There is no more difficult concept to clearly define than that of propaganda. Countless books and learned essays have grappled with a definition of this persuasive practice that would encompass all of its many manifestations. The difficulty in arriving at a definition that satisfies all aspects of this particular type of persuasive behavior is compounded by the historical shift in the acceptance of those activities that today might be labeled as propaganda. Propaganda, in its most neutral sense, means to disseminate or promote particular ideas. A working definition of propaganda which focuses on the communication process is as follows: “Propaganda is the deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist” (Jowett & O’Donnell 2006).

The concept of persuasion is an integral part of human nature and the use of specific techniques to bring about large-scale shifts in ideas and beliefs can be traced back to the ancient world. While propaganda activities utilize a wide range of media and virtually every form of human social interaction, the utilization of visual media has been particularly effective throughout human history. The psychological effect attained through the visual sense is particularly powerful, and tends to lend a sense of credibility and veracity, as well as providing a strong emotional response. From the earliest periods of recorded history we have numerous examples of visual stimuli used as propaganda devices to convey a sense of power, control the flow of information, or manipulate the emotions and cognitions of the public.

The Early History Of Visual Propaganda

Ancient Days

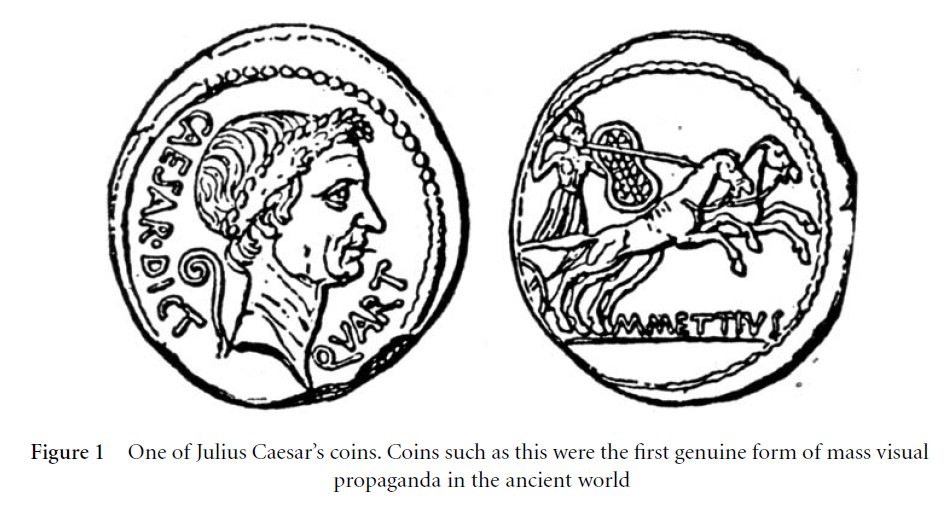

The development of visual propaganda throughout history moves along two basic trajectories. The first is the desire to disseminate the message to an ever-wider public; the second is to disseminate this message as quickly and effectively as possible. In the ancient world, where communications were severely limited by distance, visual propaganda was initially confined to monumental displays associated with official sites of power such as palaces and temples, where large architectural structures, statues, obelisks, wall engravings, and other visual devices were used as a means of establishing a sense of power, social order, and hierarchy. As transportation and communications improved in the ancient world, new methods of visual propaganda emerged as a means of creating and maintaining a sense of unity and stability across far-flung regions. In particular, the use of coins, circulated widely and embossed with the visual images of rulers and symbols of state, were extremely effective as a means of conveying the importance and centrality of the state in the lives of people (Fig. 1).

Julius Caesar (100–44 bce) was particularly adept at using sophisticated propaganda techniques. He used coins to advertise his victories or display himself in various guises, such as warlord, god, or protector of the empire. Caesar also made maximum use of the public spectacle, spending lavishly on massive triumphal processions to celebrate military victories.

The Emergence Of Print

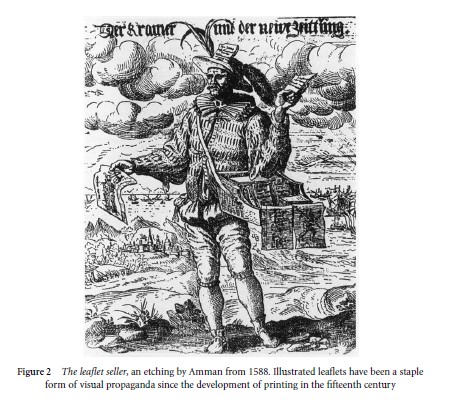

Until the fifteenth century, aside from coins, there was no means of duplicating imagery on any large scale in the west. Pictures were made for palaces, churches, and monasteries and did not travel. With the development of printing, it was possible to produce visual imagery as well as textual material in large quantities and transportable forms. In many ways, printing can be seen as the first mass production industry, and the modern age begins with the negation of the uniqueness found in the previous forms of handwritten communication.

