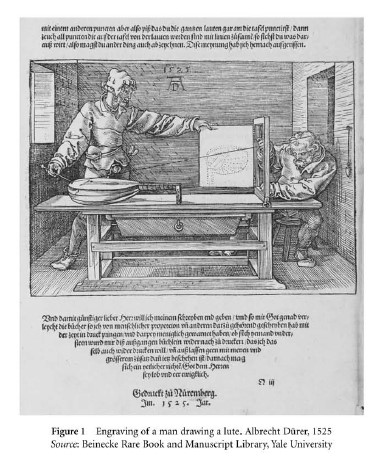

Perspective refers to the graphic representation on a flat surface of an optical sense of depth associated with natural stereoscopic vision. This translation of three-dimensional visual perception onto a two-dimensional picture plane is accomplished through a variety of techniques for composing the pictorial space, including: (1) diminishing scale, (2) the occlusion of figures and shapes, (3) atmospheric blurring or color variation from foreground to background, and (4) the converging of parallel lines at vanishing points along an imaginary horizon line. From the fifteenth century in Europe, artists increasingly used a combination of such techniques to create formal systems of perspective designed to present the picture plane as a kind of window, through which one views a visible world implied beyond the plane of the picture frame. Tied to the notion that a picture could, and should, imitate natural appearances, European drawing, painting, and print-making following the Renaissance conventionally organized the lines, shapes, and colors of the picture plane to appear to proceed outward from an observer’s unique point of view. The viewer sees depicted objects and space from the single perspective of the viewer’s unique position, as if the visible world was unified along the sight lines of this imagined observer. The representation of vision is stable and monocular. The point of view of the painter coincides with the beholder. Although recent polemical analyses have suggested that mirrors and lenses could have been used to produce the impression of perspective, Renaissance treatises advanced a conception of vision that followed mathematical projections and geometrical deductions, as illustrated in Dürer’s engraving of a man drawing a lute (Fig. 1; Hockney 2001; ckney & Falco 2003; Neiva 2005).

Figure 1 Engraving a man drawing a lute, Albrecht Durer, 1525 Source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Lidrary, Yale University

Perspective does not represent human vision per se, but it represents one of the potential modes of representing vision. While Damisch (1987, 37) has criticized the temptation to consider the idea of perspective as a pictorial code, its self-referential visual nature as its regulative presence across western art may indicate otherwise. Goodman (1976) argues that the notational system of perspective relates closely to human language, constituting a conventional and symbolic code that requires cultural training to decipher. Some scholars of visual culture therefore contend that cultural learning is necessary to visual comprehension (Bryson et al. 1994).

Perspective – More Than A Conventional Code?

The notion that perspective is little more than a culturally conventionalized pictorial code, a kind of visual morphology of grammar of image – making, perspectiva artificialis (Goodman 1976), contrasts with the idea that renderings of linear and aerial perspective in art successfully mimic the perspective of natural perception, perspectiva naturalis (Messaris 1994). Humans as a species may experience natural perspective in routine vision, but pictorial techniques for rendering visual depth have not always been available to artists, painters, and architects, and the particular conventions of linear perspective that emerged in the western tradition of picture-making have not characterized the picture-making of numerous other cultures.

It is something of a paradox, then, that perspective be considered the pre-eminent device of realistic visual representation. In the process of seeing the natural world in perspective, the observer knows that the railway is constructed of parallel tracks, and that they remain parallel even when vision indicates that the parallels converge to a vanishing point on the horizon. Yet in attempting to represent this visual experience on a flat picture surface, the artist consciously plots lines that actually do converge, artificially foreshortening depth within practiced and self-contained schemes that have become, not only accepted norms, but demonstrations of competence. Depiction in perspective translates the properties of objects in terms of a canonical pictorial procedure. The pictorial rule of perspective demands that every object reflected in the picture surface should not suffer distortion, but that the orthogonal lines receding in the distance converge to a point vanishing in infinity whose position depends upon the spectator’s viewpoint: “A pyramid of visual rays joins the objects that are seen to beholder’s eyes” (White 1967, 121). Alberti’s Della pittura (1973, 1st pub. 1436) defines the picture as the planar section of the visual pyramid. The sense of depth is obtained because the objects diminish in direct proportion to the individual’s gaze.

While foreshortening of objects amounts to a pictorial technique not unknown in antiquity, in fact familiar to the ancient Greeks, it was only during the Renaissance in Europe that perspective, as a completely homogeneous conception of space, came to full realization. Furthermore, the knowledge of representing in perspective supplies the pictorial ground of modern photography. This, in turn, leads to the assertion that perspective dominates the visual canon not only in western art, but in the use of pictorial material in various mass media, extending its global reach.

Even if foreshortening is not the most natural and inevitable mode of spatial representation (Waisanen 2002), perspective is now everywhere: in the cinema, on television, in the pictures found in publications that we read, and even in the design of magazine pages, posters and websites. We carry mobile phones that photograph and transmit scenes according to conventions of perspective. The relative universality of the Internet confirms, through use of photographs, that perspective is a mode of representation transcending cultural barriers.

Pictorial Representation, Classical Culture, Rhetoric, And Truth

More than a mere technique of pictorial representation, perspective must be seen as a rhetorical device. In both perspective and rhetoric, representations disregard objective and absolute truth. In perspective, the viewer never perceives things as they are, but instead as they seem to be, in the same way that in a persuasive speech what matters is not truth but truth-likeness, at best the surface appearance of truth. As Gombrich (1993) asserts, the world may never look like an image, but an image can be made to look like the world.

