One of the most challenging tasks in research on media exposure is quantifying the amount of film viewing. Currently, people watch films via a variety of media, such as television, VCR, DVD player, computer and Internet, and cinema. For some of these media, it is difficult, if not impossible, to track the number of viewings. Especially when it comes to international comparisons, reliable numbers are often rare due to heterogeneous measurement systems. Nevertheless, we can obtain some valuable information from nonacademic sources about disparities in film exposure between different countries.

The Audience For Film In International Comparison

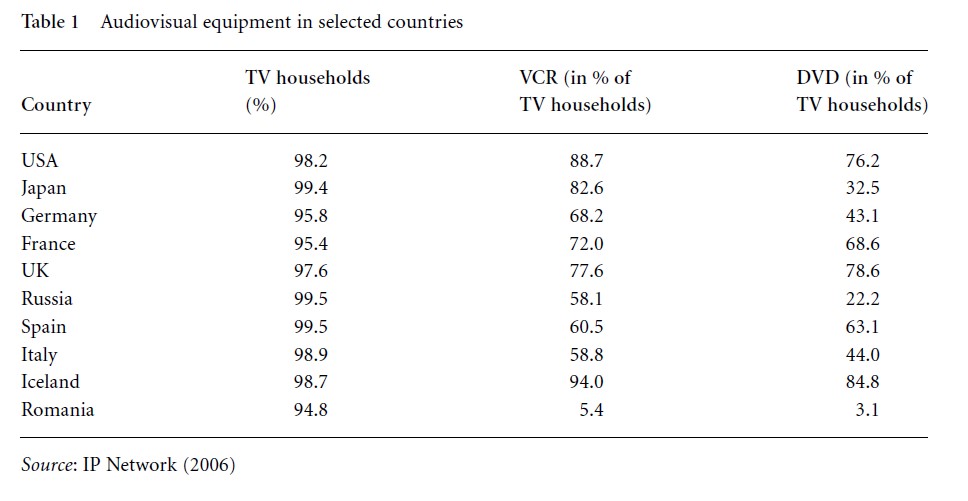

According to these data, even people from western industrialized countries vary in their amount of contact with films, as they differ in access to audiovisual equipment (Table 1) as well as in frequency of use of this equipment. Between 30 and 40 percent of TV viewing is dedicated to films, series, and other fictional narratives. Thus, the average time of exposure to film via TV in western industrialized countries can be estimated at between 60 and 100 minutes per day.

Table 1 Audiovisual equipment in selected countries

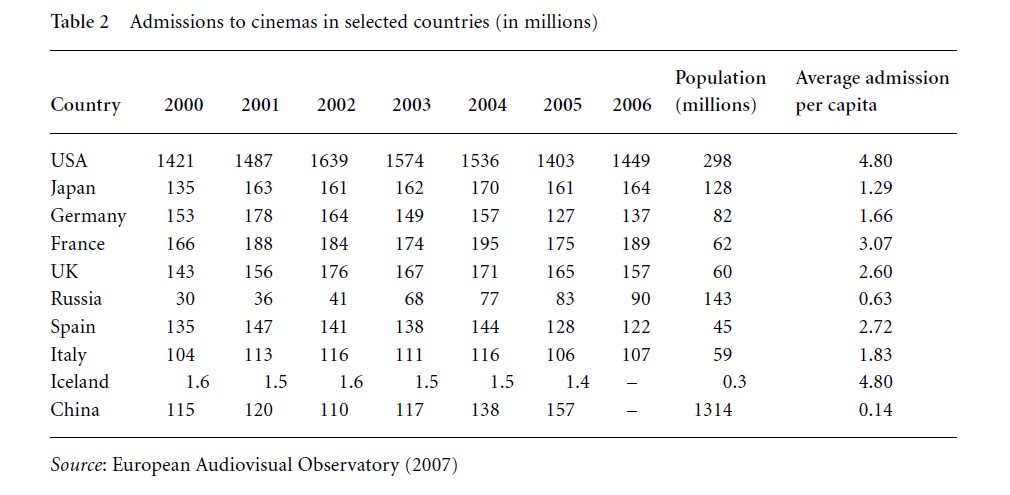

Table 2 Admissions to cinemas in selected countries (in millions)

Particularly with regard to cinema access and cinema visits, there is an enormous discrepancy between western industrialized countries (including Japan) and, for example, Russia or China. Every year, US citizens go to the movies almost as often as the rest of the world combined. On average, US citizens go to the movie theater 4.8 times per year, whereas Russians (0.63) and, even more notably, Chinese (0.14) go less than once a year (Table 2).

Psychological Reactions To The Exposure To Film

Overview

Films and movies belong to those prototypical media programs that can elicit emotional effects during exposure, which is explicitly reflected in the categorizing of many film genres, such as romance, erotica, thriller, horror, tearjerker, tragedy, drama, and comedy. Other sub-genres, like adventure, war film, science fiction, fantasy, pornography, mystery, and action film, evoke strong emotions during reception, too, because the stories generally are conceptualized with respect to the assumed psychological affect structures of the viewers (Bordwell 1985).

