Symbols are linguistic devices in which complex, culturally specific meanings are communicated simply. Nearly all human utterance is in some ways symbolic, and for many who study communication, symbolizing is the most fundamental attribute of being human (Burke 1966). Peirce defines a symbol as “a sign which refers to the Object that it denotes by virtue of a law, usually an association of general ideas, which operates to cause the Symbol to be interpreted as referring to that Object” (1965, 143). In other words, when cultural conventions define how a sign is to be associated with an idea or object, then that sign is a symbol. Generally, the connection between signifier and signified in a symbol is arbitrary, necessitating a cultural context for understanding. Because nearly every image has symbolic aspects, symbols are especially important in the visual media.

As in the Magritte painting entitled Ceci n’est pas une Pipe, which depicts a pipe yet declares “this is not a pipe,” all communication stands in for something else: nothing is precisely equivalent to what it conveys. With symbols, a simple object represents something complex. Therefore, understanding how a symbol conveys meaning is essential to making sense of it. As Eliade states, symbols express “a complex system of coherent affirmations about the ultimate reality of things, a system that can be regarded as constituting a metaphysics. It is, however, essential to understand the deep meaning of all these symbols . . . in order to succeed in translating them into our habitual language” (1974, 3). For Jung (1980), a symbol is at once familiar and alien, an everyday, conventional use of language that is filled with connotations far beyond its denotative simplicity. In fact, the power of symbols is their ability to express complex concepts simply through “deep meaning” extraction.

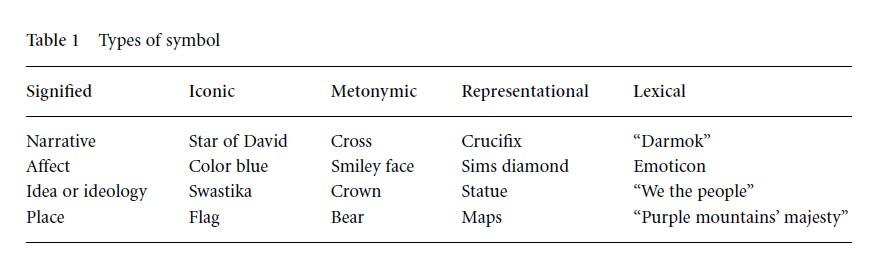

In semiotic terms, symbolism is a type of sign where the following conditions generally pertain: (1) the symbolic signifier is substantially different from the signified by type and domain; (2) the relationship between the symbolic signifier and signified is asserted, not natural or intrinsic; (3) a cultural code is needed to extract the signified from the signifier; (4) this signified is commonly a narrative, an affect, an idea or ideology, and/or a place – symbols often evoke many of these signifieds simultaneously; (5) the device of the symbolic signifier is metonymic, iconic, representational, or lexical – indexical signifiers are not generally associated with symbols except through the most basic level of symbolic embodiment, e.g., onomatopoeia, or through naturally occurring symbols, such as smoke denoting fire; (6) the symbolic signified is not otherwise easily represented; and (7) the symbolic sign is especially connotative, conjuring expansive meaning from a simple denotation.

Table 1 Types of symbol

Symbol Types

Symbols can be divided into various types based on the relationships between their signifiers and signifieds, as illustrated in Table 1.

Iconic symbols are those where the signifier has a strictly arbitrary relationship to the signified. An example of an iconic narrative symbol is the Star of David, a shape that conveys the history of a people that is not specifically a narrative element. An example of an iconic affect symbol is the color blue, meant to convey sadness, but unrelated to that mood. A swastika is an example of an iconic ideology symbol, intrinsically unrelated to the Nazi ideology it has come to signify, while a plus symbol (+) is a signifier of the idea of addition in mathematics. A flag is an iconic place signifier because its colors and pattern have no intrinsic relationship to what they represent.

Metonymic symbols are those where the signifiers embody a particular aspect or attribute of the signified, using that aspect to stand in for the whole. A cross, for example, is an element in the Christian crucifixion narrative that has come to stand in for all of that narrative. A yellow “smiley” is an indication of happiness that reduces the emotion to one indicator of it, a smile. An example of an ideological metonym is a crown, which is one thing worn by a monarch but signifies the monarchy. A bear is sometimes used as a metonymic symbol of Russia, though a bear is just one of many species found there. A sound can also serve as an iconic or metonymic symbol. For example, the ringing of a bell is an icon that can symbolize the serving of dinner, and the sound “hiss” is an onomatopoeic symbol for a snake that is also a metonym of the sound a snake makes.

Representational symbols are those where the signifiers illustrate narrative elements of the signified. Unlike a cross, a crucifix is an illustration of a part of the story in the Christian narrative, not merely an artifact within it. In the computer game “The Sims,” a rotating diamond levitates over the heads of the characters, symbolizing their mood: green means happy, red means miserable, and so on. A civic statue is often a representational symbol that embodies an idea or ideology, such as the golden statue of Kim Il-Sung in Pyong Yang. Maps are a representational symbol of place because the images on a map correspond to and illustrate geographic features.

