Commonly, people associate selling and advertising with marketing. In the old interpretation, this understanding of marketing was quite right, as marketing primarily comprised making a sale. But today, there is more to marketing than selling, promoting, advertising, and publicizing. Selling and advertising are only two of the many tasks of marketing management. Briefly, marketing is about “meeting needs profitably” (Kotler & Keller 2006). But although marketing can be summarized in such simple terms, there are many tasks behind it.

Today, marketing can be defined in the sense of market-oriented business leadership. This market orientation is characterized by all relevant activities and processes of the company that focus on consumers’ needs and wants (Esch et al. 2006). To focus on consumers and the market, it is one of the basic tasks of marketing to actually find out about relevant consumers’ needs and wants (Kotler 1967). Therefore, it is important to thoroughly analyze consumers. If marketers know consumers’ needs, the next step is to develop products and services that satisfy them (Drucker 1954).

The Scope Of Marketing In The Twenty-First Century

Marketers have to be very flexible, since markets are very dynamic. The management guru Peter Drucker (1954) once stated that a company’s winning formula for the last decade will probably be its undoing in the next decade. To be able to react to changes in the environment rapidly, it is important to permanently scan and monitor for signals of upcoming changes. In the twenty-first century, companies face changing customer values, which are observably getting more diverse. Even one and the same person can have different needs in different situations. The phenomenon of “hybrid consumption” is rapidly emerging. Firms try to react to specific needs by offering customized products. Obviously, this customization and segmentation leads to higher marketing costs and lower profit contributions of each brand and product.

Another challenge is increased global competition. In the wake of globalization and liberal markets, new competitors are penetrating the market. In particular, the liberalization of the Chinese market led to many new brands popping up. Also, western companies are trying to establish their products in new, attractive markets like China, with annual growth rates of about 10 percent (Pitsilis et al. 2004). This trend is intensified by new information and communication technologies like the Internet, which make it easier to sell products worldwide.

Along with a growing number of companies competing for customers, communicating activities have soared. Worldwide, there are more than 47,000 radio stations and 21,000 television stations (Lyman & Varian 2003). In addition, the Internet, events, sponsoring activities, product placement, and other types of below-the-line marketing are used to communicate with consumers.

For consumers, the world has become more complex, because of too much information pelting down on them. Due to limited capacities to process information, considering all alternative products would lead to an information overload. This trend is accompanied by products being outdated sooner (Lim & Tang 2006). In this environment, launching new products successfully is a real challenge. In 2002, around 27,000 new products were listed in food retailing stores in the USA. But after one year had passed, only half of those products were still on the market (Lim & Tang 2006).

Designing Marketing Strategies

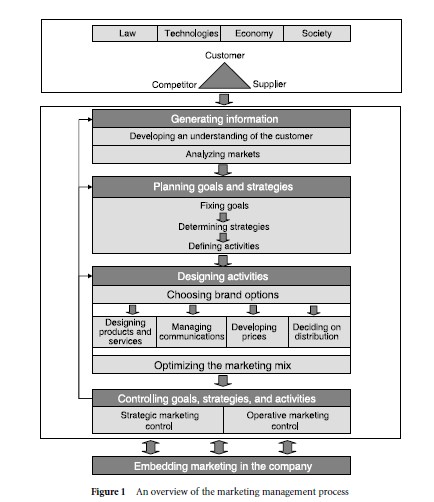

As markets become more complex and dynamic, systematic strategic planning is more critical than ever and marketing management becomes even more important (Ansoff 1965). A marketing plan, as the core of marketing management, is the central instrument for directing, synchronizing, and coordinating all marketing activities. Figure 1 gives an overview of the marketing management process, which can be defined as planning, coordinating, and controlling all market-directed activities of a company (Esch et al. 2006).

