Paralanguage refers to the nonverbal elements of speech – such as vocal pitch, intonation, and speaking tempo – that can be used to communicate attitudes, convey emotion, or modify meaning. In simple terms, paralanguage can be thought of as how something is said rather than what is said.

The study of paralanguage is known as “paralinguistics.” Early work on paralanguage emerged in the 1950s with the pioneering research of George Trager and Henry Lee Smith (Hall & Trager 1953; Trager 1958), who noted that kinesics (body movements) and vocalics (voice quality and other aspects of the voice) are part of the language system. Building on their work, other researchers focused on vocal pauses (hems, ahs, coughs), speaking rate, volume, and quality (Pittenger et al. 1960). Since that time, paralanguage has been studied and applied to numerous domains including psychiatry, child development, courtship, and deception.

The idea that how one says something may impact the meaning of what is said is a familiar concept. Most often, humans use paralanguage purposefully, though perhaps subconsciously, as many of these patterns have been learned since infancy. For example, when something is said sarcastically, the voice may take on a negative tone to accompany a positive word or phrase, or particular intonations may modify the meaning of the words that are spoken. The voice may also send messages and reveal information apart from the words. For example, emotions are signaled through the voice. When someone is aroused, the pitch and resonance of the individual’s voice change due to physiological changes in the vocal cords. Loudness may convey boisterous emotions; falling intonation may convey sadness or distress.

Factors Affecting Paralanguage

There are many different factors (e.g., biological, physiological, socio-economic, cultural) that can affect the paralanguage an individual employs. For instance, biological factors such as gender, age, and anatomical features heavily influence the physical ability to produce certain sounds or ranges of sounds. Pitch usually deepens as one enters into adolescence and into adulthood and then elevates again in senior years. Additionally, the anatomy of the male vocal tract typically produces deeper-pitched sounds than the anatomy of the female tract.

Many paralinguistic cues are affected by cultural or regional factors. Individuals who live in the southeast United States, for instance, employ a slowed speech tempo with lasting emphasis on certain syllables, resulting in what is sometimes referred to as a drawl. Residents of the US state of Indiana are known for their nasality. Dialects the world over include vocal as well as verbal features that distinguish them.

Voices also differ from individual to individual. A voice style consists of numerous paralinguistic elements or cues. Paralinguistic cues refer to elements such as pitch, tempo, loudness, voice quality, and others. Each person’s vocal cavity, tongue, and nasal cavities produce voice qualities that are so individual that law enforcement can use them to develop voiceprints that are analogous to fingerprints. Humans detect these differences as distinctive voice styles such as breathy, tense, raspy, or resonant. For example, celebrities and media personalities are quite often recognized by their distinctive voice qualities or styles.

Paralinguistic Cues

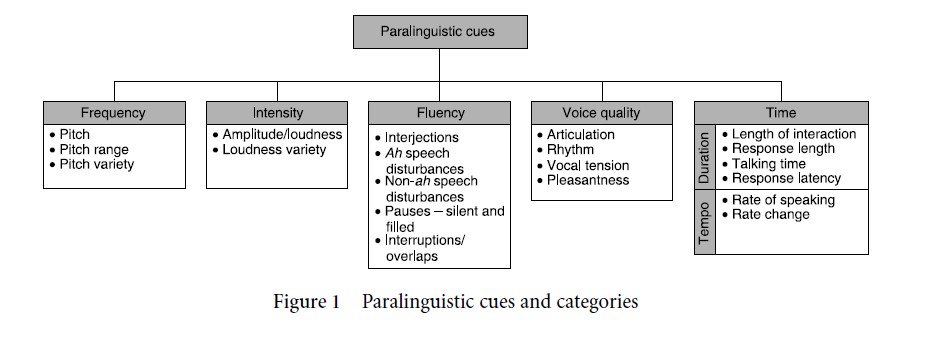

Paralinguistic cues can be roughly subdivided into five general categories – frequency, intensity, fluency, voice quality, and timing. Figure 1 shows several cues in each of these categories. A description of each category and its cues follows.

Frequency And Intensity

Any paralinguistic cue that deals with pitch is grouped under the frequency category. Of all paralinguistic cues, pitch (which is the perceptual label for fundamental frequency) is perhaps the most versatile in conveying different messages. In many languages, such as English, Spanish, and German, pitch, in conjunction with emphasis on specific words (e.g., “Well”), can convey a change in meaning (e.g., surprise, contempt, anger, disappointment) even though the word is the same. However, in certain other languages, such as Chinese, Thai, and Vietnamese, pitch inflections may actually convey a different word (Poyatos 2002). Changing pitch at junctures such as the end of sentence boundaries can also change meaning. In English, when a question is posed, even if not in correct grammatical structure, the voice pitch is typically elevated at the end of a sentence.

