When a descriptor becomes more than its immediate signified – the concept that it refers to directly – we begin to feel that there is something special, something rather unusual about it. Such a descriptor is “Bollywood.” The word refers to a film industry situated in Mumbai/Bombay (the slash here is important because without its colonial name, “Bollywood” cannot be generated).

Bollywood has such pervasive currency in just about every part of the world that even the Oxford English dictionary (2005) has an entry for it: “a name of the Indian popular film industry, based in Bombay. Origin 1970s. Blend of Bombay and Hollywood.” The OED acknowledges the strength of a film industry which in 2006 produced 152 films but which, since the coming of sound in 1931, has produced some 10,000 films. This figure is not to be confused with the number of films produced in India overall. The latter would take the total number to well beyond 50,000.

Economic Dimensions Of Bollywood

The numbers in all respects for Bollywood are quite staggering: a $3.5 billion per year industry which employs some 2.5 million people, ticket sales close to 4 billion every year, and a growing international market for the films. Films such as Salaam Namaste (2005), Veer-Zaara (2004), Kal Ho Na Ho (2003), Devdas (2002), and Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (2001) had box office collections of between $1.5 and $3 million in the US and between £1.5 and £2.5 million in the UK.

The short time span of these figures indicates the exponential demand for Bollywood in the UK and US Indian diaspora at the turn of the twenty-first century, even if India’s share in the global film industry, valued in 2004 at $200 billion, was less than 0.2 percent (Thussu 2007). One would have expected better returns from the UK but even there the Bollywood market accounted for just 1.1 percent of gross box office receipts in 2004 (Thussu 2007). At the forefront has been Yash Raj Films, a film company which quite self-consciously feeds the diaspora with values which it feels will alleviate the diaspora’s unrelenting unhappiness for being untimely ripped from their homeland.

Additionally, the impact on cable and satellite television has also been enormous. B4U (a British Bollywood movie channel launched in London in 1999) is now available on eight satellites in more than 100 countries. With fanzines such as Cine blitz, Filmfare, Movie, and Stardust available globally online and in hard copy immediately after production, the Bollywood experience is growing into a worldwide phenomenon.

Developing The Bollywood Genre

Like any postcolonial form, Bollywood cinema dealt with big issues – the idea of the nation-state, communal harmony, justice – all rendered through a melodramatic genre which grew out of a combination of the sentimental European novel, the Indian epic traditions, Persian narratives, a fair bit of Shakespeare, and the influential Parsi theatre, the last of these a form which effectively created the dramatic genre which was to become Bollywood cinema. In this phase Bollywood was not unlike Hollywood as it reworked its base genre, created subtexts around its great actors (K. L. Saigal, Ashok Kumar, Dilip Kumar, Devanand, Raj Kapoor, Nargis, Madhubala, Meena Kumari), its auteurs (Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor, and Guru Dutt), and its film studios. Fanzines fed on all of these, and it could be said that with a few significant shifts – the arrival of the “angry young man” character of Amitabh Bachchan being one such rare shift – the form remained more or less intact. Indeed, from Devdas (1935) to Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Bollywood cinema was a single interconnected syntagm.

Then came a sudden redefinition not so much of the form itself (which continued to be melodrama) but its mode of production, consumption, circulation, and its effects. In the late 1980s a combination of disco dance and Michael Jackson (popularized a few years earlier by Mithun Chakraborty) was superimposed upon the old staple of Bombay popular film, the sentimental song, in films such as Ashiqui (1990) and Dil (1990). The year is important inasmuch as these films also mark a decisive shift in theme, moviemaking techniques, and implied spectator. Youth, in the form of Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan, Amir Khan, and Abhishek Bachchan (to name a few), returns to Bollywood with the same kind of excitement which had brought Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, and Devanand to cinema in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

But there had also been a major shift in the nature of capital – from the old manufacturingbased wealth (so well documented in Mani Ratnam’s recent film Guru [2007]) to a new kind of wealth, which moved swiftly via cyberspace. This wealth was also a virtual wealth made and unmade as well on the Internet. The postmodern Bollywood, where the old depth of language and dialogue (hallmarks of classic Bombay cinema as seen, for example, in the 1953 Parineeta) is replaced by a “technorealism” (seen in the remake of Parineeta [2006]) at the level of production and the “mise-en-scène,” became the marker of Indian modernity (Rajadhyaksha 2003). With a difference, though – this (post)modernity negotiated a new definition of the spectator and a new definition of the subject of cinema.

Audience Of Bollywood Films

At the level of spectator, the implied viewer was no longer made up primarily of HindiUrdu speaking Indian denizens and those in the Middle East or the old Indian plantation diasporas (Fiji, Trinidad, Guyana, Surinam, Mauritius, and the like) but included, in growing numbers, South East Asians and the people of the new Indian diaspora of late capital. The latter – the well-to-do Indian diasporas of the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia; rich but also uneasy in supposedly multicultural nation states and often unable to connect directly with these nation states’ own popular cultural forms – began to emerge as the target audience, while in India, too, the growth of a new middle class with disposable incomes created lifestyles seemingly similar to the Indian youths in the diaspora. Bollywood captures this new consuming class across national boundaries – again, with a difference though.