First, it is important for marketers to develop an understanding of their customers. Without a deeper understanding of consumers’ needs and wants, it is not possible to manage marketing successfully. Psychological processes in consumers’ minds and social processes between consumers and their environment need to be analyzed and understood. This analysis is the basis for influencing consumers’ decisions effectively. In a second step, information about the market needs to be generated, which means the general conditions of the market, the development of the market, and the company’s current and potential competitors. These market conditions are best detected, described, and explained by market research. Based on this information, marketing activities can be specifically designed and the success of activities taken can be controlled by gathering relevant data.

Based on this knowledge, goals and strategies must be determined. In this context, there are three levels that need to be planned systematically: (1) the marketing goal, which represents the situation strived for, (2) marketing strategies, i.e., the roads leading to that goal, and (3) marketing instruments necessary to “walk the road” (Esch et al. 2006). In a different determination, the first two levels are called “strategic marketing planning,” since they lay out long-term goals, and target markets and value propositions on the basis of the markets’ opportunities and threats. The lowest level represents the tactical side.

Figure 1 An overview of the marketing management process

Here, marketing tactics, like product features, communication strategy, or pricing, are specified. Therefore, it is important to synchronize different instruments to meet the challenges of the market in an optimal way (Kotler & Keller 2006). After defining the goals and strategy, activities must be designed that enable the company to reach its goals. The classic set of marketing activities is summarized by the 4Ps (product, price, placement, promotion), which are described in more detail below (McCarthy 1960).

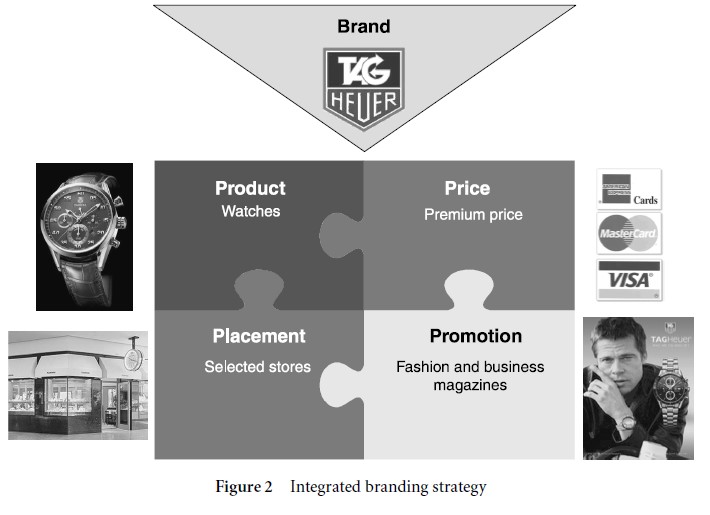

In our understanding, the 4Ps are the pillars of marketing, while branding is its base, on which all marketing activities are built. Therefore, it is crucial to base marketing strategies on a thoroughly planned branding strategy (Esch et al. 2006; see Fig. 2). These activities need to be thoroughly designed and synchronized, for the whole is more than the sum of its parts (Esch et al. 2006). To meet consumers’ needs, marketers need to adjust all instruments of the marketing mix to their target group (Borden 1964). They have to decide on what to sell, through which channels, at what price, and how they will give consumers information about the product and evoke a need for it.

Figure 2 Integrated branding strategy

To ensure that the activities taken help the company to achieve its goals, it is important to control activities, strategies, and goals regularly. Without monitoring their effectiveness, it is pointless to define goals. In this context, progress in the achievement of the company’s objectives has to be measured. Besides controlling the effectiveness of strategies and activities, marketers should revise whether the marketing goals are still worth striving for or whether they are outdated (Esch et al. 2006).

To manage marketing efficiently, marketing should be embedded in the company. This embedment in the company comprises the operational as well as the organizational structure of the company. The organizational structure must be designed in such a manner that it supports an optimal allocation of work, competencies, and responsibilities. The crucial point of this organizational structure is its orientation toward the products and brands of the company, the customers, and the relevant regions. In a complementary manner, the operational structure should be organized in a way that forwards processes to reach the marketing goals.