Figure 1 Paralinguistic cues and categories

Pitch and its variability have been linked to physiological changes due to arousal and certain types of emotion. Researchers suggest that low pitch levels (in association with other paralinguistic cues) may be associated with boredom, anger, and disappointment, whereas elevated pitch levels may be associated with happiness, surprise, and anger again (Davitz & Davitz 1964; Scherer & Ekman 1982). Some emotions (e.g., anger) may either increase or decrease pitch level, requiring an observer to rely on other cues to infer the emotion. In general, pitch levels rise when an individual is trying to communicate praise or sincerity, or to appear less rigid.

Vocal cues dealing with the loudness of the voice are grouped under the intensity category. Emotions such as joy and anger may be conveyed using increased volume, whereas sadness and empathy are often conveyed using decreased volume. Research also suggests that loudness may reveal a speaker’s sincerity or confidence (Rockwell et al. 1997). Certain emotions typically employ a greater variation in loudness than others. For example, someone who is angry often exhibits larger variation in volume than someone who is calm. Additionally, the intensity of voice may be used strategically to assert power or dominance in an interaction.

Fluency

Any paralinguistic cue that deals with the general flow of the speech belongs to the fluency category. This category can be further divided into interjections, checkbacks, interruptions, and silent pauses.

Interjections, also known as vocal segregates, include words that interrupt the smooth flow of speech. Ah speech disturbances are a common type of interjection. Examples of ah speech disturbances include words such as um and ah. Interjections are common in speech, but are typically omitted in written text. Non-ah speech disturbances include other filler words that are not in the ah speech disturbances sub-category. Examples include like, I mean, and whatever. Also included are other forms of dysfluency such as repetitions, stutters, garbled sounds, hesitancies, and halting speech.

Another interruption to the smooth flow of speech occurs when an individual interjects a question that requires a response from the conversational partner. These questions are often used to assess whether or not there is shared understanding of what is being communicated, but they also can be used by the person speaking to allow for more time to gather his or her thoughts. These questions are known as checkbacks. Examples of checkbacks include questions such as Know what I mean? Ya know? Right? OK? and Got it? (Buchholz 2000). Another type of interruption is overlap in speech of the subject and the interviewer. Often such overlap results in a change of turns.

Not all speech disturbances are filled with audible sounds. Like other disturbances, silent pauses may allow individuals to assess understanding or prepare for upcoming speech. A certain amount of silence exists in most speech. A silent pause is considered a speech disturbance when the amount of silence in the pause exceeds the amount of silence expected. The tempo, rhythm, and silent pauses of earlier speech impact the amount of silence that is expected.

Voice Quality

Paralinguistic cues that deal with articulation, rhythm, and tenseness or pleasantness of the voice are grouped under the voice quality category. Articulation may be associated with conveying different emotions. Researchers have observed that emotions such as pleasure, happiness, and surprise exhibit more clipped articulation than boredom, disgust, or sadness (Rockwell et al. 1997). Other researchers suggest that clipped articulation is often used “for addressing someone in a harsh or impatient tone (‘Com’n, get out’f here!’); warning against impending danger (‘Watch out!’); remembering suddenly (‘Wait!’)” (Poyatos 2002).

Rhythm of speech involves the combination of pitch, loudness, syllabic duration, and overall tempo (Poyatos 2002). Other paralinguistic cues, such as nonfluencies and response latency, also impact the perception of the rhythm of a conversation. Rhythm can be viewed on a scale from staccato-like, clipped articulation at one end to smooth, drawn-out speech at the other. Vocal tension or stress in the voice can be caused by a physiological change due to arousal. When a person is under stress, micro-muscle tremors in the vocal tract are transmitted through speech. These micro-muscle tremors are generated by the vocal cords that vibrate in the 8 –12 Hz range.

Other attributes of voice quality related to vocal pleasantness – such as resonance, breathiness, and nasality – may also change when an individual experiences different emotions. Researchers have found that individuals often deem utterances false when there is a switch in the speaker’s voice quality. For more detailed descriptions of voice styles and qualities – such as breathy, laryngealized, nasal, falsetto, harsh, squeaking, screeching, squealing, squawking, hollow, whining, whimpering, twangy, and moaning – see Poyatos (2002).

Timing

Paralinguistic cues related to the duration or the speed of an utterance are grouped under the timing category. The duration sub-category includes cues for overall length of an interaction, response length, total amount of talk time, and response latency. Length of interaction refers to the total duration of an interaction between conversational partners. Response length refers to the total length of an individual’s response to a question. Speaking duration refers to the proportion of the total time of the interaction that the subject spends talking or interacting. Response latency refers to the amount of time between when a question ends and when the subject begins a response. A response latency that is too long or too short interrupts the overall flow of the conversation. Many people attribute prolonged response latency to increased cognitive effort and a short response latency to anticipation, impatience, or wanting to get the next word in.

