The priming effect refers to media-induced changes in voters’ reliance on particular issues as criteria for evaluating government officials. The more prominent any given issue in the news, the greater the impact of voters’ opinions about that issue on their evaluations of government. The priming effect creates volatility in public opinion, especially during election campaigns. As casual observers of the political scene, ordinary citizens only notice events and issues that are in the news; those not covered by the media might as well not exist. What is noticed becomes the principal basis for the public’s beliefs about the state of the country. Thus, the relative prominence of issues in the news is the major determinant of the public’s perceptions of the problems facing the nation (see, e.g., Iyengar and Kinder 1987).

The relationship between news coverage and public concern has come to be known as the agenda-setting effect. Over the past four decades, agenda-setting effects have been replicated in numerous studies. Cross-sectional surveys, panel surveys, aggregate-level time-series analyses of public opinion, and laboratory experiments all converge on the finding that issues in the news are the issues that people care about.

Priming As An Extension Of Agenda Setting

Beyond merely affecting the salience of issues, news coverage influences the criteria the public uses to evaluate political candidates and institutions. A simple extension of agenda setting, priming describes a process by which individuals assign weights to their opinions on particular issues when they make summary political evaluations. In general, the evidence indicates that when asked to appraise politicians and public figures, voters weight opinions on particular policy issues in proportion to the perceived salience of these issues: the more salient the issue, the greater the impact of opinions about that issue on the appraisal (for reviews of priming research, see Miller & Krosnick 2000; Druckman 2004).

Their dynamic nature make priming effects especially important during election campaigns. Consider the case of the 1980 American presidential campaign. Less than a week before the election, polls showed Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan to be dead even. Suddenly, the Iranian government offered a last-minute proposal for releasing the Americans held hostage for over a year. President Carter suspended his campaign to devote his full attention to these negotiations. The hostage story became the major news item of the day. The prominence of the hostage story caused voters to seize upon the candidates’ ability to control terrorism as a basis for their vote choice (Iyengar & Kinder 1987). Given his unimpressive record on this issue while in office, the effect proved disastrous for President Carter.

Similar volatility in the state of the public agenda bedeviled President George H. Bush in the 1992 election. One year previously, he had presided over the successful liberation of Kuwait from Iraqi occupation and his popularity ratings reached 90 percent. But as news coverage of the economy gradually drowned out news about the Gulf conflict, voters came to prefer Clinton over Bush. Had the media played up military or security issues, of course, the tables would have been turned.

Figure 1 Ingredients of President Bush’s popularity Source: Gallup CBS News Polls and Gallup polls, 2001–2004

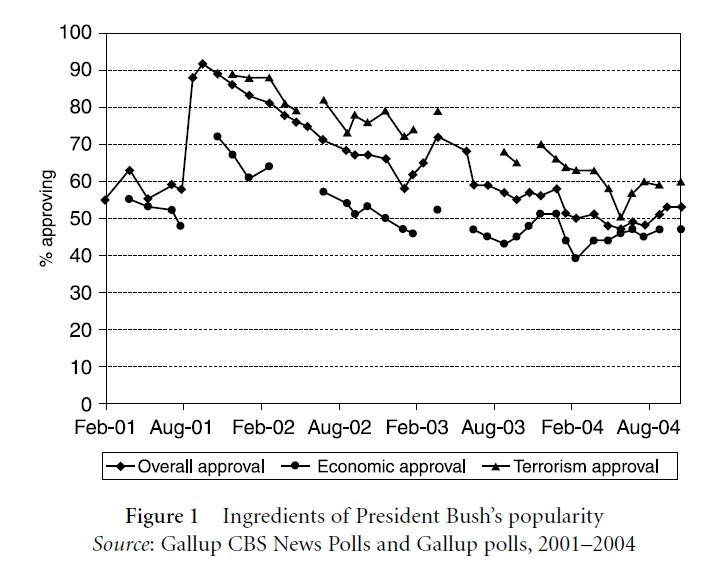

The most recent instance of priming comes from the post-9/11 era. Prior to September 11, President George W. Bush’s overall popularity was closely tied to perceptions of his performance on economic issues (see Fig. 1). After September 11 and extending through 2003, however, Bush’s popularity was more closely tied to assessments of his performance on terrorism. Terrorism and national security had replaced the economy as the yardstick for judging Bush’s performance. It was only in 2004, after the onset of the presidential campaign, that economic performance and overall performance were again linked. This finding is reinforced by a time-series analysis of Bush’s popularity (see Iyengar & McGrady 2007), which demonstrates that following the 9/11 attacks, news coverage of terrorism became the single most important determinant of Bush’s public approval.