Although music is only an accessory to films, it can effectively influence the meaning of single frames, scenes, and the whole narration (Cohen 2001). Not only are specific sequences of the film interpreted differently depending on the music in the background, but the subsequent plot of a film can also be anticipated differently. Thus, music serves the film and fulfills dramatic, epic, structural, and persuasive functions.

The psychological processes that occur during film exposure encompass a wide range of different categories (Tan 1996; Plantinga & Smith 1999). Sympathy and empathy, excitation and arousal, suspense, fear, cognitive, and affective involvement, as well as joy and entertainment are key elements of most film genres. Tan (1995) proposed that interest is the central reception category in film viewing: “interest is the urge to watch and actively anticipate further developments in the expectation of a reward. The film’s control of the viewers’ perceptions of events imposes on them special attitudes towards those events and characters. The events themselves together with the attitudes coloring them determine the viewers’ emotions” (Tan 1995, 7). Additionally, Tan (1996) distinguishes emotions that arise from concerns related to the film as artifact (A emotions) from those emotions rooted in the fictional world and the concerns addressed by that world (F emotions). Moreover, some communication scholars discuss whether the viewers are only witnesses of the events in the film or whether they can partly or completely identify with the heroes of the film . The extent to which one’s own identity is given up during film exposure has a significant influence on the spectrum of cognitions and affects being experienced.

Suspense

One of the most central categories in film exposure (very often the reason/motive for film consumption) is suspense. Suspense has primarily been investigated in the context of semiotics-oriented film studies, cultural studies, and popular culture research. Across all disciplines, one can distinguish between psychological and text-oriented approaches (Vorderer et al. 1996; Plantinga & Smith 1999). While psychological approaches concentrate on the interplay of various cognitive and affective constructs within an individual, the text-oriented approaches (e.g., structural affect theory; Brewer 1996) have their starting point in the narrative structure of texts and stories. Integrative works on film exposure try to combine both, as it has become apparent that the relation between the film text and psychological effects is more complex than assumed so far (Tan 1996; Plantinga & Smith 1999).

All of these approaches primarily explain the formation of suspense, but do not really explain why viewers consciously expose themselves to suspenseful and even frightening films that involve strong negative arousal and inner conflicts. Based on the background of excitation transfer theory, it is plausible that the relief and euphoria of a happy ending are more positive the more suspenseful and “stressful” the film was. But how can the fascination with suspenseful and frightening plots be explained when they are not resolved by a happy ending (Weaver & Tamborini 1996)? For an explanation of this phenomenon, communication scholars have developed and adapted a number of reasonable approaches, such as sensation seeking, playing, meta-emotions, catharsis theory, or emotion regulation.

Fear

Especially for children, suspenseful and frightening films could have long-term effects (Weaver & Tamborini 1996; Cantor 2002). Researchers found that long-lasting states of anxiety after film exposure are not rare even among juveniles. And even college students report being nervous after viewing scary films, experiencing sleep trouble, avoiding exposure to other scary films, and being afraid to go into certain rooms of their own house (Cantor 2002). “The extent to which adults experience these lingering fears after media exposure suggests that something other than the willing suspension of disbelief occurs when audiences view horror films” (Sparks & Sparks 2000, 85).

With this background, it is remarkable that most parents are not aware of these effects on their children and underestimate how much time their children spend watching frightening films. However, children gradually develop a set of regulation strategies to deal with such films. Children at the age of 7 years or younger use behavioral strategies in almost every situation (87.5 percent) when they are confronted with scary media content, whereas children between 8 and 12 years of age choose such strategies in 66.7 percent of such cases, and children at the age of 13 and older choose behavioral strategies in only 42.3 percent of all scary media situations (Cantor 2002). As they grow older, children learn that cognitive strategies are often more effective in regulating negative affect in a sensitive and constructive way.

References:

- Bordwell, D. (1985). Narration in the fiction film. London: Methuen.

- Brewer, W. F. (1996). The nature of narrative suspense and the problem of rereading. In P. Vorderer, H. J. Wulff, & M. Friedrichsen (eds.), Suspense: Conceptualizations, theoretical analyses, and empirical explorations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 107–127.

- Cantor, J. (2002). Fright reactions to mass media. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 287–306.

- Cohen, A. J. (2001). Music as a source of emotion in film. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (eds.), Music and emotion: Theory and research. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 249 –272.

- European Audiovisual Observatory (2007). Focus 2007: World film market trends. Cannes: Marché du Film.

- IP Network (2006). Television 2006: International key facts. Paris: IP.

- Plantinga, C., & Smith, G. M. (eds.) (1999). Passionate views: Film, cognition, and emotion. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Sparks, G. G., & Sparks, C. W. (2000). Violence, mayhem, and horror. In D. Zillmann & P. Vorderer (eds.), Media entertainment: The psychology of its appeal. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 73 – 91.

- Tan, E. S. (1995). Film induced affect as a witness emotion. Poetics, 23, 7–32.

- Tan, E. S. (1996). Emotion and the structure of narrative film: Film as an emotion machine. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Vorderer, P., Wulff, H. J., & Friedrichsen, M. (eds.) (1996). Suspense: Conceptualizations, theoretical analyses, and empirical explorations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Weaver, J., & Tamborini, R. (eds.) (1996). Horror films: Current research on audience preferences and reactions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.