In the context of information seeking through mass media use, the concept of informational utility has been developed to predict which information items an individual will attend to and which will be ignored. The concept of utility of information emerged in the discussion about cognitive dissonance, and related predictions were corroborated in a few empirical investigations as early as the 1960s (e.g., Canon 1964; Freedman 1965). A more detailed elaboration of informational utility, though without specific empirical exploration, was provided by Atkin (1973). He suggested four domains of informational utility and conceptualized information to potentially meet needs of surveillance, performance, guidance, and reinforcement. Information needs were taken to result from uncertainties in how to respond to everyday environmental requirements. Thus, information is needed for adaptation to the environment, cognitive adaptation (surveillance), behavioral adaptation (performance), affective adaptation (guidance), and sometimes defensive adaptation (reinforcement). Cognitive adaptation (surveillance) has attracted most attention in subsequent research.

On surveillance as an informational utility facet, Atkin stated that the individual “maintains surveillance over potential changes that may require adaptive adjustments, monitoring threats or opportunities and forming cognitive orientations such as comprehension, expectations, and beliefs” (Atkin 1973, 212). More specific predictions on surveillance needs, as they may guide selective exposure to information, can be derived from a more detailed model of informational utility (e.g., Knobloch et al. 2003; most recently, Knobloch-Westerwick et al. 2005) that projects information relating to individuals’ immediate and prospective encounter of threats or opportunities to have utility for these individuals, the degree of which increases with (1) the perceived magnitude of challenges or gratifications, (2) the perceived likelihood of their materialization, (3) their perceived proximity in time or immediacy, and (4) their perceived efficacy to influence the suggested events or consequences. Hence, depending on the extent to which these dimensions characterize reported events, the news report carries utility for the recipient. The increased utility of messages, in turn, fosters longer exposure to information. Hence, it is the perceived utility of information that motivates exposure; low-utility material is passed over in favor of attention to material of higher utility. Drawing on the classic approach/avoidance dichotomy, these impacts are suggested for both negative and positive news reports, as information on both threats and opportunities should carry utility. (For comparisons of the informational utility model with other approaches, such as the elaboration likelihood model and other models and concepts such as salience, involvement, or relevance, see also Knobloch et al. 2002, 2003.)

An example may serve to illustrate these dimensions. (1) News about a new and deadly disease holds more utility than a message about an illness that causes just a minor indisposition because the former indicates consequences of higher magnitude. (2) If the disease spreads on the US east coast, related media messages have more utility for news consumers living on the east coast than for those living on the west coast, as their likelihood of being affected is higher. (3) If the disease is spreading very quickly, consequences of reported events evolve in the very near future, and being in the know has more instant value and thus higher utility due to this immediacy. (4) Options to prevent infection that are highly effective will suggest the information has higher utility than will indications that no prevention means are available. Whenever media messages feature high levels of these dimensions of informational utility, news consumers should be more prone to expose themselves to the information, as it carries higher utility for them and helps them to adapt to environmental requirements.

Related Concepts

Persuasion theories have also incorporated dimensions largely in line with elements of the informational utility model. Several persuasion researchers (most recently, Roskos-Ewoldsen et al. 2004) have included magnitude and likelihood dimensions in their model and also postulated efficacy as an additional dimension. For instance, Rogers (1975) suggested in his protection motivation theory that (1) probability of occurrence descriptions in a message lead to perceived susceptibility (parallel to the informational utility dimension of likelihood); (2) magnitude of noxiousness in the appeal produces perceived severity (magnitude); and (3) depictions of the effectiveness of the recommended response and characterizations of an individual’s ability to perform the recommended response result in perceived efficacy (efficacy) to cause cognitive mediation in processing fear appeals.

The dimensions in approaches related to protection motivation theory are in part parallel to the informational utility model. However, the former approach was formulated to predict the effects of persuasive messages on cognitive processes and, more importantly, on protection behavior, whereas the latter was formulated to predict selective exposure to media. Protection motivation theory (Rogers 1975) and related communication models such as the extended parallel process model imply that individuals’ perceived efficacy to combat a threat would result either in danger-control behavior to prevent risks when efficacy is high, or in fear-control behavior to deny risks when efficacy is low. Whereas this logic was initially applied to information processing, an extension to information seeking behavior appears highly appropriate: individuals’ perceived efficacy to combat a threat results either in seeking out further information about the risk, when efficacy is high, or in avoiding further information on the threat, when efficacy is low. In the former case, information may be construed as useful; in the latter, the same information may only seem distressing.

Predictions of selective exposure to information derived from the dimensions of this model have been supported by empirical evidence, as explained below. In these studies, selective exposure was operationalized as time spent on information, although selectivity has been discussed on various levels. This approach is in line with that of Atkin (1973, 209), who suggests that “amount of exposure [is] simply defined as number of messages and the length of exposure.”