The Brand As The Base For Marketing Activities

Brands are central creators of value in companies, with which companies obtain extra price and quantity. Additionally, strong brands have a positive impact on all metrics of economic success. According to Interbrand (2007), Coca-Cola’s brand value amounts to 65.3 billion US dollars. Therefore, strong brands have notably high brand values (Esch 2007). About 67.0 percent of the corporate value is ascribable to the brand value (PricewaterhouseCoopers & Sattler 2006). In this respect, it is no wonder that brands are used to create value, e.g., by conquering new markets or groups of customers, by brand extensions, or by brand alliances. The aim of brand management is to build and sustain strong brands with high brand values (Esch 2007). Brand value can be defined from two points of view. First, the financial perspective defines brand value as the net present value of future discounted cash flows that can be obtained by the brand. This financial perspective refers to the economic success of the brand. Second, the consumer-based perspective describes brand value as the result of consumers’ reactions to marketing and branding activities in relation to identical activities taken by a fictitious brand due to consumers’ brand associations (Keller 2003). This view on brand value captures the reasons for a brand’s success.

A brand can be defined as a mental image in the minds of the target group that leads to identification and differentiation and affects people’s choices (Esch 2007). An example of a brand’s image affecting people’s behavior is Coca-Cola. Whereas in blind tasting, participants have a bias toward Pepsi, Coca-Cola is favored when the brand name is shown (de Chernatony 2001). Feelings like soulfulness or the “American way of life” that are commonly associated with Coca-Cola have an impact on consumers’ perception of taste. But creating a successful brand takes time and must be thoroughly planned.

Brand identity and brand positioning are the pivotal points for all brand decisions. In contrast to brand image, which refers to the perception of the brand, brand identity and positioning are in the company’s sphere of action. As the positioning of a brand is based on its identity, it is important to first determine a brand’s identity. Only exact knowledge of the brand’s central characteristics enables marketers to manage and design all marketing activities in conformity with the brand (Esch 2007). Brand identity expresses what the brand stands for. It captures those attributes that are essential and characteristic for the brand. These attributes of the brand comprise hard facts as well as soft facts like feelings and emotions. Moreover, attributes can be both verbal and nonverbal, e.g., consumers associate the “swoosh” with Nike, the “drumbones” with Intel, and the “contour bottle” with Coca-Cola. The aim of capturing a brand’s identity is to get a complete and holistic picture of the brand.

To create unique mental images in consumers’ minds, it is important to concentrate on only a few differentiating characteristics of the brand, which are captured by brand positioning. Positioning aims to create brands that are attractive to consumers and differentiate themselves from competitive brands in such a way that consumers are biased toward these brands (Esch 2007). Positioning therefore aims at clearly differentiating a company’s product from its competitors by linking the product with unique associations in consumers’ minds (Esch 2007). To successfully position a brand, it is important to focus on only a few attributes that differentiate the brand from its competitors (points of difference). Other attributes need not be better than those of competitors (points of parity).

Strategic brand decisions are on the agenda when companies consider branding new or newly acquired products and when existing brand systems need to be restructured (Esch 2007). Principally, companies face three basic options to lead their brands: (1) product brands, (2) family brands, and (3) corporate brands. Using a product brand strategy, every product of a company forms an own-brand; this means “one brand = one product = one brand promise” (e.g., Procter and Gamble, with brands like Pringles, Ariel, and Pampers). This strategy is favorable if the array of products is heterogeneous and aims at diverse target groups. By using different brands, each product brand can be tailor-made for its target group. But this obviously leads to high costs, as there are no synergies between the brands.

A family brand comprises several products under one brand, e.g., Maggi or Nivea. The advantage of this strategy is that all offerings of a brand profit from its existing brand image. As the range of products offered under one brand is relatively homogeneous, it is still possible to pointedly position a brand. Additionally, synergies can be exploited as marketing costs are born by several products. One of the major disadvantages of this strategy is the risk of distending the brand too much, when new products offered under the same brand no longer go with the identity of the brand.

Corporate brands are used for all products of a company. The prior aim of this strategy is to profile the company and its competencies. Corporate brands are advantageous if the range of products and services is too wide to employ product brands (e.g., General Electric), if the target groups and positioning of the offerings are relatively homogeneous (e.g., Allianz), and if the array of products undergoes fluctuations in short cycles (e.g., Armani).

