A common finding in media research is that age groups differ in the amount and functions of their media use. Communication scholars have pointed out two possible explanations for such differences. First, there are life-cycle or maturational explanations: media use is supposed to change across the life-span in response to an individual’s development. Second, there are generational explanations: people who are born in a certain period are supposed to adopt particular patterns of media use. For example, research shows that older people spend more time watching television than do younger age groups. It may be that older people watch more television than when they were younger because their situation and needs have changed. Alternatively, older people may watch more television than younger people because television is more important to their generation than it is to younger generations.

Theoretical considerations have focused on age. Empirical research shows relations between media use and age. However, researchers writing on life-cycle explanations have argued that this “chronological age” has its limitations as a concept, because it is not the factor that explains the changes in media use across the life-span. In the example: older people watch more television than when they were younger not because their age has changed but because their situation and needs have changed. Therefore, researchers came up with alternative concepts, such as life-span position and contextual age, that are more insightful regarding developments across the life-span. In generational explanations, the concept of “formative years” is important. Generations are supposed to acquire a strong attachment to the media that they use during these socializing years. For example, the generation growing up in the 1990s (sometimes referred to as generation y or the net generation) witnessed the introduction and popularization of information technologies such as the Internet, email, and mobile phones in their younger years; this may lead to a continuing strong affection for these media during later stages of their lives.

There are methodological problems in trying to disentangle these life-cycle and generational influences on media use. Fortunately, cohort analyses have been conducted that provide some insight into these coexisting influences (“cohort” is the methodological term for people who are born in a certain period). These theoretical and methodological issues regarding media use across the life-span will be discussed below. Information on research that focuses in more depth on media use at a particular stage of life can be found in other articles.

Theoretical Concepts

The basic notion in life-cycle explanations is that media use is related to biological, cognitive, and social development across the life-span. The general idea is that when people pass through the stages of life they experience changes and therefore their media use changes as well. Several authors (e.g., Dimmick et al. 1979; Rosengren & Windahl 1989) have described this process using the uses and gratifications paradigm. Central to these descriptions is that developmental events and processes create needs as well as resources (such as physical or material resources). Subsequently these needs and resources bring about certain types of media use. For instance, several developments can take place in old age: many older people retire and experience physical aging, and some are confronted with losses in their social networks. These developments may lead to new needs, such as the need for activities to pass the newly available time or the need for company. Changes in resources are also apparent. These changing needs and resources may lead to new patterns of television use, for example spending more time viewing or using television more for company than before (van der Goot et al. 2006).

This developmental perspective implies that it is not chronological age that explains changes in media use. The term “life-span position” (Dimmick et al. 1979) has been used to indicate that it is more insightful to think about the relation of media use to life stages such as childhood than to study the relation of media use and age. This raises the question of how to measure people’s position in the life-span. Rubin and Rubin argued (e.g., A. M. Rubin & Rubin 1986) that it would be better not to use age, but to assess indicators of life position directly. Therefore they developed the concept of contextual age. This construct includes six dimensions relevant to defining aspects of people’s situation: physical health, interpersonal interaction, mobility, life satisfaction, social activity, and economic security. A young person and an older person have the same contextual age if they score the same on these variables. However, chronological age is still commonly included in audience research. It is considered to be a marker variable, an indicator of the stages of life.

The main assumption in generational explanations is that the circumstances under which a generation grows up determine to a large extent this generation’s behavior later in life. Scholars argue that experiences during socialization or during adolescence, the so-called formative years, leave long-lasting impressions on values and attitudes, and continue to influence behavior at later stages of life (Peiser 1999). Generations are supposed to be different from each other because they have grown up in different societal, political, and economic circumstances. Similarly, scholars have argued that generations are different with regard to media use. Generations may adopt specific patterns of media use when they are young and remain faithful to those throughout the life-span (Mares & Woodard 2006). In other words, generations that are young when a particular medium becomes popular may have a stronger attachment to that medium than do previous or later generations.

Several generations have been identified in the twentieth century, with regard to America and to a lesser extent other western countries. The names and birth years are debated, but this identification approximately concerns the following: the pre-war generations (born before World War II); the baby-boomers (born between 1946 and 1964); generation X (born between 1965 and 1976); and generation Y (born between 1977 and 2001). Moreover, generations have been defined in terms of the media they grew up with. So far, a television generation and a net generation have been distinguished. The television generation consists of those people that were young during the introduction and spread of television. A definition in terms of years of birth should be country-specific depending on the diffusion of television. In the United States those born in 1950 or later are supposed to be the television generation; in a study in Germany the television generation was operationalized as the people who were born after 1965 (Peiser 1999). The television generation is supposed to have a stronger affection for television and to be less inclined to read than previous generations. The term “net generation” is used for the generation growing up with information technology, most importantly the Internet. This generation has been defined as the people born between 1977 and 1997 (Tapscott 1998). So in America the television generation partly coincides with the baby-boom generation, whereas “generation Y” and “net generation” are different names for roughly the same generation.

