In logic, validity is an attribute of the form of an argument that cannot lead from true premises to false conclusions. For example, “all A are B; some A are C; therefore some B are C” is a valid form. A common way to evaluate the validity of arguments is by treating it as a function of truth values – true or false – making sure that of all combinations of truth values, no false conclusions follow from true premises. In everyday life, the word “validity” is used similarly to “logic,” but more loosely and with qualifications. Nearsynonyms of validity are “soundness,” as in sound or unquestionable arguments; “plausibility,” as in conclusions that make sense and are accepted as most likely true; or “persuasiveness,” as in a convincing, believable, or credible account. Claims of validity are always built on a sense of authority, usually scientific, but also legal and popular. These synonyms can shift the burden of proof from the quality of arguments (soundness) to a community of reasonable people (persuasiveness), or to individual judgments (plausibility).

In the social sciences, and in empirical research in particular, researchers go out of their way to justify their findings in terms of how they came to them. The analytical methods they employ to proceed from data to findings are analogous to the arguments by which logicians proceed from premises to conclusions. By definition, data are unquestionable facts, hence true – save for the possibility of being unreliable. Scientific methods are designed to preserve the truths of the original data in the findings to which they lead. Because social research – unlike logic – theorizes diverse and often statistical phenomena, validity must here embrace probabilities and contexts. In the social sciences, therefore, validity refers to the quality of research leading to conclusions that are true to a degree better than chance and in the context in which they are claimed to be true. In the particular case of measurement, the validity of a test is the degree to which it measures what it claims it measures. Reference to chance and degrees of truth implicates probabilistic considerations, and references to claims contextualize the research process.

It is important not to confuse validity and reliability. Reliability concerns the trustworthiness of data. Data should represent only the phenomena of interest to the researchers. They should not be tainted by the irrelevant circumstances in which they were obtained, by interests in the research results, or by carelessly recording observations and measurements. Unreliability introduces uncertainty about what the data represent. It acknowledges that there is an above-zero probability of containing falsehoods. Because a method of analysis may well be invalid, perfectly reliable data do not guarantee valid conclusions. However, unreliable data always limit the chance for a valid method to produce valid findings. Just as it is important for logicians to know whether their premises are true, so it is important for researchers to know the extent to which their data are reliable.

Brief History Of Validity

Most social scientists use ways to demonstrate the validity of their research. At least since the 1940s, writers have proposed classifications of these practices and investigated their conclusiveness. Efforts to legitimize particular research methods culminated in a special scientific sub-discipline called “methodology.” The first effort to codify the terminology of validation efforts was undertaken by the American Psychological Association (APA; 1954), concerned with the validity of the then growing practice of psychological testing. This report defined four kinds of validity: content, construct, concurrent, and predictive validity.

Subsequently, the APA’s effort was joined by the American Educational Research Association (AERA) and the National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME; 1985). In a series of joint publications by these associations, terminologies emerged and were abandoned, showing no clear consensus. In 1999, the effort to standardize turned toward distinguishing the evidence that researchers use to support their findings (American Educational Research Association et al. 1999). Although some terms of earlier typologies migrated into sociology, political science, and economics, generalizations from psychological testing to truly social research proved difficult. For example, content analysis, a research technique for making valid and reliable inferences from texts to their contexts, bears little resemblance to aptitude tests for individuals.

Kinds Of Validity

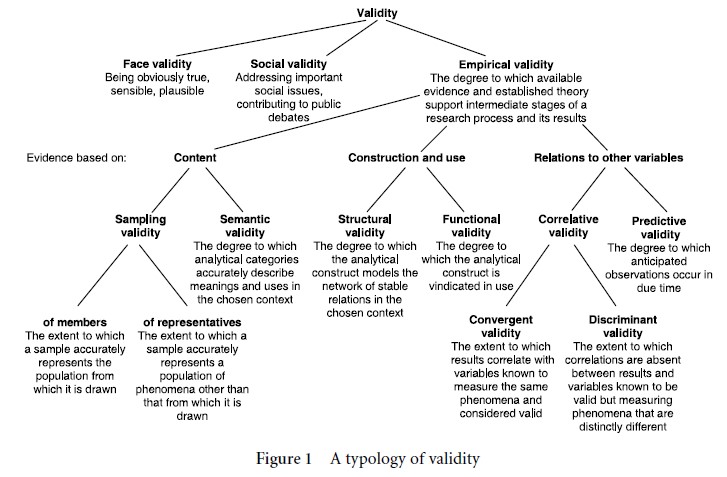

There are three kinds of validity to start with: face validity, social validity, and empirical validity. They justify the acceptance of research findings on different grounds.

