How has the spread of the Internet been studied and explained? Numerous studies have established that the spread of Internet access follows an S-shaped curve. What is not well understood is the factors responsible for different levels of Internet access among different countries. Many theories of the diffusion of innovations, such as the Bass model, are oriented toward individual factors, such as perceived need (Bass 1969). The inadequacy of this theoretical stance becomes readily apparent when we consider that cultures exhibiting low levels of gender empowerment deny Internet access to half of their populations. Thus, adoption of the Internet is affected by factors beyond simple exposure to the technology. What are the theoretical and methodological problems with the current approach to cross-country studies of the Internet diffusion process?

Cross-Country Research Design Issues

A common misconception, termed the pro-innovation bias, occurs when researchers assume that innovations, such as the Internet, will eventually be adopted by all members of a social system (Rogers & Shoemaker 1971). Related aspects of a pro-innovation bias concern attitudes that rapid diffusion is superior to slower diffusion and that innovations are not typically rejected. In reality, the degree to which innovations diffuse through a population is a complex function of many different factors, some of which act to impede the diffusion process. Part of the reason for the prevalence of the pro-innovation bias occurs because much of the diffusion literature exhibits a US and western European research focus. Data collection is expensive, and consequently data availability is higher in richer countries, which also happen to exhibit higher levels of adoption of new technology.

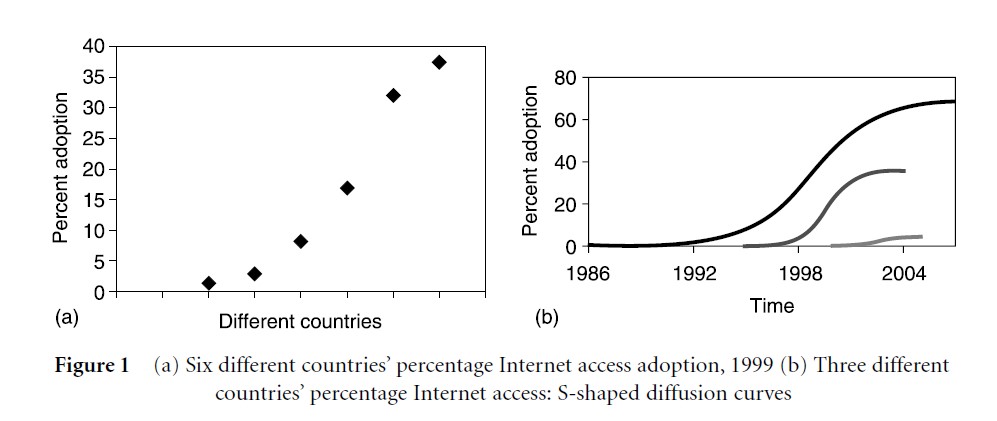

Pro-innovation biases are inadvertently created when researchers plot percent adoption of an innovation at a single time point, across multiple countries. The resultant curve is indeed often S-shaped (see, for example, Figure 1[a]), but it carries with it the implicit assumption that all of the plotted countries will follow a universal diffusion trajectory, and that, in time, countries at the lower left of the curve will eventually “catch up” with the countries on the top right of the curve.

Figure 1 (a) Six different countries’ percentage Internet access adoption, 1999 (b) Three different countries’ percentage Internet access: S-shaped diffusion curves

Figure 1(a) plots percent Internet access adoption for six countries for the year 1999; Figure 1(b) plots the full Internet access diffusion curves for three countries from 1986 through 2006. Clearly, these three countries are following very different Internet diffusion trajectories, a finding that is not apparent in Figure 1(a).

Another cross-country research design issue concerns the homogeneity assumption (Fforde 2005). Many studies use country summary data in multiple regression analyses. One of the primary underlying assumptions of multiple regression analyses is that the underlying population is homogeneous with respect to the pattern of associations (Cohen & Cohen 1983). In reference to Figure 1(b), are the factors responsible for Internet adoption the same for those three countries? The development of multiple regression models across non-homogeneous countries leads to misconceptions with respect to causal outcomes and applies a form of epistemological and ontological universalism that assumes people can be understood the same way, and are everywhere the same (Fforde 2005).

Cross-country sample selection issues abound in the literature. There are numerous examples of studies using “samples of convenience,” consisting of a relatively small number of countries. The problem here is that the results from these studies only generalize to that particular mix of countries. While these studies state generalization limitations in their discussion sections, the knowledge value of so many publications with limited generalization potential is questionable.

Country grouping effects are another area of concern. Clearly, different people find it convenient to divide the world in different ways. Grouping countries on the basis of their being on the same continent, a common practice, ignores the fact that there is a considerable degree of between-country variability within these global groupings.

Failure Of Theory

The Bass model (1969), developed in the marketing domain, provides an efficient mathematical description of the S-shaped diffusion pattern over time. The Bass model resembles epidemic models that describe the spread of a disease in a population through contact with infected individuals (Bailey 1957). In the Bass model, the concept of disease contagion has been replaced by the concept of a social communicative “contagion,” which is postulated to be chiefly responsible for the resultant S-shaped form of the diffusion process. Social contagion is defined as a spread of behavior from one individual to another, where one person serves as the stimulus for the imitative actions of another. The definition of the Bass model coefficients reflects the model’s connection with a social contagion explanation. The m parameter describes the market potential (the projected asymptotic level). The p parameter is interpreted as the coefficient of innovation because it presumably reflects the spontaneous individual rate of adoption in the population. The q parameter is interpreted as the coefficient of imitation because it presumably reflects the effects of prior cumulative adopters on subsequent adoption (Rogers 1995).