Figure 1 One of Julius Caesar’s coins. Coins such as this were the first genuine form of mass visual propaganda in the ancient world

Figure 2 The leaflet seller, an etching by Amman from 1588. Illustrated leaflets have been a staple form of visual propaganda since the development of printing in the fifteenth century

The eventual development of woodblock prints, and later engravings on metal, was a significant breakthrough in the development of visual propaganda. Now the visceral power of the image, often accompanied by written text, could be widely disseminated in the form of broadsheets or pamphlets. These visual prints were intended to elucidate current events for the common man, and were focused to a large extent on religious or political themes. This new form of visual communication fostered a new profession, that of the engraver-artist. Lucas Cranach (1472–1553) was a master engraver whose work was of enormous assistance to Martin Luther’s propaganda campaign against the Roman Catholic Church. His portraits celebrated the reformers and supporting Protestant princes as heroes, and his caricatures satirized the pope and the Roman Church. These early propaganda prints were sold on the streets, and widely circulated, and were the forerunner of the extensive use of printed material in the development of propaganda techniques in the modern age (Fig. 2).

The emergence of printed propaganda signaled a major shift away from the feudal power structure of the Middle Ages into a modern “bourgeois” mentality. It was at this point that propaganda as a deliberate, systematic strategy to alter perceptions, beliefs, and actions of politically engaged publics begins to emerge, fueled by new forms of communication capable of reaching a wide audience within a relatively short period of time. Propaganda, especially in the form of visual stimuli, enters the structure of the modern political state as a powerful weapon both of groups opposed to authority and those in power, and prints and other forms of visual propaganda such as flags, heraldry, medals, regalia, and all manner of art and architecture were used to legitimize authority and symbolize the inherent power of the state.

New forms of printing accelerated this development. Lithographic printing was invented in 1798 by Alois Senefelder, and by 1848, could produce 10,000 sheets per hour. In 1856, the element of color was added, leading to the emergence of the “golden age of posters” in the late nineteenth century. While posters had been around for centuries, the new printing techniques now available precipitated and encouraged the emergence of the poster as the foremost medium of visual propaganda in the pre-motion picture and television ages. In both of the great wars of the twentieth century the poster became a major propaganda weapon, especially in creating morale and civic motivation on the home front with slogans like “Loose lips sink ships” and “Is your journey really necessary?”

Modern Days

Photography And Motion Pictures

The emergence of photography in the 1830s created an entirely new possibility for increasing the effectiveness and emotional impact of visual propaganda. By the 1860s the use of photography as a dramatic illustration of the horrors of war or the plight of the poor in slum living conditions had become a major weapon for the propagandist, despite the fact that such photographs were often deliberately staged by the propagandist as a means of influencing public opinion. By the turn of the century photographs could be mechanically reproduced in newspapers and magazines, and between the world wars, picture magazines such as the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung and the Münchner Illustrierte Presse in Germany, Vu in France, the Picture Post in the UK, and Life and Look in the US provided the major visual news experience for a mass public.

Photography proved to be a particularly powerful propaganda tool in the hands of skilled photographers such as Robert Capra, with his famous “Moment of death” picture from the Spanish Civil War, or Dorothea Lange, and her work in Appalachia for the New Deal administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Heinrich Hoffman’s carefully crafted pictures of Adolf Hitler contributed greatly to the Nazi iconography, and were found in almost every home in Germany during that period.

The use of photographs continues to be a major weapon in the propaganda arsenal, but the digitization of photography and the potential for the manipulation of the image has both created the potential for greater “agitative creativity” and caused a growing distrust of the pictorial image as an indication of “reality.”