Empirical Research

Ideally, research would provide a picture of the changes in media use across the life-span and the ways in which this media use is influenced by people’s formative years. To gain insight into these life-span and generational influences on media use, it is necessary to have information about the media use of several generations from their childhood to old age. However, this involves methodological problems that will be discussed below. Subsequently, research will be discussed that sheds some light on media use across the life-span. Cohort analyses have been conducted with regard to time spent on television watching, and motives for viewing have been studied in relation to age. Content preferences across the life-span are discussed in other articles. Research on Internet use will be discussed briefly below, because so far this research leans toward generational explanations.

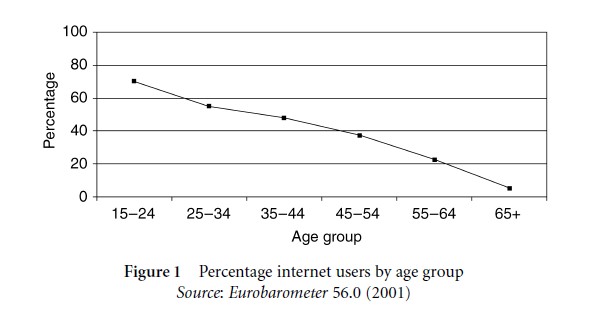

Most empirical research is cross-sectional, which means that it consists of data collected at one point in time. Cross-sectional research shows differences between age groups, but the problem is that older age groups represent both people in old age and older cohorts. This problem can be illustrated with the cross-sectional finding that younger age groups use the Internet more than do older age groups (see Fig. 1). The group aged 15 to 24 years refers to people in their late adolescence and early adulthood, but in Figure 1 it also refers to the group of people born between 1977 and 1986. This means that it is not possible to determine whether this age group uses the Internet more because they are at this stage of life, or because they were born in those years. In methodological terms: it is impossible to determine whether the differences are caused by life-cycle (age) effects or cohort effects.

In cross-sectional research, scholars can only try to come up with theoretical arguments for life-cycle or cohort effects. Are there reasons to assume that this age group of 15 to 24 years uses the Internet more because it fits better with the needs and situations of adolescents than with the needs of people at later stages of life? Such life-span explanations would mean that part of this group would stop using the Internet later in their lives, because later in life it would be less suitable to their needs. Alternatively, it could be argued that this age group of 15 to 24 years uses the Internet more than do older groups because they are part of the generation that has grown up with the Internet, whereas the older groups are part of generations that did not grow up with this technology. This generational explanation would mean that a large share of this age group would continue to use the Internet when they grow older.

Because cross-sectional research cannot disentangle life-cycle and cohort effects, other methods, such as cohort analysis, have been designed. To conduct a cohort analysis, data have to be available for several cohorts at a variety of life stages. It is necessary to have cross-sectional surveys with comparable variables on media use, and that have been carried out at different times of measurement. These data are hard to find, and therefore only a few cohort analyses on media use have been conducted (e.g. Danowski & Ruchinskas 1983; Peiser 1999; Mares & Woodard 2006). Moreover, scholars will have to wait many more years to be able to witness how media use develops across the life-span for the babyboomers and for generations X and Y. The baby-boomers will turn 65 from 2011 onward, and it will be interesting to see how their media use will change when they retire.

The cohort analysis by Mares and Woodard (2006) provides some insight into the development of the amount of television viewing across the life-span. The researchers used six measurement times (1978, 1982, 1986, 1990, 1994, and 1998) from the General Social Survey in which respondents were asked how many hours they watched television on an average day. Mares and Woodard found that throughout the life-span there are differences in viewing that are not explained by cohort effects. Even after controlling for cohort, period, sex, and education levels, there appeared to be an effect of age on the amount of viewing. Viewing was moderate among 15 to 28 year olds, declined throughout the late twenties, thirties, and forties, and gradually increased again in the fifties, and viewers aged over 60 watched more than younger age groups. Moreover, many cross-sectional surveys since the 1950s have found that older people watch more television than younger people. Therefore, scholars have emphasized life-cycle explanations in the case of time spent on television watching.