Bollywood has a remarkable mediating function, inasmuch as it relocates, re-presents, and repackages contemporary culture for re-consumption by the diaspora. The shift from Bollywood as a postcolonial form (aimed at defining the nation, its values, and so on) to Bollywood as a transnational form responding to a new consumer community, whether within India or in the diaspora, is now its fundamental characteristic. The hype around Bollywood, if not its global box office success, however limited, captures this trend. Expressions such as “Bollywood industry,” “Bollywood bonanza,” “Bollywood fix,” “Bollywood shakedown,” “Bollywood romp,” “Bollywood breaks,” “Bollywood dancing,” “Bollywood calendar,” “Bollywood experience,” “Bollywood culture,” and “Bollyweb” are now not uncommon. Indeed, Bollywood is a signifier of Indian modernity itself: Aishwarya Rai, the current Queen of Bollywood, performs at the closing ceremony of the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, and the British television show Celebrity big brother (2007) suddenly becomes global news because of racial slurs made against its Bollywood star Shilpa Shetty by her housemates in the show.

The New Bollywood

Implicit in the Lloyd Webber–A. R. Rahman musical Bombay dreams is a whole new definition of the subject of the Bollywood film. The basic themes of love, desire, and separation, of the lure of the city and its material benefits, of the stability of the family are all there, but these are being slowly transformed at the level of discourse and at the level of representation. At the level of discourse, languages proliferate – Punjabi and English (as in Kal Ho Na Ho and Dhoom 2 [2006]), regional dialects (as in Omkara [2006]), Bombay slang (as in Lage Raho Munnabhai [2006]) – the English word “love” replaces its Urdu-Hindi equivalents; at the level of representation, the old “Bombay realism” is being replaced by a distinctly Bollywood “technorealism” and this distinctiveness is readily obvious in films such as Don (2006; a remake of the original Amitabh Bachchan Don of 1978) and Dhoom 2, where Bangalore software seems to overtake the camera. There is another distinctiveness, and this is in the two recent adaptations of Shakespeare: Maqbool (2006, based on Macbeth) and Omkara (2006, based on Othello). In both of these Shakespeare is modernized in very Indian ways; in Omkara with the use of Indian dialects; in Maqbool with its subtext of the Bollywood film industry itself.

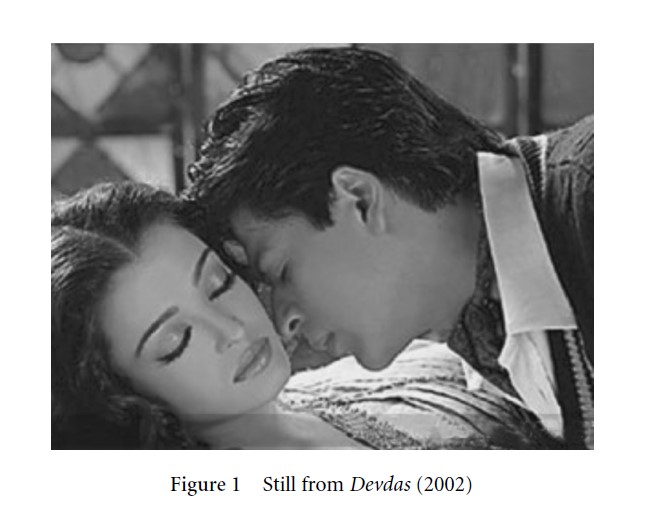

The argument about Bollywood as a “hype” and in its late modern form as a new “technoreality” comes together graphically in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s 2003 version of the P. C. Barua/Bimal Roy classic Devdas (1935/1955) based on Saratchandra Chattopadhyay’s 1917 sentimental novel in Bengali of that title. In Bhansali’s high-tech version of the film, the homage is neither to the writer of the novel nor to P. C. Barua and Bimal Roy (as the credits in the film declare) but to “Bollywood,” which now takes over Devdas and models it in its new image; the cinematic fidelity is not to an earlier form but to the film’s own postmodern, simulacral modes of representation. Where classic Bollywood cinema (the pre-postmodern variety) indicated an impossible love through lyric and metaphor, the new Devdas shows the suffering Paro holding on to an everlasting flame to signify her equally tragic love for Devdas (Fig. 1). Sentimental melodrama (the dominant form of Indian cinema) remains intact but its representation and effects have been radically altered.

Figure 1 Still from Devdas (2002)

With all the claims of globalization and transnationality, Bollywood remains different, and largely inaccessible, in its totality, to people not immersed in its form. In spite of all the borrowings from Hollywood (storyline, music, mise-en-scènes), Bollywood is the late modern face of India and of the Indian diaspora (Mishra 2002). For, in the end, it tries to be modern without throwing away its grounding in rather ancient ways of doing things (seen as late as 2006 in the film Babul), and these ways will always insinuate a different, an Indian, splitting of reason.

References:

- Dwyer, R., & Patel, D. (2002). Cinema India: The visual culture of Hindi film. London: Reaktion.

- Gopinath, G. (2005). Impossible desires: Queer diasporas and South Asian public cultures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Kavoori, A. P., & Punathambekar, A. (eds.) (2007). Mapping Bollywood. New York: New York University Press.

- Mishra, V. (2002). Bollywood cinema: Temples of desire. New York: Routledge.

- Prasad, M. M. (1998). Ideology of the Hindi film: A historical construction. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Rajadhyaksha, A. (2003). The “Bollywoodization” of the Indian cinema: Cultural nationalism in a global arena. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 4(1), 25 –39.

- Rajadhyaksha, A., & Willemen, P. (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Thussu, D. K. (2007). The globalization of “Bollywood”: The hype and the hope. In A. P. Kavoori & A. Punathambekar (eds.), Mapping Bollywood. New York: New York University Press.