the world fully and therefore actively classify and interpret their life experiences to make sense of the world around them. An individual’s reaction to new information therefore depends on interpretive schemas Goffman calls “primary frameworks” (Goffman 1974, 21). In particular, Goffman distinguishes between natural and societal frames similar to Heider’s (1978) notion of attributions to personal or environmental factors: natural frames help to interpret events originating from natural and non-intentional causes, whereas societal frames help “to locate, perceive, identify, and label” actions and events that stem from intentional human action (Goffman 1974, 21). Based on Goffman’s ideas, there are various ways in which journalists can portray any given event in news coverage. And which portrayal is chosen depends on the framework employed by the journalists.

Framing As A Multilevel Construct

The term “framing” has been used almost interchangeably to describe individual-level media effects, macro-level influences on news content, and other related processes. At least four interrelated processes involving framing at different levels of analysis have been identified (Fig. 1).

The first of these processes is frame building. Frame building refers to the linkages between various intrinsic and extrinsic influences on news coverage and the frames used in news coverage. These influences include the personal predispositions of journalists, organizational routines and pressures, the efforts by outside groups to promote certain frames, the impact of other parallel issues or events, and the type of policy arena where decision-making or conflict might take place (Shoemaker & Reese 1996).

Frame setting, the second process, refers to the process of frame transfer from media outlets to audiences. Some communication researchers have suggested that this frame-setting effect is conceptually similar to the transfer of salience hypothesized in the agenda-setting model. Recent research, however, has shown that the two processes rely on distinctly different theoretical premises and cognitive processes (for an overview, see Scheufele 2000; Scheufele & Tewksbury 2007).

Figure 1 Typology of framing processes

Most communication research has focused on a third process: individual-level effects of framing. These individual-level outcomes include attributions of responsibility, support for various policy proposals, or citizen competence (Druckman 2001; Iyengar 1991). Unfortunately, while making important contributions in describing effects of media framing on behavioral, attitudinal, or cognitive outcomes, most of these studies have not provided systematic explanations as to why and how these variables are linked to one another. Price and Tewksbury’s (1997) notion of applicability effects outlined earlier provides a first step in this direction.

The last process related to framing that political communication scholars have explored is the idea of journalists themselves as audiences for frames. Without directly referring to the idea of framing, Fishman (1978; 1980) suggests that, similar to “regular” audiences, journalists are indeed susceptible to frames set by news media. Fishman’s study demonstrates how news coverage of isolated crimes in a community was framed as a “crime wave against the elderly” by initially a small number of local media and how that frame was soon picked up by other journalists and spread across other news outlets and communities. Fishman labels this phenomenon a “news wave.”

Unresolved Issues In Framing Research

Framing research continues to struggle with at least three unresolved issues related to how the concept has been defined or measured.

Framing As A Type Of Agenda Setting?

Some scholars (e.g., McCombs 2004) have argued that framing is just a conceptual extension of agenda setting. Similar to agenda setting, they argue, framing increases the salience of certain aspects of an issue and therefore can be labeled “second-level agenda setting.”

A number of scholars, however, have rejected that notion (for an overview, see Price & Tewksbury 1997; Scheufele 2000; Scheufele & Tewksbury 2007). Rather, agenda setting is based on the notion of attitude accessibility. Mass media have the power to increase levels of importance assigned to issues by audience members or the ease with which these considerations can be retrieved from memory if individuals have to make political judgments about political actors. Framing is based on the concept of context-based perception, that is, on the assumption that subtle changes in the wording of the description of a situation might affect how audience members interpret this situation. In other words, framing influences how audiences think about issues, not by making aspects of the issue more salient, but by invoking interpretive schema that influence the interpretation of incoming information.

Is There A Consistent Set Of Frames?

The second unresolved area of framing research concerns the different types of frames identified in previous research. Scholars have operationalized media frames along dichotomies, such as episodic vs thematic frames (Iyengar 1991) or issue vs conflict frames (Cappella & Jamieson 1997) or game schema coverage (Patterson 1993). Other studies examined frames along content areas, such as conflict frames, human interest frames, or consequence frames (Price et al. 1997). What has been missing, however, is an examination of a set of frames that could potentially be applicable across issues. By taking an inductive approach, previous research has identified unique sets of frames with each new study. As a result, communication researchers continue to have only a limited understanding of the specific frames that can trigger certain underlying interpretive schemas among audiences and therefore lead to various behavioral or cognitive outcomes.

Framing In The Lab VS Real World?

The final challenge for communication researchers is the inherent conflict between the different approaches to framing research that originated from the psychological and sociological foundations of the concept outlined earlier. In particular, Kahneman’s (2003b) early experimental research focused on a very narrow but highly internally valid approach to studying framing. For Kahneman, framing a message means to keep the content absolutely constant and to manipulate only the mode of presentation or the context within which the information is presented. Based on more sociological approaches, however (e.g., Tuchman 1978), it is questionable to what extent it is possible to create real-world examples of news articles that are framed in different ways, but do not differ in terms of content. In short, framing in everyday journalism probably means a mixture of changes, both in terms of content and mode of presentation. And externally valid studies of framing effects will have to balance the desire for internally valid designs with the need for externally valid stimulus materials. Message effects in the real world are confounds of persuasive content effects and modality-or presentation-based framing effects.

References:

- Cappella, J. N., & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Druckman, J. N. (2001). Credible advice to overcome framing effects. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 17, 62 – 82.

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51–58.

- Fishman, M. (1978). Crime waves as ideology. Social Problems, 25, 531–543.

- Fishman, M. (1980). Manufacturing the news. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1987). The changing culture of affirmative action. In R. G. Braungart & M. M. Braungart (eds.), Research in political sociology, vol. 3. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, pp. 137–177.

- Gitlin, T. (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making and unmaking of the new left. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper and Row.

- Heider, F. (1978). Über Balance und Attribution [On balance and attribution]. In D. Görlitz, W.-U. Meyer, & B. Weiner (eds.), Bielefelder Symposium über Attribution. Stuttgart, Germany: Klett, pp. 19 –28.

- Iyengar, S. (1991). Is anyone responsible? How television frames political issues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kahneman, D. (2003a). Maps of bounded rationality: A perspective on intuitive judgment and choice. In T. Frängsmyr (ed.), Les Prix Nobel: The Nobel Prizes 2002. Stockholm, Sweden: Nobel Foundation, pp. 449 – 489.

- Kahneman, D. (2003b). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist, 58(9), 697–720.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: Analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263 –291.

- McCombs, M. E. (2004). Setting the agenda: The mass media and public opinion. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Pan, Z., & Kosicki, G. M. (1993). Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication, 10, 55 –75.

- Patterson, T. E. (1993). Out of order, 1st edn. New York: Knopf.

- Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1997). News values and public opinion: A theoretical account of media priming and framing. In G. A. Barett & F. J. Boster (eds.), Progress in communication sciences: Advances in persuasion, vol. 13. Greenwich, CT: Ablex, pp. 173 –212.

- Price, V., Tewksbury, D., & Powers, E. (1997). Switching trains of thought: The impact of news frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Communication Research, 24, 481–506.

- Scheufele, D. A. (1999). Framing as a theory of media effects. Journal of Communication, 49(1), 103 –122.

- Scheufele, D. A. (2000). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: Another look at cognitive effects of political communication. Mass Communication and Society, 3(2/3), 297–316.

- Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda-setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9 –20.

- Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (1996). Mediating the message: Theories of influences on mass media content, 2nd edn. White Plains, NY: Longman.

- Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. New York: Free Press.