The tempo sub-category includes cues that gauge the rate of an individual’s speaking and the change in that rate. Rate of speaking refers to the “relative speed or slowness in the sequential delivery of words, sentences and the whole of a person’s speech” (Poyatos 2002, 8). Nonfluencies such as interjections and filled pauses affect the tempo of a person’s speech. Tempo has been formally calculated by researchers by taking the number of words or syllables spoken divided by the total time of a response or by the proportion of voiced segments to total voiced and silence segments. Tempo is a major component of an individual’s basic voice style, but it can be influenced by a number of factors. Certain grammatical elements, such as a parenthetical comment, are often conveyed with a change in tempo. Additionally, when someone misspeaks, stutters, or introduces errant information, often the subsequent repairing sentence is said with increased tempo. Tempo may also be tied to certain emotions or states of arousal. For instance, someone who is angry may have very slow, deliberate, tense speech. Someone who is confident may speak at a faster tempo. Researchers have studied tempo in a variety of contexts, including differences in the rate of speaking throughout a conversation or interview.

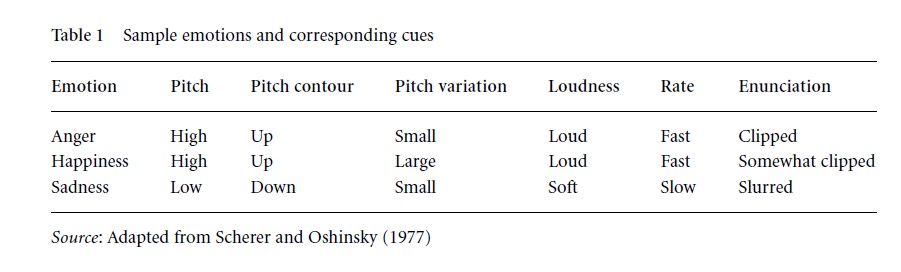

Table 1 Sample emotions and corresponding cues

Paralanguage To Convey Emotions And Personality Traits

An individual can convey emotions through a variety of paralinguistic cues. For example, one may convey sincerity about an opinion by using a softer but firm voice. Table 1 provides sample emotions and a few of their corresponding cues. For a more comprehensive analysis of the association between paralanguage characteristics and different emotions see Scherer (2003).

Paralinguistic cues can also be used to infer personality traits. For instance, people who are animated or extraverted often have a faster rate of speaking than those who aren’t. Conversely, people who are withdrawn tend to have a “flatter” tone of voice. While paralinguistic cues such as these can be broadly associated with personality traits, it would be incorrect to conclude that these associations are consistent all of the time.

Paralanguage is an integral part of our communication toolset that allows us to convey emotion, modify meaning, or communicate an attitude. Most paralanguage occurs in a face-to-face environment. However, with the development and increased use of technology in recent years, conveying paralanguage through other communication media is becoming more popular. For instance, individuals using text-only communication channels might use font size, coloring, capitalization, or non-alphabetic characters as a proxy for traditional paralinguistic cues. Instant messaging programs have implemented emoticons that can substitute for paralinguistic cues not available in text-based communication media. Even with the increased availability and understanding of substitutes, however, the use of paralanguage in text is relatively limited.

References:

- Buchholz, W. (2000). Nonfluencies & fluencies. At http://atc.bentley.edu/faculty/wb/presentations/paralanguage/outlinee.htm, accessed September 1, 2006.

- Davitz, J. R., & Davitz, L. J. (1964). The communication of feelings by content-free speech. Journal of Communication, 9, 6 –13.

- Hall, E. T., & Trager, G. L. (1953). The analysis of culture. Washington, DC: American Council of Learned Societies.

- Pittenger, R. E., Hockett, C., & Danehy, J. (1960). The first five minutes. Ithaca, NY: Paul Martineau.

- Poyatos, F. (2002). Nonverbal communication across disciplines. Vol. 2: Paralanguage, kinesics, silence, personal and environmental interaction. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Rockwell, P., Buller, D. B., & Burgoon, J. K. (1997). The voice of deceit: Refining and expanding vocal cues to deception. Communication Research Reports, 14(4), 451– 459.

- Scherer, K. R. (2003). Vocal communication of emotion: A review of research paradigms. Speech Communication, 40(1–2), 227– 256.

- Scherer, K. R., & Ekman, P. (1982). Methodological issues in studying nonverbal behavior. In K. R. Scherer & P. Ekman (eds.), Handbook of methods in nonverbal behavior research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press/Paris: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, pp. 1– 44.

- Scherer, K. R., & Oshinsky, J. S. (1977). Cue utilization in emotion attribution from auditory stimuli. Motivation and Emotion, 1(4), 331– 346.

- Trager, G. L. (1958). Paralanguage: A first approximation. Studies in Linguistics, 13, 1–12.