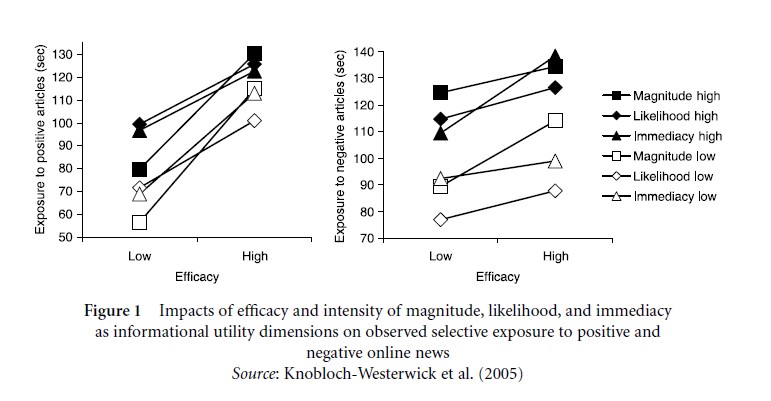

Figure 1 Impacts of efficacy and intensity of magnitude, likelihood, and immediacy as informational utility dimensions on observed selective exposure to positive and negative online news

Empirical Research

Two experiments (Knobloch et al. 2003) using negatively valenced stimuli supported the suggested impacts of the first three utility facets. These effects were also observed to be additive, as no interactions emerged. News readers indeed devoted more exposure time to negative news reports that were linked to higher levels of magnitude, of likelihood of being affected, and of immediacy of consequences of covered events than to articles featuring lower utility levels on these facets. Investigations by Knobloch et al. (2002) provided initial explorations into these informational utility dimensions as they impact selective exposure to positively valenced news. In these studies, German high-school students were to sample from either positive or negative reports that varied along utility dimensions. The findings demonstrated that likelihood and immediacy affected selective exposure to positive articles significantly, and magnitude and immediacy influenced self-guided exposure to negative articles. More recently, a cross-cultural experiment in the US and in Germany demonstrated the robustness of predictions derived from the informational utility model, as hypotheses about selective exposure to both positive and negative news were fully supported in both cultural settings (Knobloch-Westerwick 2005). Finally, Knobloch-Westerwick et al. (2005) corroborated the positive impact of higher efficacy as utility dimension for selective news exposure, both for positive and negative news and in interplay with the first three utility dimensions, as illustrated in Figure 1.

While selective exposure to information can be investigated on various levels (e.g., choosing between media consumption and alternative activities, choosing between different media channels), the summarized investigations looked at selections on the level of specific messages consisting of news reports. More specifically, selective exposure time was measured by software to serve as key dependent variable. As media users will oftentimes not be aware of their reasons for selecting some content while avoiding other messages and may furthermore not remember their selections correctly, observations of actual selection behavior are preferable in comparison to other measures to study selective exposure to information.

References:

- Atkin, C. K. (1973). Instrumental utilities and information seeking. In P. Clark (ed.), New models of communication research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, pp. 205 –242.

- Canon, L. K. (1964). Self-confidence and selective exposure to information. In L. Festinger (ed.), Conflict, decision, and dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, S. 83 – 95.

- Freedman, J. L. (1965). Confidence, utility, and selective exposure: A partial replication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2(5), 778 –780.

- Knobloch, S., Patzig, G., & Hastall, M. (2002). “Informational utility”: Einfluss von Nützlichkeit auf selektive Zuwendung zu negativen und positiven Online-Nachrichten [Informational utility: Impact of utility on selective exposure to negative and positive online news]. Medien-und Kommunikationswissenschaft, 50(3), 359 –375.

- Knobloch, S., Dillman Carpentier, F., & Zillmann, D. (2003). Effects of salience dimensions of informational utility on selective exposure to online news. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 80, 91–108.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Dillman Carpentier, F., Blumhoff, A., & Nickel, N. (2005). Informational utility effects on selective exposure to good and bad news: A cross-cultural investigation. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 82, 181–195.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Hastall, M. R. Grimmer, D., & Brück, J. (2005). “Informational utility”: Der Einfluss der Selbstwirksamkeit auf die selektive Zuwendung zu Nachrichten. Publizistik, 50(4), 462 – 474.

- Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of Psychology, 91, 93 –114.

- Roskos-Ewoldsen, D., Yu, H. J., & Rhodes, N. (2004). Fear appeal messages affect accessibility of attitudes toward the threat and adaptive behaviors. Communication Monographs, 71, 49 – 69.