Specific communication disabilities affect the ability to understand and produce language. The most common hearing disabilities are congenital deafness and age-related hearing impairments. The primary causes for difficulties with the production of spoken language are traumatic brain injury, stroke, and dementia (Alzheimer’s and related diseases). Of additional relevance is the impact of visual impairment on reading and writing and on following nonverbal cues in conversation. Disability of any type creates psychosocial issues associated with personal and social adjustment, identity, and interactions with others.

This article focuses on the intergroup aspects of disability and communication. It acknowledges the importance of congenital disabilities, but emphasizes the challenges faced by the many individuals with acquired disability, where adjustment to major changes is required for the individuals and their social partners.

Stigma And Communication Predicaments Of Disability

As with many other social groups, societies create disability by categorizing human variation and building the boundaries through interpersonal, organizational, and societal activities (Higgins 1992). Negative stereotypes associated with disability include traits such as dependent, sick, unattractive, incompetent, burdensome, hypersensitive, and bitter. The stigma of disability is sustained by unquestioned societal values such as independence, beauty, and marketability (Hebl & Kleck 2000; Susman 1994).

Goffman (1963) highlighted the different issues faced in everyday interactions by persons with visible versus invisible disabilities. Those with visible disabilities (“discredited”) must deal with the anxiety resulting from their disability being public knowledge, while those with invisible disabilities (“discreditable”) contend with the burden of concealing information and of managing disclosure of their disability.

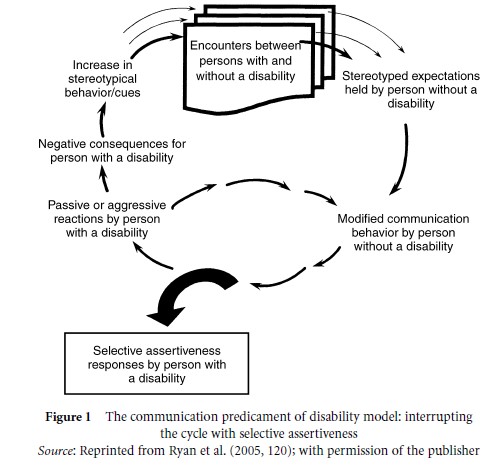

Based on communication accommodative theory, the communication predicament of disability model (Fig. 1) summarizes the negative feedback loop within which persons with acquired disabilities often find themselves (Braithwaite & Thompson 2000; Emry & Wiseman 1987; Ryan et al. 2005). Negative stereotypes lead able-bodied conversational partners to modify their behavior in ways that stifle real communication and reinforce expected behaviors from the person with disability. As with other intergroup situations, the expectation of homogeneity among individuals with disability is pervasive and particularly harmful. Persistent experiences of this nature (from family and friends as well as strangers) can lead to social withdrawal, lessened personal control, conformity to disability stereotypes, and to a reduced sense of self. Eventually, the person’s disabled identity contributes to more and more disabling communication situations in their interability interactions.

Figure 1 The communication predicament of disability model: interrupting the cycle with selective assertiveness

Modifications in communication toward persons with disability include changes in manner, language, and nonverbal behavior. The patronizing, paternalistic manner may be depersonalizing, impatient (or excessively patient), overhelping without consultation, or non-listening and dismissive. Talk can include simplified grammar and vocabulary, superficial topics, invasion of privacy, and high-pitched, exaggerated tone of voice. Gestures and facial expressions can support paternalistic language or undermine appropriate language choices. Being talked about or ignored in a three-person conversation is frequently experienced.

Reframing Disability And Consequent Reduction In Communication Barriers

Models of disability have traditionally been medicalor rehabilitation-oriented, while newer social models reframe the notion of disability. In particular, disability is now thought of as created largely through barriers in the environment rather than in the person, and living with a disability need not emphasize the traditional rehabilitation value of “normal.” Ableism is a term used by persons with disabilities themselves to emphasize the value of individual differences and to create the broadest context within which to thrive individually and as subgroups (Rauscher & McClintock 1997).