Defining a model’s fit parameters in terms of the influence of mass media and interpersonal communications from prior adopters presumes that communication processes in conjunction with individual decisions are chiefly responsible for the diffusion of innovations. But defining a model’s fit parameters in terms of speculative causal mechanisms is problematic. This raises the generalization issue known as construct validity. In this situation, do the Bass model’s p and q coefficients actually reflect the influence of mass media or interpersonal communication?

Non-Individual Factors Related To Internet Diffusion

Several researchers have suggested that the primary reason for cross-national inequalities in Internet access resides in differential economic development (Hargittai 1999; Rodriguez & Wilson 2000; Norris 2001; Chen & Wellman 2003). Findings that implicate public investment in human capital and infrastructure are important because they associate aspects of economic influence beyond the concept of GDP per capita with a country’s degree of Internet access. Increases in life expectancy and literacy require long-term investments in large-scale public services and facilities, such as public health, power, water, public transportation, telecommunications, roads, and schools. Aspects of wealth such as education and infrastructure take a considerable amount of time to develop and consequently policies designed to enhance Internet access through the insertion of short-term economic aid are questionable.

Norris (2001) considers individuals who prescribe to an economic interventionist policy as “cyber optimists.” In conjunction with short-term economic aid, a cyber optimist would expect Internet access to eventually defuse throughout a country’s population. This diffusion pattern (the “normalization” pattern) might be expected to occur in wealthy countries with cultures that value and reward innovative behavior. Alternatively, cyber pessimists would expect that, irrespective of economic aid, digital technology will more likely amplify existing inequalities of power, wealth, and education, creating deeper divisions between the advantaged and disadvantaged. This “stratification” pattern of Internet diffusion suggests that individuals who do adopt mostly consist of a country’s advantaged. Basically, Internet diffusion patterns that resemble the stratification pattern suggest that the individual’s ability to adopt is substantially moderated by country-specific cultural and economic considerations rather than the fulfillment of individual needs. Both adoption patterns yield S-shaped curves that can be fitted by mathematical formulations such as the Bass model. However, results similar to the stratification pattern are difficult to explain in terms of social contagion theory.

Given the normalization and stratification diffusion patterns, it is natural to question if the factors responsible for the diffusion of Internet access are amenable to “quick fix” treatments, such as the insertion of technology or short-term economic aid, or whether the degree of Internet access is shaped by more deep-seated forces, such as culture. Norris reports that affluent Middle Eastern countries have relatively low Internet access levels, a finding that raises concerns with the notion that, in all situations, economic factors are solely responsible for the degree of Internet access. Several Middle Eastern countries are wealthy and have been wealthy for some time, but aspects of their culture act to inhibit Internet access for half of their population, i.e., females. This is decidedly not a small effect and points to the danger of making generalizations when predictive factors are causally entangled. In that circumstance, a single correlation may yield a high degree of association, but the ability to predict something is not necessarily synonymous with understanding how something works.

A second point of consideration here is that explanations based on social contagion theory should work best in countries that support a normalization pattern of Internet adoption (i.e., the US and western European countries). In these countries, we would expect the adoption decision to be largely under an individual’s control. However, social contagion models should fail when attempting to predict Internet diffusion in countries that follow the stratification pattern of diffusion. When examined from this perspective, social contagion explanations for the diffusion of innovations appear to be an artifact of early diffusion research that predominantly focused on US and western European countries. These are the countries where the individual-oriented normalization diffusion pattern is found. These are the countries where the inhibiting effects of fear, diminished gender empowerment, and low levels of long-term economic development are minimized.

Clearly, social contagion theory provides an incomplete picture of the innovation diffusion process, and this theoretical deficiency naturally extends to explanations of that process based on definitions of the ubiquitous Bass model’s p and q coefficients. The implication is that models that seek to enhance understanding of the cross-country diffusion process need to utilize a mixed-level hierarchical modeling approach, where one level defines the moderating influence of country-specific factors and another level deals with individual decision factors.

References:

- Bailey, N. (1957). The mathematical theory of epidemics. London: Griffin.

- Bass, F. (1969). A new product growth model for consumer durables. Management Science, 15, 215–227.

- Chen, W., & Wellman, B. (2003). Charting and bridging digital divides: Comparing socio-economic, gender, life stage, and rural–urban Internet access and use in eight countries. The AMD Global Consumer Advisory Board. At www.amd.com/us-en/assets/content_type/DownloadableAssets/FINAL_REPORT_CHARTING_DIGI_DIVIDES.pdf, accessed January 11, 2007.

- Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Fforde, A. (2005). Persuasion: Reflections on economics, data and the “homogeneity assumption.” Journal of Economic Methodology, 12(1), 63 – 91.

- Hargittai, E. (1999). Weaving the western web: Explaining differences in Internet connectivity among OECD countries. Telecommunications Policy, 23(10/11), 701–718.

- Norris, P. (2001). Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodriguez, F., & Wilson, E. (2000). Are poor countries losing the information revolution? The World Bank infoDev working paper series. At www.infoDev.org/library/wilsonrodriguez.doc, accessed January 11, 2007.

- Rogers, E. (1995). Diffusion of innovations, 4th edn. New York: Free Press.

- Rogers, E., & Shoemaker, F. (1971). Communication of innovations: A cross-cultural approach. New York: Free Press.