The advantages of a corporate brand strategy are similar to those of family brands. Its disadvantages must be seen in the limited possibility to position the brand precisely and to fit it perfectly to its customers.

In practice, one scarcely finds these basic brand strategies in their classic form. Brand architecture describes the arrangement of a company’s brands for the determination of their positioning, and the relationships between brands and products from a strategic point of view (Aaker & Joachimsthaler 2000; Esch 2007). Brand architecture focuses mainly on the arrangement and the roles of two or more brands on different hierarchical levels to realize synergies by employing the corporate brand, while family and product brands still preserve a necessary degree of uniqueness. In this context, it is important to logically arrange brands and their relationships. The advantage of this strategy is the possibility to seize spillover effects. Brands on all hierarchical levels can benefit from the other brand’s image, if consumers perceive a relationship between these brands. The realization of the positioning idea requires integration of the various marketing instruments to build unique images in consumers’ minds (Esch 1998). Each instrument of the marketing mix leaves the consumer with a certain impression and influences the image of the brand (Lindquist 1974).

Raising Consumers’ Brand Awareness And Brand Image With Communication

To catch consumers’ attention for a brand and make them need it, its level of awareness must be raised. With communication activities, consumers’ attention can be revived and demand created. Additionally, communication is an effective instrument to build unique brand images in consumers’ minds. To communicate a brand’s image and to heighten its awareness, several instruments can be used, e.g., commercials and advertising, personal communication, promotion and publicizing, direct marketing, sponsoring, events and exhibitions, product placement, and guerilla and viral marketing. These instruments can be brought in line with the means of integrated communication.

Integrated communication is understood as the integration of form and content of all communication activities, which unifies and reinforces the impressions made. Through repetition of more or less identical impressions and information, the brand message is not only processed faster by the consumer, but the targeted image is imprinted in consumers’ minds. Communicating alternating and diverging impressions decelerates or even hinders learning processes. The perceived positioning of the brand is then far from its ideal. Finally, integrated communication saves costs, as the intended goals can be reached more effectively (Esch 2006).

In integrated communication, verbal as well as nonverbal elements can be used. These either transfer distinctive image associations (BMW is sporty and dynamic) or form an anchor to enhance brand awareness, for example, by using a particular color code (Orange uses orange dominantly in its communication) or symbols (Marlboro continually presents the cowboy). The first case is an example of semantic integration, the second of formal integration. Additionally, integrated marketing communication consists of integration over time and integration between different kinds of communication. In the first case, positioning contents of the brand need to be conveyed to continually realize learning effects and construct brand knowledge. If there is to be integration between different kinds of communication, it is necessary to translate the message and the means of integration into another kind of media.

To insure that the messages communicated are perceived, processed, and understood by consumers, communication must follow socio-technical principles. First of all, communication must succeed in contacting consumers to insure that the advertising message is perceived. Following that, emotions must be imparted and consumers’ understanding should be obtained. Finally, the advertising message is to be embedded in consumers’ minds.

Catching consumers’ attention is getting increasingly harder due to barriers of contact. Every day, consumers are confronted with an overload of information, which cannot be processed. Therefore, communication activities must be designed in such a way that they attract attention. This is possible by using activating stimuli that are physically intensive (e.g., loud colors and sounds), surprising (e.g., a person with the head of an animal), or emotional (e.g., the face of a child, a woman’s body). The use of these techniques depends on the recipient’s involvement, which can be defined as the degree of attention a person turns to a stimulus or an activity (Kroeber-Riel & Esch 2004). Especially in mass communication, recipients mostly have low involvement. Only consumers who are about to buy new goods and are actively searching for information are highly involved (Zaichowsky 1985). Generally, it must be stated that the lower the involvement of a person, the more activating the marketing communication should be (Kroeber-Riel & Esch 2004).