Among ancient authors, Plato (c.427–347 bce) not only noticed but also assessed negatively the mimesis of the painter, who makes pictures that comply with the compositional method of perspective, comparing the artist to the rhetorical sophist. In the Republic (X, 595 b–c), Plato states most clearly what he considers the correct moral and logical stand: “we must not honor a man above truth.” Objective and eternal truth, on the one hand, and persuasion and perspective, on the other, are irreconcilable. Consider their contrast: perspective and rhetoric represent the transitory, while absolute truth is averse to change, since what changes is not yet true. As illusionists, conjurers, and producers of simulacra, painters and sophists disseminate phantasms of truth (Republic X, 538 b–c).

Despite Plato’s disapproval, apocryphal anecdotes reveal the endurance and the lure of illusionary pictorial techniques. In his Historia Naturalis [Natural History], Pliny describes the outcome of a competition between the most skilled painters of the time: Zeuxis and Parrhasius. Zeuxis depicts grapes so real that birds come to peck at them, while Parrhasius paints curtains so perfect that Zeuxis asks his competitor to open the drapes. Parrhasius wins the dispute, having duped a fellow artist. Vasari (1980, 1st pub. 1550) records another tale: Paolo Uccello stays months without leaving the house, probing into the secrets of perspective. When his wife urges him to go to bed, Uccello makes it intimate: “Che dolce cosa è questa prospettiva!” (“What a sweet thing is this perspective!”)

Perspective And Pictorial Representation In Culture And Nature

Although a naïve conception of perspective might describe it as a simple reflection of human vision, perspective is a visual construction of an essentially mental nature. An image in perspective embodies a system of cultural meanings, being much more than the joint work of the hand and the eye. This is Panofsky’s position in Perspective as symbolic form (1991, 1st pub. 1927). Panofsky contends that perspective, like any symbolic construction, is the linking of a mental concept, the signified, with a material mode of pictorial representation, the signifier, within a system of diacritical distinctions. Before choosing a geometrical or optical strategy of representation, the image-maker has to have prior conceptual guidance. To represent in perspective, the artist must accept that the natural space of the world is not a quilt of isolated scenes, but rather one unified space.

Developing Panofsky’s ideas further, Francastel (1951) points out that perspective is the dominant factor in the cultural creation of a new type of pictorial space. To raise the apse of the church of Santa Maria de Fiori, Brunelleschi (1377–1446) came to the conclusion that he could not use the traditional medieval methods of construction. Brunelleschi’s solution relied heavily on geometrical and mathematical planning; but in doing so, he also gave birth to a culturally revolutionary conception of space, both uniform and measurable. Brunelleschi’s final plan derives from the application of perspective. It was more than a novel architectural solution: the transformation of natural space into a geometric representation constituted an intellectual anticipation of modern scientific conceptions of nature, in which the material qualities of the natural world are rephrased in a geometrical and mathematical language. Brunelleschi’s artistic achievement forecasted Galileo’s Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (1953, 1st pub. 1632).

Although it is quite accurate that the origin and the discovery of the pictorial method of depicting in perspective is the product of specific historical developments, and therefore a cultural invention, this does not mean that perspective is purely and solely cultural. Cultural systems of perspective should be seen as historically specific manifestations of our biological legacy. Depth information results from stereopsis, in other words, from the fact that the eyes produce slightly different views of the natural world. After receiving such data, the brain assesses the perceptual disparities, interpreting them and thus producing inferentially the sense of depth. As brain cells are binocularly driven, and as this indicates a prior cerebral categorization, the conclusion should be that both perceptual and pictorial perspective are inferential processes. And if differences in retinal information are the basic anatomical condition for vision in depth, then the cultural invention of perspective can be seen as an attempt to reproduce similar inferential processes.

References:

- Alberti, L. B. (1973). On painting. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. (Original work published 1436).

- Bryson, N., Holly, M. A., & Moxey, K. (eds.) (1994). Visual culture. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

- Damisch, H. (1987). L’origine de la perspective. Paris: Flammarion.

- Francastel, P. (1951). Peinture et societé. Lyon: Audin.

- Galilei, G. (1953). Dialogue concerning the two chief world systems, Ptolomaic and Copernician. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. (Original work published 1632).

- Gombrich, E. H. (1993). Additional thoughts on perspective. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 51(1), 69.

- Goodman, N. (1976). Languages of art. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

- Hockney, D. (2001). Secret knowledge. New York: Viking.

- Hockney, D., & Falco, C. M. (2003). Optics at the dawn of the Renaissance. Technical digest, 87th annual meeting, Optical Society of America, Washington, DC.

- Messaris, P. (1994). Visual literacy: Image, mind, and reality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Panofsky, E. (1991). Perspective as symbolic form (trans. C. Wood). New York: Zone. (Original essay written 1924–1925, published 1927).

- Neiva, E. (2005). Eyes, mirror, light. Semiotica, 155(1/4), 281–320.

- Vasari, G. (1980). Le vite de’ più eccellenti architteti, pittore, et scultori. New York: Broude. (Original work published 1550).

- Waisanen, J. T. (2002). Thinking geometrically: Revisioning space for a multimodal world. New York: Peter Lang.

- White, J. (1967). The birth and rebirth of pictorial space. Boston: Boston Book and Art Shop.