Lexical symbols are those where words or sounds, rather than images, are used as signifiers. An episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation called “Darmok” illustrates lexical symbols. The human crew of a space ship encounters space aliens with whom they find it impossible to communicate. The alien captain keeps saying things that seem nonsensical to the humans, for example “Darmok and Jalad at Tenagra.” It turns out that these phrases are lexical symbols that refer to particular stories in the alien’s mythology. The whale MobyDick from Melville’s novel is an example of a particularly complex lexical symbol whose signifier has many signifieds. The whale can be seen as the embodiment of fruitless quests, Ahab’s madness, the greatest glory, a competing god, evil personified, or other signifieds. In a more simple way, phrases like “it was a dark and stormy evening” are used to represent emotions, phrases like “we the people” are used to represent ideologies, and phrases like “purple mountains’ majesty” are used to represent a place.

Decoding Symbols

For Peirce (1965), symbols find their origins in and evolve from indexical and iconic utterances, relying on complex interactions of sign systems known within a cultural context. As such, symbols are generally polysemic, which means they are open to divergent interpretations. The polysemic nature of symbols comes from their unique occurrence within their connectedness to the culture and to other symbols. For example, the swastika in Europe has a very different meaning than it does in India. This is in part because different users of the symbol use it differently. Saussure (1959) examined how symbols emerge from a language (langue) but iterate as a single utterance (parole) – each utterance relates back to the pre-existing language but also modifies and adds to it.

Hence, the pop singer Madonna’s use of a Christian crucifix in the music video “Like a Prayer” as a single utterance both relies on and inverts the symbol as found in the langue. Other uses of a crucifix are more conventional, yet still unique, utterances of the language of the crucifix symbol, such as a highly stylized crucifix that might be found in a modern church or the crucifixion scene in Salvador Dali’s painting Christ of Saint John of the Cross. To use Stuart Hall’s (1980) taxonomy of codes, Madonna’s might be considered an oppositional reading of the crucifix symbol, because it rejects the dominant understanding of its meaning; Dali’s painting is an example of a negotiated reading of the symbol because it modifies it into a different context; and the hanging of the crucifix in a church is an example of a hegemonic reading, because it reinforces the dominant sense of its meaning.

The Tibetan Buddhist mandala is an example of a symbol where the correct cultural code, and therefore a prescribed manner of decoding, becomes essential. Over a period of many days, Tibetan monks construct an elaborate depiction of the cosmos out of brightly colored sand, one grain at a time. Upon its completion, the ornate mandala symbol is ceremonially swept away to become a pile of brown dust. To western observers, whose system of symbols and myths prizes eternality, this gesture of destruction can be perplexing and meaningless, because of the destruction of a time-consuming work of art. To Buddhists, the destruction of the mandala is inextricably part of the mandala, because it symbolizes the temporal nature of existence: nothing, not even the cosmos, is permanent.

Symbols In Context

The specificity of meaning of a symbol varies with its level of analysis. Morris (1970) divides the way signs are understood into three categories: semantics, which examines the relationship between a signifier and what it signifies; syntactics, which examines the relationship between signs in formal structures; and pragmatics, which examines the relationship of signs to those who interpret them. Applying this to symbolism, the semantics of symbols relate to how they are constructed within a cultural context, the syntactics of symbols relate to how they are used linguistically, and the pragmatics of symbols relate to how symbols are understood. Put another way, cultures create genres of symbols, artists and authors create linguistic uses of symbols, and readers create interpretations of symbols. Therefore, genre theory, auteur theory, and reception theory are all useful approaches to understanding how symbols function.

Substantial literature exists in two of these three domains. Anthropological and psychological approaches focus primarily on the cultural role of symbols. Literary and artistic approaches focus primarily on interpreting symbols created by individual artists and authors. The communication field has done more work on reader responses to symbolism than most other fields, and there are numerous examples of symbolic meaning being created by users. Examples include the symbolism of Paul McCartney’s alleged demise found on the Abbey Road album cover, of drug use found in the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” and of patriotism found in the Bruce Springsteen album Born in the USA, all of them connotations unintended by the creators.

Symbols serve such a profound sense-making function that there has been some theoretical discussion of whether symbols are “hard-wired” into the communication circuits in the human brain. Cognitive scientists such as Steven Pinker have argued, for example, that human intelligence is a product of the ability to manipulate symbols (Pinker & Mehler 1988). Through their ability to create abstractions and store meaning in simple ways, symbols certainly serve an important cognitive function, leading Condit (2004) to suggest that both biological and textual approaches are needed to understand symbols as communication.

References:

- Burke, K. (1966). Definition of man: Symbols as a symbolic action. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Condit, C. (2004). How should we study the symbolizing animal? The Carroll C. Arnold Distinguished Lecture. National Communication Association, November.

- Eliade, M. (1958). Rites and symbols of initiation. New York: Harper Colophon.

- Eliade, M. (1974). The myth of the eternal return. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (eds.), Culture, media, language. London: Hutchinson, pp. 128–138.

- Jung, C. (1980). The archetypes and the collective unconscious, 2nd edn. (trans. R. Hull). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Morris, C. W. (1970). Foundations of the theory of signs. Chicago: Chicago University Press. (Original work published 1938).

- Peirce, C. (1965). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Vol. 2 (eds. C. Hartshorne & P. Weiss). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Pinker, S., & Mehler, J. (eds.) (1988). Connections and symbols. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Saussure, F. de (1959). Course in general linguistics (eds. C. Bally & A. Reidlinger, trans. W. Baskin). New York: Philosophical Library.