Frequency techniques aim at a frequent repetition of the communication message in one and the same communication medium as well as in different kinds of media. By this repetition, the likelihood that consumers have contact with the advertising message is raised.

Furthermore, marketers need to ensure that consumers process the advertising message. This includes factual as well as emotional information. Due to low involvement, consumers often interrupt contact with an ad after only a few seconds. A one-page ad in a magazine is looked at for approximately two seconds. To succeed in communicating the message, it is important to communicate information hierarchically as well as use pictures, as these are perceived, processed, and remembered easier and faster than verbal information.

Understanding a brand’s message is important for the success of the campaign, but should not be overestimated, as it only refers to direct processing of information. Moreover, consumers also process their own reactions and thoughts provoked by the ad. Emotions especially play a major role, as the emotional impression precedes understanding. Emotional communication can have two effects on consumers: (1) atmospheric effects, which influence the general ambience, and (2) emotional consumption experiences, through which a brand differentiates itself from its competitors. The aim of either effect is to generate acceptance of the product (Kroeber-Riel & Esch 2004).

As a basic principle, communication instruments can be divided into personal and mass communication. Personal communication refers to those communication instruments that allow interaction between two people. Due to this interaction, people can respond to their communication partner’s needs. In contrast to mass communication, personal communication is not only verbal through spoken and written language, but also nonverbal. People additionally get information from their communication partner’s mimics, gestures, tones of voice, or symbols used in the conversation. Mass communication addresses a large crowd of people. To diffuse information, mass media are used. Latterly, developments in mass media, such as the Internet, enable people to converse directly and respond to each other.

Regarding its impact on a single person, personal communication has an edge over mass communication. Personal communication distinguishes itself by greater credibility of the communicator, the possibility to respond to the listener’s needs, and the information conveyed by nonverbal communication. Moreover, personal communication offers higher flexibility. As the communicator can respond to the recipient’s queries, the recipient gets information that is tailor-made for his or her needs. In spite of these advantages, mass communication is prevalent. Because of its reach, mass communication can address more people in different places at the same time. Therefore, the costs per person addressed are as a rule lower than those of personal communication.

Regarding the buying cycle concept, neither of these two alternatives supersedes the other. The best strategy is to combine both kinds of communication. A customer’s buying cycle can be broken down into four different stages. The buying cycle starts when a consumer gets in touch with a product. This first contact happens through mass communication, e.g., through commercials on TV. These commercials often create demand for a certain product. Hence, in the second stage of the buying cycle, the consumer starts gathering more information. In this stage, personal communication is very important. Due to higher credibility, potential customers are more easily convinced to buy the product. Additionally, mass media can be used to offer detailed information in special-interest magazines. When a customer is finally buying a product, personal communication is essential. The assistant should give advice about special features and different models of the product. After the customer has bought the product, many companies are of the opinion that their business is finished. But quite the contrary, while the customer is using the product, a company should stay in touch with the customer. Brochures, events, or telephone calls by the company help the company to get feedback about its product and services. Moreover, the company knows in time if the customer is planning to replace the product. By providing him or her with information about new versions, companies can succeed in creating demand for a new product. If the customer is appropriately accompanied in this stage of using the product, it is very likely that he or she will also buy the new version from this company. If the company succeeds in satisfying its customer, the buying cycle starts anew.

Offering Benefits That Meet Consumers’ Needs

A company’s array of products complies with consumers’ actual and potential needs. Activities taken in this array can take four major forms. The aim of product variation is to deliberately change a product’s attributes or benefits, whereas its main benefits remain unchanged (Esch et al. 2006). Principally, product variation aims at modifying symbolic or aesthetic features, like design, color, or shape. By varying products, companies can meet changes in consumers’ needs and wants as well as adapt to changes in legal policies.

Product differentiation refers to adding further products that are modifications of existing products in the line. The reason for the popularity of this strategy lies in the possibility to meet each market’s specifics. But product differentiation can also bring cannibalization of company-owned products. Therefore, it is important to carefully examine the new product’s substitution effects in advance. A third option is product elimination. If products are outdated and are no longer successful on the market, it is best to eliminate them. Through this elimination, companies’ gain space on retailers’ shelves for new, successful products, though it must be considered whether the eliminated product is complementary to another product in the company’s line.