Face validity is obvious or common truth. Researchers rely on face validity when they accept methods and results because they make sense, are plausible, or are persuasive, without feeling the need to give reasons for their judgment. Face validity is omnipresent in many decisions concerning scientific research. For example, findings that seem wrong or counterintuitive are not as likely published as findings that make sense. Face validity can be misleading, however. For example, it makes a lot of sense to take the relative frequency of mentioning a certain issue in the news as an indicator of how important that issue is to members of the public. Yet correlations between the two are notoriously weak. Face validity often overrides other forms of validity. Face validity results from individual judgments, although the cultural root of sense-making cannot be ignored.

Figure 1 A typology of validity

Social validity, also called pragmatic validity, is that quality of research methods and findings that leads one to accept them for their contribution to public debates or the resolution of important social issues: crime, terrorism, the antisocial behavior of juveniles, racism, lack in civility during political campaigns, etc. (Riffe et al. 1998). Justifying a particular research project almost always relies on social validity. Whether one evaluates its contribution to a group of scholars in pursuit of a theory, to a commercial sponsor, or to a research foundation, the criteria usually turn toward its usefulness, relevance, social significance, or impact. Scientific researchers may not acclaim social validity, but it generates valued public or peer-group support.

Empirical validity is the cherished concern of the sciences. It is the degree to which available evidence supports various stages of the research process, and the degree to which scientific conclusions withstand the challenges of additional data, other research efforts, and theory based on observations, experiments, or measurements. Campbell and Stanley (1963) call empirical validity “internal validity” and define it somewhat more loosely as the basic requirements for an experiment to be interpretable. Empirical validity cannot deny intuition (face validity), nor can it divorce itself entirely from social, political, and cultural factors (social validity) – after all, researchers are human and their work is reviewed by others, who may have their own theoretical commitments and personal alliances and are, hence, hardly immune to non-empirical concerns. However, the following typology, summarized in Figure 1, separates empirical validity from face and social validity by focusing on how empirical evidence is woven into the research process or brought to bear on its results.

Forms And Problems Of Empirical Validity

As already mentioned, most efforts to standardize validity concerns are rooted in experiences with psychological tests, only marginally addressing validity issues arising in content analysis, public opinion polling, communication research, and other social science methods. The following takes this point to heart and builds its typology on the distinctions among the kind of evidence used to support empirical research: content, construction and use, and relations to other variables.

Content refers to evidence that must be read or interpreted by individuals or organizations in order to be considered data. In the domain of psychological testing, Anastasi and Urbina (1997, 114) define content validity as “the systematic examination of the test content to determine whether it covers a representative sample of the behaviour domain to be measured.” It acknowledges the qualitative nature of written test items, text. Indeed, texts, which constitute most of the data in social research, cannot be treated in the same manner as meter readings. Even crime statistics, expressed in seemingly objective numbers, are developed primarily from narratives of people’s experiences or communications. To become a crime statistic, accounts of crimes tend to come in everyday terms that must be, first, understood and, second, analyzed, categorized, and counted. Evidence based on content naturally divides into two types: sampling validity and semantic validity.

Sampling validity is the degree to which a sample accurately represents the population of phenomena in whose place the sample is to be analyzed. One can sample from the members of a population, or from representatives of that population. Sampling theory provides various strategies to assure that the members of a population have an equal chance to be part of the sample. If a valid sampling plan is followed, the only uncertainty that remains is how large a sample must be to be representative of the population of interest. Unable to know the population in relevant variables without studying it, sampling theory relies on the law of large numbers, which suggests that the larger the size of a sample, the more likely it is that averages in the sample resemble those of the population. The law serves as validating evidence for a sample being representative of a population. The measure of statistical significance used in statistical tests plays the same role.

Sampling theory fails to address situations in which researchers are forced to select units for analysis from a source that hides, filters, or distorts the phenomena of the researcher’s interest. Therapeutic interviews, for instance, are conducted to aid a therapist’s treatment, not to uncover uncontaminated truths. They have to be interpreted accordingly. Similarly, unless mass communication researchers are interested in purely syntactical features of the media, they may have to be sensitive to the fact that its audiences, at least in the US, are not presented with what the outside world is like, but with what is easily obtainable and communicable, fits the editorial policies of the channel, attracts sponsoring advertisers, and holds audience attention.

Without direct access to the population of phenomena that they wish to study, researchers must treat the units they can sample for analysis no longer as members of a population but as representatives of that population. The method of selecting among such representatives must take into account how their source represents these phenomena and makes them available for analysis. Under such conditions, validating evidence concerns a data source’s selectivity, how these phenomena are presented. It justifies sampling methods that reverse the statistical biases of the source and guarantee that the sample actually analyzed represents the statistical properties of phenomena to be studied.