Selective assertiveness is featured in the model in Figure 1 as a conversational strategy for interrupting the automatic negative cycle created by stereotype-driven communication. Assertiveness is characterized by calm, confident, tactful, straightforward expressions of feelings and desires. As with stereotype-based communication, an assertive style is as much tone of voice and other nonverbal features as it is the direct, non-aggressive language used. Successful impression management strategies used by persons with disability include establishing normalcy by emphasizing similarities, using modeling behavior, limiting attention to assistive devices, limiting responses to overly personal questions, and managing the able-bodied tendency to overhelp. When empowered with a sense of equality as a human being, the person with a disability can more effectively manage the communication predicaments which are a part of everyday life. Since assertiveness takes energy and has its societal costs, persons with disability choose their battles – when to go along, when to get what one needs at the moment, and when to educate or advocate more generally (Fox & Giles 1997).

Intergroup communication strategies have also been used selectively by persons and groups with disability to meet the social identity goals of social creativity and social competition. The disability community has contributed actively towards redefining models of disability, such as ableism and the independent living model (Rauscher & McClintock 1997). This latter emphasizes the competence of persons with disability to make their own decisions regarding care and emphasizes equal social access to needed resources. The disability community is also active in the shaping of terminology for reference to persons with disability of various types and in developing ingroup language to enhance solidarity. With regard to social competition, disability groups have succeeded in North America in establishing disability acts to eliminate barriers in buildings, streets, transportation, and law.

Communication Technology And Images In The Media

Communication devices need to be learned and have their own influence on conversational interactions (e.g., blowing or eye movement technology to run a synthesized voice). A key issue for the future concerns how the rapidly burgeoning improvements in assistive technologies will affect interability communication (Braithwaite & Thompson 2000).

Computer-mediated communication offers persons with visible disabilities the opportunity to connect with others on an equal footing since their disability disappears in this medium. In addition, many individuals and disability organizations take advantage of computermediated self-help/mutual aid groups to build ingroup solidarity, plan advocacy, and support each other in their interability interactions.

With regard to media images of disability, autobiographical writings by persons with disability have a powerful impact in individualizing the disability experience. Writers with many types of disability (e.g., visual and hearing impairments, physical paralysis or weakness, vertigo, cognitive impairment, mental illness, spinal cord injury, chronic disabling illnesses) are expressing their emerging identities by selecting to be assertive through publishing books or articles aimed at others with their specific disability as well as education and advocacy directed toward caring professionals, policymakers, family members, and the general public (Ryan 2006). Similarly, images of persons with disability incorporated recently into major films and documentaries can counteract the societal lack of understanding about specific disabilities and about how well individuals can adapt to major functional restrictions. Disability advocates argue strongly for involvement of persons with disability in producing these media images – with the slogan “Nothing about us without us”.

Persons with acquired disability can use oral or written communication to reclaim their voices and to reshape their identities. As in all social interactions, the process of expressing their emerging identities contributes reciprocally to the reshaping of identity and changes in societal images of disability.

References:

- Braithwaite, D., & Thompson, T. (eds.) (2000). The handbook of communication and physical disability. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Emry, R., & Wiseman, R. L. (1987). An intercultural understanding of ablebodied and disabled persons’ communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 11, 7 –27.

- Fox, S. A., & Giles, H. (1997). Let the wheelchair through: An intergroup approach to interability communication. In W. P. Robinson (ed.), Social groups and identity: The developing legacy of Henri Tajfel. Oxford: Heinemann, pp. 215 –248.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hebl, M. R., & Kleck, R. E. (2000). The social consequences of physical disability. In T. F. Heatherton, R. E. Kleck, M. R. Hebl, & J. G. Hull (eds.), The social psychology of stigma. New York: Guilford, pp. 419 – 439.

- Higgins, P. (1992). Making disability: Exploring the social transformation of human variation. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

- Rauscher, L., & McClintock, M. (1997). Ableism curriculum design. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffen (eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice: A sourcebook. New York: Routledge, pp. 198 – 227.

- Ryan, E. B. (2006). Finding a new voice: Writing through health adversity. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26, 423 – 436.

- Ryan, E. B., Bajorek, S., Beaman, A., & Anas, A. P. (2005). “I just want you to know that ‘them’ is me”: Intergroup perspectives on communication and disability. In J. Harwood & H. Giles (eds.), Intergroup communication: Multiple perspectives. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 117–137.

- Susman, J. (1994). Disability, stigma and deviance. Social Sciences and Medicine, 38, 15 – 22.