To ensure a company’s long-term success, product innovations play a pivotal role. Just recently, Nokia managed to raise its profits by 43 percent worldwide due to new products. A product innovation describes a company’s offering that consumers perceive to be a novelty and that differs widely from current products on the market. Before introducing a new product to the market, marketers need to thoroughly plan its communication, pricing, and distribution strategy.

Assessing Consumers’ Price Elasticity

The size of a company’s profits depends generally on its costs, its turnover, and the prices of its products and services. These three variables are interdependent. If a company sets a low price, its turnover goes up. As a rule, with higher turnover and higher production volumes, unit costs decrease. High turnover and lower production cost make it possible for companies to sell their products for a low price. But this strategy does not work out for all products and brands (Simon et al. 2006).

To find out what price leads to maximal profits, managers should estimate the demand and costs associated with the alternative prices and choose that price that leads to the highest estimated profits. There are many factors that affect a company’s cost and turnover functions; e.g., pricing has an effect on further variables, like competitors and their reactions, the product’s and brand’s image, as well as consumers’ reactions (Urbany et al. 2000). A major criterion that influences consumers’ acceptance of prices is their price elasticity. To assess the change in demand due to changes in prices, marketers need to know about consumers’ price sensitivity and price elasticity, which describe changes in demand due to a 1 percent rise in price.

In the first case, consumers’ price elasticity is relatively high, as an increase in price leads to a substantial decline in demand. Regarding the company’s profits, an increase in price cannot compensate the drop in sales. In the second case, it is quite the contrary. The same increase in price leads only to a small decrease in demand, as consumers are not very sensitive to changes in price. Therefore, the increase in price is likely to overcompensate the decline in demand, so that the company’s profits are liable to rise (Hanssen et al. 1990). Consumers’ price elasticity is low if there are hardly any substitutional products available or if consumers are reluctant to buy a different product. The second factor in particular can very well be influenced by companies. Due to customer relationship management and effective brand leadership, consumers’ loyalty can be increased and their price sensitivity lowered. Beyond that, brands offer additional benefits that justify higher prices from the consumers’ point of view.

But not all consumers are equally sensitive toward price. Even one and the same person perceives price differently dependent on the situation. For instance, people have a lower willingness to pay for beverages in a supermarket than in a restaurant. To seize these differences in price sensitivity, marketers should consider the instrument of price differentiation.

Price differentiation refers to selling principally the same products to different consumers or groups of consumers at different prices. The aim of this strategy is to skim as much as possible of the consumer surplus, which can be defined as the difference in consumers’ willingness to pay and the price actually paid.

As the willingness to pay differs between consumers, consumer surplus can be better skimmed by setting different prices for single consumers or groups of consumers. Pigou (1960) has identified three different forms of price differentiation. According to first-order differentiation, prices are set individually for each customer to perfectly skim his or her willingness to pay. Obviously, this strategy is not realizable in consumer markets. But in b2b markets, where a company addresses only a small number of potential buyers, custommade pricing is possible. Examples of second-order differentiation are airlines and theaters. Passengers decide for themselves whether they want to fly economy, business, or first class; theatergoers choose where they are seated. According to second-order differentiation, consumers decide independently to which price category they belong. By contrast, third-order differentiation does not enable consumers to choose their category themselves. Segments and the respective prices are pre-arranged by the company. Prevalently, consumers face this third-order price differentiation in cinemas or museums, where students, pupils, and pensioners typically pay lower admission fees. Another criterion for price differentiation is time of day. In some places, prices for telephone services or electricity are lower at night than they are during working hours. In practice, price discrimination often occurs relative to the amount bought by consumers. In this case, the overall sum is not linear to the number of units bought.

Another kind of price differentiation is price bundling, where the price of a bundle of mostly complementary products differs from the overall price of those products bought separately. The aim of this differentiation strategy is to better skim the consumer surplus of heterogeneous customers. Moreover, consumers are easily tempted to buy more than they originally wanted when products are offered in bundles.

