Since the modern era in the west, art has increasingly been defined as distinct from communication. Since Kant and Hume, discriminations of sensory beauty and “delicacy of taste” have been invoked in judgments of aesthetic value that separate those forms of communication that qualify as art from those that do not. Gross has argued that an important part of the process of art appreciation is the “perception and evaluation of the competence displayed by the artist” (Gross 1973, 124). That is, does the reader or viewer attribute skill on the part of the artist to “the selecting, transforming, and ordering of the elements” (Gross 1973, 127) that constitute the work of art, and see these creative actions as intentional? For Gross these demonstrations of competence may be appreciated anonymously, as examples of conventionally recognized ability or talent, but most often they depend upon the valorization of an individual artist, the repository of the skill that is distinguished.

Yet in most cultures for most of human history, the creation of art has been a socially organized activity, central to the communication of shared religious beliefs, mythic understandings of the world, and social relations. Indeed, the rise of technologies of mass communication were theorized in the twentieth century in terms of their relationship to the traditional arts, and the resulting media content often characterized as “popular arts,” the product of newly emerging “culture industries” (Seldes 1956; Lowenthal 1984; Adorno 2001).

Modernist definitions of art as nonutilitarian and honorific have tended to separate art activity from religion, education, craft, and other forms of functional communication in favor of an emphasis on individual self-expression, formalism, emotional evocation, or representations of the mysterious, the subconscious, or the ineffable. This has involved a movement away from the reaffirmation of common cultural knowledge and shared community values toward the marking of elite knowledge and memberships. Thus, the main recent sense of the word “art” has referred to “creative” or “fine” art, and its communicative effect has shifted from the conscious articulation of social knowledge and cultural heritage to the idea of unique and innovative individual expression. Modern fine art has even been described as a “project of negation,” that is, the progressive breaking free from established cultural practices, generating “a growing canon of prohibitions: representation, figuration, narration, harmony, unity” (Bernstein 2001, 21).

Art, Culture, And Social Relations

Defined as a human activity transcending modern history and modernist aesthetic philosophy, art is more likely to be seen as a wide-ranging process of creative production that reflects and projects social relations, political power, and cultural beliefs and practices. As such, it encompasses ancient architectural structures, statues, obelisks, basreliefs, pottery, masks, and funerary arts, as well as the conventional fine arts of poetry, literature, drama, music, painting, and prints. These and other forms of artistic creativity have functioned as powerful social communication in virtually all cultures, reproducing established cultural heritage (Bourdieu & Passeron 1977) and the ideological assumptions and social order of those social, economic, and political structures that support, or require, their creation.

Studies in the sociology and social history of art identify artistic production as both the communication of prevalent ideas in a particular culture at a specific point in history, and, on a more micro-level, the result of the specific institutional and organizational contexts in which production processes, individual and collective, take place. Thus Baxandall (1972) documents the system of contractual agreements between patron and painters in fifteenth-century Italy, explaining how required applications of gold leaf and aquamarine to a painting’s surface served to publicize or reaffirm the patron’s social status. Wolff (1993) asserts that the modernist notion of the alienated artist working against the grain of social convention is itself a historically specific concept resulting from the breakdown of patronage, and from the separation of production from consumption in capitalist markets. The artist’s dependence on impersonal markets, she notes, is not so different from the limited autonomy of all workers, and art in late modernism can be seen to communicate essential features of late capitalism.

