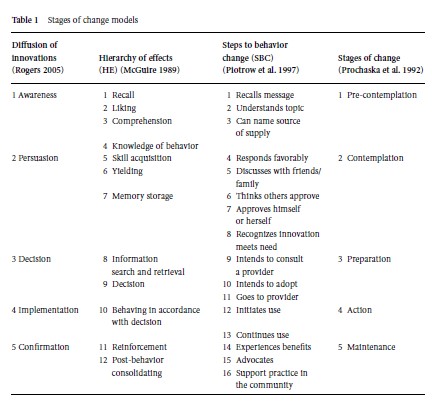

Some behaviors take a long time to change, and rarely do individuals progress immediately from awareness of a new product or idea to its use. Stages of change models document and specify the specific stages or steps a person goes through when they adopt or quit a behavior. At least four distinct stages of change models have been proposed: (1) diffusion of innovations (Rogers 2005); (2) hierarchy of effects (McGuire 1989); (3) steps to behavior change (Piotrow et al., 1997); and (4) transtheoretical model (Prochaska et al. 1992).

Diffusion of innovations is a theory that describes how new ideas, opinions, attitudes, and behaviors spread throughout a community (Rogers 2005). First developed by rural sociologists to study how farmers adopted new ideas, diffusion theory has grown into a robust science with applications in communications, health, marketing, sociology, and many other arenas. Diffusion theory has many components, one of which is that individuals pass through stages during the adoption process. These five stages were labeled: awareness, gaining knowledge of the new behavior; persuasion, learning more about it; decision, making a conscious decision to use it; implementation, first use and experimentation with it; and confirmation, continued use of the behavior (see Table 1).

The hierarchy of effects (HE) and steps to behavior change (SBC) models were developed as expansions of the diffusion stages by increasing the number of steps in the behavior change process and being explicit about the relationship between steps. The full hierarchy model consisted of a table in which the rows were the components of the Shannon and Weaver (1949) communication model (source, message, channel, receiver, and destination) and the columns were hierarchy steps (exposure, attention, comprehension, yielding, and behavior). The HE and SBC models are useful for three reasons: (1) they denote a more active audience in terms of information seeking and advocacy of the behavior, (2) they provide 12 or 16 specific, measurable steps in the behavior change process, and (3) the HE model proposed a rate at which individuals progressed through each step in the change process, advocating a model in which people could be expected to progress from step to step at a rate of 80 percent. Thus for a population exposed to a communication persuasion message, 80 percent of the population would progress through each step, with ultimately 6.9 percent experiencing the benefits of the new practice.

Stages of change and the transtheoretical model (Prochaska et al. 1992) also classified people into five stages: pre-contemplation, when they are not aware of the need to change behavior and do not intend to do it; contemplation, when they are aware of a problem but do not intend to change in the near future; preparation, when they intend to change their behavior in the near future; action, when they have made some behavioral modification; and maintenance, when they have made the behavior change for some period of time (usually six months or longer).

Table 1 Stages of change models

There are three distinctions between the stages of change and the diffusion or hierarchy stages. First, the diffusion or hierarchy stages were derived from studies designed to determine attributes associated with early or later adoption of new techniques, whereas the stages of change model was derived initially from studies intended to get people to quit smoking. The emphasis in stages of change was to understand how people quit a behavior (smoking), not adopt a new one. Second, the stages of change model measures cognitive states and shows how these change during adoption, whereas diffusion focuses more on how information sources and knowledge vary during adoption. Finally, diffusion has a much more extensive history and application than stages of change and so has been tested in multiple settings, but the stages of change model is used much more today and more extensively in the health field.

There are at least three reasons why stages (or steps) are used so frequently in communication research. First, they provide a way to group people, compare these groups on factors that affect behavior, and develop interventions targeted at specific stages. Second, progression between stages can be used as an outcome rather than relying exclusively on behavior. Third, change is not continuous, but rather marked by distinct events, steps, or stages that signify progression to adoption.

One main challenge facing stage models is to be consistent in their measurement, since stages may be calculated via recall or via change from baseline to follow-up. A second challenge is to determine whether individuals progress steadily through the behavioral change steps. For example, it may be that progression between earlier steps is more rapid than progression through later ones.

References:

- McGuire, W. J. (1989). Theoretical foundations of campaigns. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (eds.), Public communication campaigns. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, pp. 43–65.

- Piotrow, P. T., Kincaid, D. L., Rimon, J., & Rinehart, W. (1997). Health communication: Lessons for public health. New York: Praeger.

- Prochaska, J. O., Diclemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114.

- Rogers, E. M. (2005). Diffusion of innovations, 5th edn. New York: Free Press.

- Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical model theory of communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Valente, T. W. (2002). Evaluating health promotion programs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.