Ancillary Conditions For Priming Effects

Media priming effects have been documented in a series of experiments and surveys, with respect to evaluations of presidents, legislators, and lesser officials, and with respect to a variety of attitudes ranging from voting preferences, assessments of incumbents’ performance in office, and ratings of candidates’ personal attributes to racial and gender identities. In recent years, the study of priming has been extended to arenas other than the United States, including a series of elections in Israel (Sheafer & Weimann 2005), Germany (Schoen 2004), and Denmark (de Vreese 2004).

Typically, news coverage of issues elicits stronger priming effects in the area of performance assessments than in the area of personality assessments (Iyengar & Kinder 1987). In one noteworthy exception – involving “personality priming” – voters who watched the famous 1960 debate between John Kennedy and Richard Nixon on television were more likely to rely on image factors (such as integrity) when considering the candidates’ performance in the debate (see Druckman 2003) than were voters who listened to the debate on the radio. The radio group, on the other hand, took into account both image and the candidates’ positions on the issues. This study suggests that the visual imagery provided by television encourages voters to focus on personality related rather than issue-related considerations when evaluating the candidates.

A special case of priming concerns the phenomenon of momentum in primary elections. Because news coverage during the early primaries tends to focus exclusively on the state of the “horse race,” primary voters are likely to rely heavily on information about the candidates’ electoral viability when making their choices (Brady & Johnston 1987). In a study of the 2004 primary campaign, researchers found that the single most important determinant of Democrats’ primary vote preference between senators John Kerry and John Edwards was the voters’ perceptions of the two candidates’ personalities. The secondmost powerful predictor of vote choice was the candidates’ electoral viability (Iyengar et al. 2004). Viability was more important to voters than the candidates’ positions on major issues, including the war in Iraq and outsourcing of American jobs.

The ability of the news media to prime political evaluations depends on both media content and the predispositions of the audience. Unsurprisingly, priming effects peak when news reports explicitly suggest that politicians are responsible for the state of national affairs, or when they clearly link politicians’ actions with national problems. Thus, evaluations of President Reagan’s performance were more strongly influenced by news stories when the coverage suggested that “Reaganomics” was responsible for rising American unemployment than when the coverage was directed at alternative causes of unemployment (Iyengar & Kinder 1987, ch. 9).

In a further parallel with agenda-setting research, individuals differ in their susceptibility to media priming effects. Miller and Krosnick (2000) found that priming effects occurred only among people who were highly knowledgeable about political affairs and had high levels of trust in the media. Iyengar and Kinder (1987) found that partisanship affected the issues on which people could be primed: Democrats tended to be most susceptible to priming when the news focused on issues that favor Democrats, such as unemployment and civil rights, while Republicans were influenced most when the news focused on traditional Republican issues like national defense.

In sum, issues and events in the news are deemed important and weigh heavily in evaluations of incumbent officials and political candidates. As is clear from the way in which President George H. Bush benefited from media coverage of the 1991 Gulf War and then suffered from coverage of the economy, priming results equally from news of political successes and news of political failures. Priming is a double-edged sword.

References:

- Brady, H. E., & Johnston, R. (1987). What’s the primary message: Horse race or issue journalism? In G. R. Orren & N. W. Polsby (eds.), Media and momentum: The New Hampshire primary and nomination politics. Chatham, NJ: Chatham House, pp. 127–186.

- de Vreese, C. H. (2004). Primed by the euro: The impact of a referendum campaign on public opinion and evaluations of government and political leaders. Scandinavian Political Studies, 27(1), 45–64.

- Druckman, J. N. (2003). The power of television images: The first Kennedy–Nixon debate revisited. Journal of Politics, 65, 559–571.

- Druckman, J. N. (2004). Priming the vote: Campaign effects in a U.S. Senate election. Political Psychology, 25, 577–594.

- Druckman, J. N., & Holmes, J. W. (2004). Does presidential rhetoric matter? Priming and presidential approval. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 34, 755–778.

- Iyengar, S., & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that matters: Television and American opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Iyengar, S., & McGrady, J. (2007). Media politics: A citizen’s guide. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Iyengar, S., Luskin, R., & Fishkin, J. (2004). Deliberative public opinion: Evidence from presidential primaries. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association.

- Miller, J. M., & Krosnick, J. A. (2000). News media impact on the ingredients of presidential evaluations: Politically knowledgeable citizens are guided by a trusted source. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 295–309.

- Schoen, H. (2004). Candidate orientations in election campaigns. An analysis of the German federal election campaigns 1980–1998. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 45(3), 321–345.

- Sheafer, T., & Weimann, G. (2005). Agenda building, agenda setting, priming, individual voting intentions, and the aggregate results: An analysis of four Israeli elections. Journal of Communication, 55(2), 347–365.