To assess consumers’ reactions to changes in prices, it is important to analyze their price behavior, which generally comprises four aspects: interest in prices, knowledge of prices, functions of prices, and the evaluation of prices (Diller 2000; Esch et al. 2006).

Developing An Optimal Distribution Strategy

Planning a company’s distribution strategy involves all actions and decisions that need to be made to get the product to the customers. Establishing a distribution system takes several years, so it must be thoroughly planned as it cannot be changed abruptly (Esch et al. 2006). Distribution is an instrument of the marketing mix that is often underappreciated. But distribution is more than getting products to potential customers. A well-planned distribution strategy can support a brand’s image and evokes certain associations in consumers’ minds (Li Lam 2001). For example, luxury goods would no longer be strived for if they were obtainable everywhere. When planning their distribution strategy, marketers must decide on whether to sell their product directly or indirectly to the ultimate consumers, and whether their product should be distributed universally or selectively (Bowersox et al. 1980). Choosing a certain distribution strategy supports a company in addressing specific target groups and consistently communicating the positioning of the brand.

Companies that distribute their goods directly sell their products to the ultimate consumer without interposing any external distributors, like, for example, Avon with its salespeople or Body Shop with its own shops. Indirect distribution, on the other hand, takes place, if a distributor acts as an intermediary between company and ultimate consumer. Different kinds of indirect distribution exist on the market, which differ in the number of intermediaries involved. Supermarkets are often one-tier distribution systems, whereas pharmacies and florists are two-tier systems, consisting of retail and wholesale. A special form of indirect distribution is franchising, where a company’s products are distributed by legally and economically independent firms, whose relationship to the producing firm is agreed by contract. The franchiser (e.g., McDonald’s or Avis) provides the franchisee with procurement, retailing, and organization concepts against the payment of hires and shares of the franchisee’s sales.

One of the major disadvantages of intermediaries is the producer’s loss of control, i.e., how the products are presented in the stores. As the company does not have direct contact with the users of the product, it becomes harder to get information about their satisfaction with it. On the other hand, by using intermediaries, their distributor’s competencies and know-how of selling can be used, so that these tasks can be done more efficiently and more economically. From the consumers’ point of view intermediaries lead to more convenience. Stores where products of different brands and firms are sold make it easier for consumers to compare price and quality of the different products. Furthermore, if all brands contacted their potential customers directly, their information overload would be even higher (Coughlan et al. 2001).

Beside the number of tiers of the distribution system, marketers must decide on their selection of intermediaries. Companies can either distribute their goods universally or selectively. By choosing universal distribution, marketers pursue the target of their product being obtainable everywhere. It depends on the retailers whether they list the company’s products in their stores. This strategy is used especially for basic and everyday necessities. Furthermore, universal distribution is also favorable for goods with a low purchase risk and products that are often bought spontaneously. For these products it is important that consumers are often confronted with them.

If a producer carefully chooses the intermediaries that fit with their brand and their customers, the company follows a “selective distribution strategy.” Selection criteria, among others, are the size and business situation of the retailer, the quantity of units ordered, and the retailer’s service quality and promotion activities. For “exclusive distribution” the selection criteria are even stricter. This special case of selective distribution is prevalently paired with exclusive licenses in trading areas. Additionally, the cooperation is closer and conditions are well defined.

By distributing a product only via handpicked retailers, marketers try to ensure that the intermediaries do not oppose the company’s or the brand’s image. Moreover, although this approach secures the product’s presence on the market, it also ensures that it does not have the image of an ordinary, commonplace product.

To meet consumers’ benefits effectively and, therefore, to succeed in the market, marketers must not look at the instruments of the marketing mix as isolated tools. Quite the contrary; it is the interaction and orchestration of these instruments that make the company thrive. For instance, strong brands with a unique positioning are often distributed exclusively. In these exclusive stores, these products are available at a premium price. Besides, customers are attended to most attentively. They are offered additional services and are contacted regularly after their purchase. If marketers appropriately align all instruments of the marketing mix, the basis of the product’s success in the market is laid out.