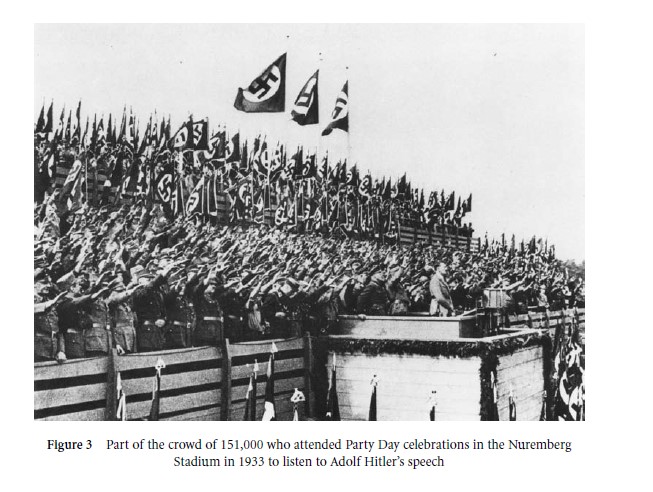

Figure 3 Part of the crowd of 151,000 who attended Party Day celebrations in the Nuremberg Stadium in 1933 to listen to Adolf Hitler’s speech

The motion picture has always been an enigma when it comes to its use as a propaganda weapon. Even as early as the 1890s, films taken of the Boer War (many of these were faked) were shown in British and American cinemas for propaganda purposes. By the time of World War I, the cinema was so popular with the international public that motion pictures became an integral part of the “official” propaganda activities of most governments. However, through its long history as an important and successful entertainment medium, the motion picture has had a checkered history of success as a vehicle for disseminating propaganda. There are, of course, individual films such as director Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the will (1935), a brilliant cinematic paean to Hitler’s 1934 Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg (see Fig. 3), or current controversial documentaries, such as Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 (2005), which can be seen as successfully communicating their propaganda objectives, but there are far more films that have failed to achieve the desired result of their propagandist creators. It appears that over time movie audiences have come to expect entertainment, and resent being confronted with explicitly political content. The most successful forms of motion picture propaganda have always come in the guise of entertainment. The depiction of “the American way of life” in countless Hollywood films, for example, seems to have had a greater impact on foreign audiences than a myriad of propaganda documentaries turned out by the US government.

Television

Television was first introduced to the world in the 1930s, when it was broadcast to small, elite audiences in Britain and Germany. The Nazis immediately attempted to exploit both their scientific breakthrough and their athletic prowess by televising the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, but this demonstration was available only to a small number of the Nazi Party elite and to the general public in tiny viewing rooms. Nevertheless, this exhibition established television’s potential as a propaganda medium. The British used their early experiments with television to broadcast entertainment, thus setting a precedent for an entirely different model of how television would be used. In the United States, television was introduced in the late 1940s, largely as a visual extension of highly popular commercial radio networks, and there was never any real question of its “power to persuade” being usurped by governmental or other potential agencies of propaganda. Of course, if we include advertising as a form of propaganda, then television has indeed succeeded in becoming the largest propaganda medium in the world. Even the use of television for formal educational purposes, a role for which it was ideally suited, never achieved the potential that had been part of its promise for so long.

Because of the technological barriers to broadcasting television signals across oceans and borders, it has only been in the past 25 years that the development of satellite television has created the potential for global television propaganda. However, here too the public has shown a marked preference for entertainment programming, but in very recent years, particularly with growing international conflicts in the former Soviet Union, the Balkans, and the Middle East, satellite television news channels such as Fox News, CNN, and Al Jazeera have begun to emerge as significant sources for delivering propaganda messages. The continuous broadcasting of images of conflict, many “live” as they are unfolding, has made these satellite channels, as well as the traditional broadcast networks, among the most powerful propaganda agencies now in existence.

New communication technologies, including hand-held mobile phone devices, digital cameras, and palm-sized computer interfaces, all linked to the Internet, promise to facilitate the dissemination of imagery which could be used for a wide variety of propaganda purposes. Government attempts to regulate such widespread use of visual devices have proven to be rather futile, and there is little doubt that in the future the free flow of imagery will only increase, providing an even greater potential for diverse expression, but also for manipulation and the creation of more powerful visual propaganda.

References:

- Clark, T. (1997). Art and propaganda in the twentieth century: The political image in the age of mass culture. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Jowett, G. S., & O’Donnell, V. (2006). Propaganda and persuasion, 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lehmann-Haupt, H. (1954). Art under a dictatorship. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lindey, C. (1990). Art in the Cold War: From Vladivostok to Kalamazoo, 1945–1962. London: Herbert Press.

- McQuiston, L. (1993). Graphic agitation: Social and political graphics since the sixties. London: Phaidon.

- Phillippe, R. (1980). Political graphics: Art as a weapon. New York: Abbeville.

- Schnapp, J. T. (2005). Revolutionary tides: The art of the political poster 1914–1989. Torino: Skira.

- Stone, M. S. (1998). The patron state: Culture and politics in fascist Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Taylor, P. M. (2003). Munitions of the mind: A history of propaganda from the ancient world to the present day. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Thompson, O. (1997). Easily led: A history of propaganda. Phoenix Mill: Sutton.