Semantic validity is the extent to which the categories of an analysis are commensurate with the categories of the object of inquiry. Kenneth Pike’s distinction between emic and etic categories is important here (Headland et al. 1990). The anthropological preference for emic or indigenous rather than etic or researcher-imposed categories of analysis demonstrates a concern for semantic validity. And ethnographers’ attempt to adjust their own accounts to their informers’ perceptions is an effort to gather evidence for the semantic validity of their findings. Traditional preference in psychology and sociology for abstract theory may not care about semantic validity. However, in public opinion research – asking questions that are relevant in the life of interviewees – and in content analysis – acknowledging how audiences interpret the texts being analyzed – lack of semantic validity spells trouble for the research results. They may say more about the researcher than about people’s opinions and audience receptions. Internet browsers are largely insensitive to the meanings of words and, lacking semantic validity, they often retrieve much irrelevant text.

Construction and use refers to evidence about the model characteristics that underlie a method of analysis – its algorithms and networks of analytical steps, or any parts of it. Earlier typologies defined construct validity as the degree to which a common pattern or theory underlies several measurements, until methodologists realized that all valid tests possess implicative structures – systems of relationships that imply each other – and are saturated with theoretical commitments. Evidence about the internal makeup or use of a method leads to two kinds of validity.

Structural validity is the degree to which a research method possesses implicit structures that demonstrably correspond to structures in the object of an analysis. Simulations, for example, will be structurally valid if it can be shown that they model the essential features of what they simulate. Psychological tests are structurally valid if they operationalize the psychological processes of the individuals tested. Evidence for structural validity may be obtained in the form of data about the composition and causal connections underlying the object of study, or previously substantiated theories about how the parts of that object work together.

Functional validity is the degree to which a method of analysis is vindicated by successful uses rather than validated by structural correspondences (Janis 1965). Because functions may be materialized variously, a research method may be functionally valid without being structurally valid. Demonstrating the functional validity of a method requires evidence in the form of a history of its successes and relative absence of failures – regardless of how that method came to its results. Taking a method’s successful and widespread use as a validity criterion can easily lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. For example, the use of college entrance tests, when instituted in a university’s admission process, becomes functionally validated by making it difficult for those who fail the test to prove themselves worthy of advanced education. In use, such a test creates its own truth.

Relating other variables to the results of a method of analysis has, again, two forms. Correlative validity is established by correlating the research results with variables that are concurrent with and extraneous to the way these results were obtained. The purpose of correlating research results with other variables is to confer validity on the otherwise uncertain research results. This transfer, however, can be accomplished only when the variables with which the research results correlate are known to be of unquestionable truth.

An important systematization of correlative validity is the multitrait-multimethod technique (Campbell & Fiske 1959). It calls for constructing a matrix of all correlations between variables that are related to measures of the phenomena of interest, including the research results to be validated, and a number of variables that concern unrelated phenomena. Comparisons among these correlations give rise to two kinds of validity, convergent and discriminant. For research findings to be correlationally valid, they must satisfy both.

Convergent validity is the degree to which research results correlate with other variables known to measure the same or closely related phenomena.

Discriminant validity is the degree to which research results are distinct from or unresponsive to unrelated phenomena and hence do not correlate with variables known to measure the latter.

For example, human intelligence is conceived of as underlying many extraordinary accomplishments in life. To have convergent validity, an intelligence test must correlate highly with all measures of phenomena that involve intelligence. To have discriminant validity, that test must be demonstrably independent of measures of phenomena that do not involve intelligence. If research results correlate with nearly everything, which easily happens when concepts are as pervasive as human intelligence is, correlational validity fails for lack of discrimination.

Predictive validity is the degree to which statements made about anticipated but unobserved and uncertain phenomena at one point in time are supported by evidence about their accuracy at later point in time. Pre-diction, literally “before saying,” is not limited to forecast, and not to be confused with generalizations from a sample to the population from which it was drawn. Moreover, correlations might suggest the predictability of recurrent phenomena, but they do not lend themselves to predictions. Predictions are validated by specifics, for example, by naming the actual author of an anonymously written text, correctly predicting a planned terrorist attack in at least some of its dimensions – perpetrators, time, place, target, and means of attack, or accurately forecasting stock market movements. When predictions are acted upon, their validity may surface in successes, for example in preventing a terrorist attack or gaining in the stock market.

References:

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education (1985). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education (1999). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (1954). Technical recommendations for psychological tests and diagnostic techniques. Psychological Bulletin Supplemental, 51(2), 200–254.

- Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing, 7th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitraitmultimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105.

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Headland, T. N., Pike, K. L., & Harris, M. (eds.) (1990). Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Janis, I. L. (1965). The problem of validating content analysis. In H. D. Lasswell, N. Leites, & associates (eds.), Language of politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 55–82.

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Riffe, D., Lacy, S., & Fico, F. G. (1998). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.