Few concepts in the social sciences have attracted more attention and caused more confusion than the concept of the “public.” The dispute concerning the nature of the public is at least as old as Greek democracy. Since that time, one of the most divisive questions has been whether the public is characterized by an everyman, holding common opinions (doxa), or by an intellectual elite, endowed with deeper insight, knowledge, and wisdom (episteme). This controversy is the starting point for the following considerations. After a summary of different theoretical concepts, the relationship between the individual and the public is reviewed. The question of exposure to communication content is then addressed.

Since its beginnings in ancient times, the term “public” has bred a multiplicity of competing meanings (Habermas 1962; Childs 1965), which continue to shape scientific discourse today. Three major theoretical schools of thought can be identified: a normative or qualitative concept, an operationalist or quantitative concept, and a functionalist concept.

The normative or qualitative concept defines the public as a social elite comprising wellinformed, responsible, and interested citizens. These pursue the common good and participate in an enlightened and rational discourse on societal affairs. In a democratic system, the public forms a critical counterpart to the government, acting as an imaginary parliament and engaging in political deliberation. Moreover, the public discussion of political ideas and the free exchange of arguments are regarded as the heart of the democratic process, as they make the best, wisest solutions possible (Berelson 1952; Hennis 1957; Habermas 1962).

In the operationalist or quantitative concept, the public is regarded as a collective of diverse individuals whose views on a particular issue can be measured by opinion polls. According to this quantitative concept, the public is a certain cross-section of society, an “issue public,” as defined by survey research (Converse 1987). The functionalist concept defines the public as a system of social monitoring, enabling a society to observe itself and to react to issues which are or may become relevant to its members. The public has the function of monitoring trends and developments in society. It identifies and brings up important issues, reduces the complexity of social and political matters, and thus reaches a consensus on social conflicts (Luhmann 1970).

In addition, according to Noelle-Neumann (1993), the public can be understood as an institution of social control: its purpose is to enforce social conformity, stabilizing society as a whole. In contrast to the normative concept, in this view the public is concerned with political and nonpolitical issues, and includes not only the intellectual elite but every single individual within a social collective. Furthermore, the existence of the public is restricted neither to democratic systems nor to societies familiar with survey research or modern mass media.

The functionalist approach is the oldest concept: single thoughts, fragments of theory, and even comprehensive analyses can be found in every period of history (e.g., in the works of Cicero, Michel de Montaigne, or John Locke). In contrast, the normative concept did not emerge until the eve of modern democracies, during the age of Enlightenment in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Finally, the operationalist concept, which is closely connected to the advent of empirical social research, appeared in the first half of the twentieth century.

An examination of the public’s exposure to communication content must concentrate on the relationship between the individual and the public. The public is frequently viewed metaphorically as an organic being with a collective mind, yet this is an intangible generalization. Accordingly, all three concepts make statements about the relationship between the individual and the public. They share the view that the public consists of individuals who are both members of social groups and parts of specific media audiences. In the functionalist concept, these individuals, groups – including the elite – and audiences are pooled to form a single public. According to this understanding, the mass media are also social units and components of the public. Their function is to confer publicity, to set important issues on the public agenda, and to serve as a general communication forum and source of information for the public. The media give attention to specific topics and problems, thereby influencing public awareness of these issues. Additionally, their coverage serves as a frame of reference in public discourse.

The relationship between the individual and the public is determined by a mechanism of symbolic representation in the mind of every individual (Lippmann 1922; Mead 1934; Goffman 1963): virtually all people continuously form views of the public – it represents the generalized others in the individual’s imagination, even if nobody is physically present. As the individual’s perception or imagination of the public sentiment affects his or her own decisions (e.g., on voting) and opinions, it also contributes to the shaping of public opinion. Consequently, the public can also be defined as both a state of being exposed to others and an awareness of being (potentially) watched by the anonymous “public eye.” Individuals rely on two sources of information in order to assess public attitudes and behavior: interpersonal communication and the mass media (Noelle-Neumann 1993). Media statements regarding public sentiment pervade interpersonal communication along several steps of the flow of communication. In this manner, the media exert influence on the way the public is perceived; they shape the individual’s understanding of the proportion of opinions, i.e., of the size of minorities and majorities. Although individuals arrive in many cases at correct estimates of the opinion of others, erroneous judgments are possible.

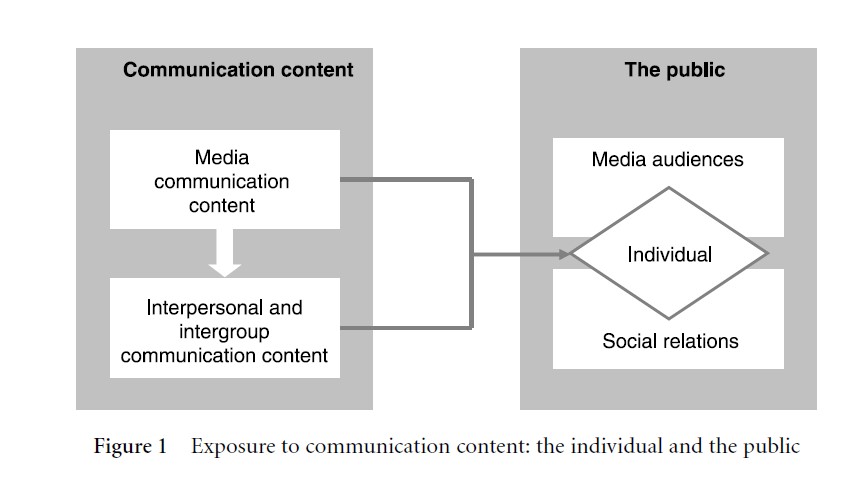

The circulation of communication content among the public takes place via intervening psychological and social processes: on the one hand, people’s exposure is framed by interpersonal relations; on the other hand, individuals expose themselves selectively to communication content, i.e., they actively seek information that is consonant with their initial attitudes and that is likely to satisfy their needs. Exposure thus varies according to personality and social factors. Members of the intellectual elite, for example, usually gain greater exposure to information content in the media than does the general population (Fig. 1).

In summary, it can be concluded that the public consists of individuals who seek exposure to communication content. This content derives either from interpersonal (intergroup) communication or from the mass media – which themselves in many cases influence interpersonal communication through their coverage. The public can be understood as a large collective of partially interconnected individuals, groups, and audiences through which (mass) communication is channeled.

Figure 1 Exposure to communication content: the individual and the public

References:

- Berelson, B. (1952). Democratic theory and public opinion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 16, 313–330.

- Childs, H. L. (1965). Public opinion: Nature, formation, and role. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Converse, P. E. (1987). Changing conceptions of public opinion in the political process. Public Opinion Quarterly, 51, 12–24.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in public places: Notes on the social organization of gatherings. New York: Free Press.

- Habermas, J. (1962). Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit: Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft [The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society]. Neuwied: Luchterhand.

- Hennis, W. (1957). Meinungsforschung und repräsentative Demokratie [Opinion polls and representative democracy]. Tübingen: Mohr.

- Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. New York: Macmillan.

- Luhmann, N. (1970). Öffentliche Meinung [Public opinion]. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 11, 2–28.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The spiral of silence: Public opinion – our social skin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.