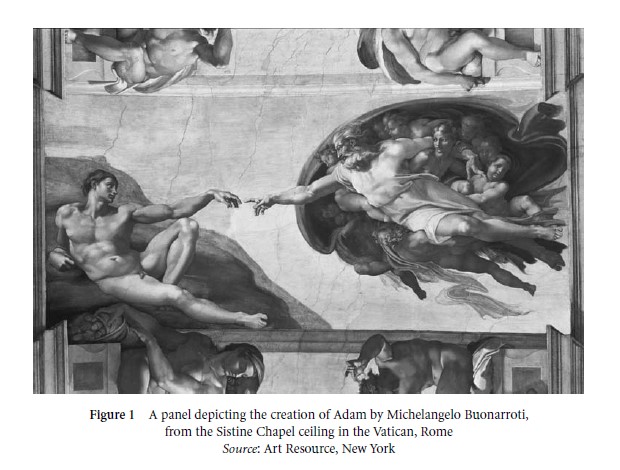

Berger (1972), building from Benjamin (1968), makes a similar argument about the transformation of art from unique creations made to fulfill a particular role in a specific place and time, to art in the modern era that is easily reproduced and proliferates in multiple forms and contexts. The communicational function of paintings, such as those done by Michelangelo to adorn Pope Julius II’s Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, shifts when panels of the ceiling are lifted from their original context and reproduced in advertisements or on T-shirts. The original design and placement of such paintings had significant religious and doctrinal implications. A central panel of the Sistine Chapel ceiling contains a painting that visually links the creation of Adam to the future coming of woman and the Christ child, Jesus (Fig. 1). As part of a sequence of illustrations depicting scenes from the Book of Genesis that projects above the pope’s own chapel, this image creates a powerful visible connection between ideas and beliefs concerning the creation of man, the salvation of mankind, the church, and the pope himself. To remove any part of this tangibly coordinated arrangement and reproduce it elsewhere is to lose the original constellation of potential meaning, and to create a new network of references within a different social and physical context.

Figure 1 A panel depicting the creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti, from the Sistine Chapel ceiling in the Vatican, Rome

Art’s function as communication is highly dependent upon its specific social use within particular institutional and organizational networks. In the modern era, as forms of art were loosed from traditionally situated contexts and reproduced within the more ephemeral flows of industrial communication media, a tension developed between humanist conceptions of art as transcendent creativity and sociological and materialist conceptions of art as a form of social communication. Marxist literary critics and art historians emphasized art as a product of the “social and ideological contingencies” of specific historical circumstances. “Humanist criticisms of the sociology of literature and art,” according to Wolff, “are often . . . attempts to rescue a notion of ‘creativity’ which allows to art a special transcendence of all contingencies, particularly social and ideological contingencies” (1993, 69).

For European and American sociologists in the twentieth century, the fragmentation of art forms and the rise of mass-mediated popular culture effaced distinctions between art and craft at the same time as it reinforced the notion of “fine art” as a symbolic indicator of social status. Mass culture critics of the post-World War II era observed the degradation of both authentic “folk art” and “high art” by the proliferation of a standardized and parasitic “mass culture” (Rosenberg & White 1957; Bernstein 2001). Gans (1974) argued for a more nuanced view, describing a more elaborately class-stratified, yet democratic, hierarchy of taste cultures. Bourdieu described knowledge of and participation in art as an important constituent of “cultural capital” enhancing the communication of social power and status (Bourdieu & Passeron 1977). Becker (1982) has foregrounded the collective nature of artistic production, consumption, and valuation, pointing to the meaning of artistic activity for the social communication of groups. The cooperative creation of artworks (in art studios, camera clubs, or film crews), the viewing, reception, and purchase of artistic products by audiences and networks of fans or connoisseurs, and the definition and evaluation of art itself by educational institutions, galleries, and museums, all involve the sharing and exercise of assumptions, communication practices, and definitions within social groups (Phillips 1982; Bourdieu 1991; Gross 1995).

Sociologies of art have effectively expanded the definition of art beyond “fine art” to include media or popular arts. Photography and the cinema, having been institutionalized in the museum and education systems, are now widely accepted as art forms. Popular music, dance, and theatre (along with film and television) have come to be known as the “performing arts.” Advertising art has become perhaps the most ubiquitous form of imagery in the world, reflecting a movement away from aristocratic, religious, and state culture and power to business or corporate culture and power. Yet visual and verbal references to fine art are still commonplace in advertising, employed as signs meant to communicate social prestige.