References:

- Aaker, D., & Joachimsthaler, E. (2000). The brand relationship spectrum: The key to the brand architecture challenge. California Management Review, 42(4), 8 –23.

- Ansoff, H. I. (1965). Corporate strategy: An analytical approach to business policy for growth and expansion. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Borden, N. H. (1964). The concept of marketing-mix. Journal of Advertising Research, 4, 2 –7.

- Bowersox, D. J., Cooper, M. B., Lambert, D., & Taylor, D. A. (1980). Management in marketing channels. Auckland: McGraw-Hill.

- Coughlan, A. T., Anderson, E., Stern, L. W., & El-Ansary, A. I. (2001). Marketing channels. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- de Chernatony, L. (2001). From brand vision to brand evaluation: Strategically building and sustaining brands. Boston, MA: Butterworth Heinemann.

- Diller, H. (2000). Preispolitik. Stuttgart: Schaeffer-Poeschl.

- Drucker, P. F. (1954). The principles of management. New York: HarperCollins.

- Esch, F.-R. (1998). Brand image, positioning and service quality. European Journal for Sport Management, special issue on service quality, 82 –105.

- Esch, F.-R. (2006). Wirkungen integrierter Kommunikation. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitätsverlag.

- Esch, F.-R. (2007). Strategie und Technik der Markenführung. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

- Esch, F.-R., Hermann, A., & Sattler, H. (2006). Marketing. Eine managementorientierte Einführung. Munich: Vahlen.

- Hanssen, D. M., Parsons, L. J., & Schultz, R. L. (1990). Market response models: Econometric and time series analysis. Boston, MA: Kluwer.

- Interbrand (2007). Interbrand’s annual ranking of 100 of the world’s most valuable brands. At www.interbrand.com/best_brands_2007.asp, accessed July 20, 2007.

- Keller, K. L. (2003). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Kotler, P. (1967). Marketing management: Analysis, planning and control. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Kotler, P., & Armstrong, G. (2006). Marketing: An introduction. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2006). Marketing management. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Kroeber-Riel, W., & Esch, F.-R. (2004). Strategie und Technik der Werbung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. Li

- Lam, S. (2001). Exclusive or intensive distribution? The signaling role of channel intensity in consumer information processing. Advances in Consumer Research, 28, 204 –217.

- Lim, W. S., & Tang, C. S. (2006). Optimal product rollover strategies. European Journal of Operational Research, 174(2), 905 – 922.

- Lindquist, J. D. (1974). Meaning and image. Journal of Retailing, 50, 29 –38.

- Lyman, P., & Varian, H. R. (2003). How much information, 2003. At www.sims.berkeley.edu/howmuch-info-2003, accessed August 20, 2006.

- McCarthy, J. (1960). Basic marketing: A managerial approach. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

- Pigou, A. C. (1960). The economics of welfare. London: Macmillan.

- Pitsilis, E. V., Woetzel, J. R., & Wong, J. (2004). Checking China’s vital signs. McKinsey Quarterly, special issue, 7–15.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers, & Sattler, H. (2006). Praxis von Markenbewertung und Markenmanagement in deutschen Unternehmen. Frankfurt: PricewaterhouseCoopers. At www.markenlexikon.com/ d_texte/pwc_markenbewertung_01_2006.pdf, accessed September 17, 2007.

- Simon, H., Bilstein, F. F., & Luby, F. (2006). Manage for profit not for market share: A guide for profit in highly contested markets. Harvard, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Tellis, G. J. (1986). The price elasticity of selective demand: A meta-analysis of econometric models of sales. Journal of Marketing Research, 25, 331–341.

- Urbany, J. F., Dickson, P. R., & Sawyer, A. G. (2000). Insights into crossand within-store price search: Retailer estimates vs. consumer self-reports. Journal of Retailing, 76, 243 –257.

- Zaichowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341–352.