Mares and Woodard tested such life-cycle explanations for the finding that older people watch more television than younger people. It appeared that some older people watch more television than younger people because they do not have to go to work. To a lesser extent, some older adults watch more television than younger adults because of poorer health. Mares and Woodard stress that these descriptions apply only to some older people, because of the variability among older viewers. Older people turned out to be even more heterogeneous than younger age groups. Viewing levels were varied in early adulthood, became relatively stable in middle adulthood, and became more variable again as viewers got older.

Also, this cohort analysis yields some support for the concept of a television generation. Cohorts born just after the turn of the century (before 1905) watched the least television across the six measurement times. Later cohorts watched more, especially those born between the late 1940s through the 1960s. More recent cohorts showed something of a decline. This means that the cohorts that were in their childhood and teens during the introduction and popularization of television seem to have the strongest attachment to this medium.

The relation between motives for television viewing and age has been studied in some cross-sectional studies (e.g. Ostman & Jeffers 1983; Gunter 1998; Mundorf & Brownell 1990). Ostman and Jeffers formulated hypotheses on how motives for viewing would vary with the age of viewers. In this survey (N = 140, age 18 to 87), three motives for using television were positively related to age (to learn things; to overcome loneliness; to find something to talk about), whereas two motives were negatively related with age (to forget; to pass time when bored). Also, Rubin and Rubin (e.g., R. B. Rubin & Rubin 1982) conducted several surveys among adult and older samples in which they included their contextual age variables and variables on television viewing motives, program preferences, and viewing behaviors. These studies showed correlations between aspects of contextual age and aspects of television use. However, the research available so far does not present a clear picture of how motives for television viewing change across the life-span.

The Internet was introduced in the 1990s. From its introduction until now, many cross-sectional surveys have shown that older people have less access to the Internet and use it for a narrower array of activities than do younger people (e.g. Loges & Jung 2001). The concept of the digital divide has been used to indicate the gap between groups that are ahead in using new technologies and groups that lag behind. Within western societies, age is one of the factors associated with this gap. Most scholars lean toward generational explanations: the current generation of younger people will continue to use this technology when they grow older and therefore the age divide will probably disappear with time. On the other hand, other authors (Loges & Jung 2001) are cautious in ascribing the divide to a generational effect. They suggest that older people in 2040 may be similar to older people now. Therefore, differences between the Internet use of old and young people may survive.

References:

- Danowski, J. A., & Ruchinskas, J. E. (1983). Period, cohort, and aging effects: A study of television exposure in presidential-election campaigns, 1952 –1980. Communication Research, 10(1), 77– 96.

- Dimmick, J. W., McCain, T. A., & Bolton, W. T. (1979). Media use and the life-span: Notes on theory and method. American Behavioral Scientist, 23(1), 7– 31.

- Gunter, B. (1998). Understanding the older consumer: The grey market. London: Routledge.

- Loges, W. E., & Jung, J. Y. (2001). Exploring the digital divide: Internet connectedness and age. Communication Research, 28(4), 536 – 562.

- Mares, M. L., & Woodard, E. (2006). In search of the older audience: Adult age differences in television viewing. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 50(4), 595 – 614.

- Mundorf, N., & Brownell, W. (1990). Media preferences of older and younger adults. Gerontologist, 30(5), 685 – 691.

- Ostman, R. E., & Jeffers, D. W. (1983). Life stage and motives for television use. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 17(4), 315 – 322.

- Peiser, W. (1999). The television generation’s relation to the mass media in Germany: Accounting for the impact of private television. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 43(3), 364 – 385.

- Rosengren, K. E., & Windahl, S. (1989). Media matter: TV use in childhood and adolescence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Rubin, A. M. (1985). Media gratifications through the life cycle. In K. E. Rosengren, L. A. Wenner, & P. Palmgreen (eds.), Media gratifications research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, pp. 195 –208.

- Rubin, A. M., & Rubin, R. B. (1986). Contextual age as a life-position index. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 23(1), 27– 45.

- Rubin, R. B., & Rubin, A. M. (1982). Contextual age and television use: Reexamining a life-position indicator. In M. Burgoon (ed.), Communication yearbook 6. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, pp. 583 – 604.

- Tapscott, D. (1998). Growing up digital: The rise of the net generation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- van der Goot, M., Beentjes, J. W. J., & van Selm, M. (2006). Older adults’ television viewing from a life-span perspective: Past research and future challenges. In C. S. Beck (ed.), Communication yearbook 30. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 431– 469.

Back to Developmental Communication.