Visual Art As Design And Illustration

The capacity of figural and pictorial art to provide literal mappings and reflections of the world has facilitated the descriptive power of visual media, and by extension its persuasive and manipulative potential. Edgerton (1991) makes the case that developments of pictorial perspective in the visual art of late medieval and Renaissance Europe directly contributed to the communication and diffusion of scientific knowledge and the acceleration of the technological advances that followed. The potential for mimetic art to convincingly represent realistic scenes, situations, and relationships enhances its power to communicate persuasively about the social world, blurring the boundaries between art, entertainment, advertising, and information. But as Edgerton demonstrates, the design practices of picture-makers, in this case the precision of the geometric schema developed for perspectival grids, not just the appearance of naturalism, can powerfully influence the role of art in communication.

Today, what have come to be known as the digital arts involve techniques of design, and the use of iconographic symbol systems, as much as or more than naturalistic depictions. Iconography, the study of the range of pictorial symbols that a culture uses systematically to convey meaning, is as relevant to contemporary television, or the world wide web, as it is to Japanese landscape painting or the religious painting of medieval Europe. What has become more uncertain in contemporary media arts is the degree to which artistic evaluation relates to effective communication, or to the recognition of skillful execution. Often in the past, the value of art was inseparable from its value as communication. Today, art and visual communication have become ever more separately defined.

It might be argued that things have not changed so much, that art is still most important for its role as a marker of social position, its function as social communication. But the functions of artistic communication have multiplied, and its emphases have shifted: from providing material as painting, print, or building for the propagation of dominant or shared cultural ideas, values, and beliefs (Worth 1981; Bourdieu 1993), to the recognition and appreciation of skill in the performance of shared cultural practices (Gross 1973), to the romanticization and celebration of the artist as alienated, heroic, or tragic figure, and finally to the modernist distinctions between art and communication that continue to serve as powerful signs of social membership, status, and taste (Bourdieu 1984). These shifts may primarily represent changes in the perceived roles of audience members, from ready acceptance of cultural heritage and social destiny, to active appreciation of culturally valued skills, to resistance against convention and a desire for greater freedom, to alienated and divided consumers of taste cultures.

References:

- Adorno, T. (2001). Culture industry reconsidered. In J. Bernstein (ed.), The culture industry: Selected essays on mass culture. London: Routledge, pp. 98 –106. (Original work published 1975).

- Baxandall, M. (1972). Painting and experience in fifteenth-century Italy: A primer in the history of pictorial style. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Becker, H. S. (1982). Art worlds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Benjamin, W. (1968). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In W. Benjamin, Illuminations (ed. and intro. H. Arendt, trans. H. Zohn). New York: Schocken Books. (Original work published 1936).

- Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. London: Penguin.

- Bernstein, J. (ed.) (2001). The culture industry: Selected essays on mass culture. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste (trans. R. Nice). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). The love of art: European museums and their public (trans. C. Beattie & N. Merriman). Cambridge: Polity.

- Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London: Sage.

- Edgerton, S. Y. (1991). The heritage of Giotto’s geometry: Art and science on the eve of the scientific revolution. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Gans, H. (1974). Popular culture and high culture: An analysis and evaluation of taste. New York: Basic Books.

- Gross, L. (1973). Art as the communication of competence. Social Science Information, 12, 115 –141.

- Gross, L. (ed.) (1995). On the margins of art worlds. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Lowenthal, L. (1984). Literature and mass culture: Communication and society, vol. 1. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Phillips, C. (1982). The judgment seat of photography. October, 22, 27– 63.

- Rosenberg, B., & White, D. M. (eds.) (1957). Mass culture. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Seldes, G. (1956). The public arts. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Wolff, J. (1993). The social production of art, 2nd edn. New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Worth, S. (1981). Studying visual communication (ed. and intro. L. Gross). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.