In the 1990s, accountability of advertising came high on the agenda in the commercial communication world. As a result a growing need for knowledge about the way the media environment influenced advertising effectiveness emerged. Standardized tools and new media studies were developed. And after 2000, greater actionability for media planners even on a day-to-day basis was incorporated into these measurement tools. Nowadays there is little argument in the commercial as well as academic world that campaigns should be monitored to better manage them in the marketplace.

Several factors were responsible for this development. On the advertisers’ side, financial control and return on investment (ROI) were stressed more in relation to advertising efforts than in the period before. The enormous growth of traditional and new media types and vehicles combined with an increase in commercial messages fighting for attention. This situation made involved parties curious as to which advertising messages are “getting over the hurdle.” As Franz (2000, 459) concluded: “This is the situation media research has to face in the near future: an unimaginable number of media for a more or less constant number of media users with limited time, money and (most important) attention capacities. The psychological key to coping with the overwhelming variety of media is selectivity.” And advertising effectiveness studies are necessary to conclude which messages can “fight” against this increasing selectivity and which messages get attention.

In this article three topics will be elaborated. Which research designs are adequate for measuring ad effect? Which key performance indicators, divided into advertising response and brand response, have to be selected? What future developments, like more insight into low attention processing, can we expect?

Research Design

Studying advertising effectiveness has an easy part and a difficult part (Bronner & Reuling 2002). Measuring advertising awareness and advertising response is the easy part. Any advertising study can measure awareness either continuously (“tracking design”), where different groups of respondents are contacted on a monthly, weekly, or daily basis, or pre/ post (before and after the campaign), where different groups of respondents are contacted at two different points in time. The difficult part is to answer the questions “What was the effect of the campaign upon brand response variables like brand awareness, brand sympathy, and brand usage?” and, if there is an increase in positive direction, “Is this increase due solely to the advertising campaign?”

Problems of the Pre/Post Model

Simple tracking and pre/post designs are not enough to answer these difficult questions, for two reasons: (1) an upturn in attitudes or brand ratings may have had nothing to do with the advertising; and (2) the chicken-or-the-egg problem arises if the “campaign aware” group has more positive attitudes or brand ratings than the “not-aware” group. The difficulty is to answer the question, “Was the increase in the number of positive ratings solely due to the advertising campaign?” Perceptions and behavior could have improved for a variety of reasons. The increase may have had nothing to do with the advertising.

Problems of the Exposed / Non-Exposed Model

Another possibility is to carry out only a post-measurement and divide it into two segments: exposed and non-exposed. Some researchers try to deduce effects by cross tabulating these two groups with effect variables. But it is clear that selective exposure can cause differences. If young people are more exposed and in advance have more positive attitudes, the correlation between exposed and positive attitudes is spurious. One also needs the “starting scores” of exposed and non-exposed citizens.

If, say, the post-measurement shows that the “exposed” group uses more energy-saving devices than the “non-exposed” group, can advertising receive the credit for this change? Not necessarily! As is often observed, it may be that a positive attitude toward energy saving has increased advertising awareness. In other words, the exposed population may already have had better energy-saving attitudes before the campaign than the non-exposed.

In commercial advertising studies we see the same phenomenon: people with sympathy for brand X have a higher advertising awareness of that brand. So in a post-measurement the exposed have a higher brand X sympathy score than the non-exposed. It is obvious that we cannot ascribe this difference to the campaign. The exposed population already had sympathy for brand X long before the campaign started. This is what is sometimes called the “chicken-or-the-egg problem”: which came first – brand sympathy or ad awareness?

Combination of the Two Models as a Solution

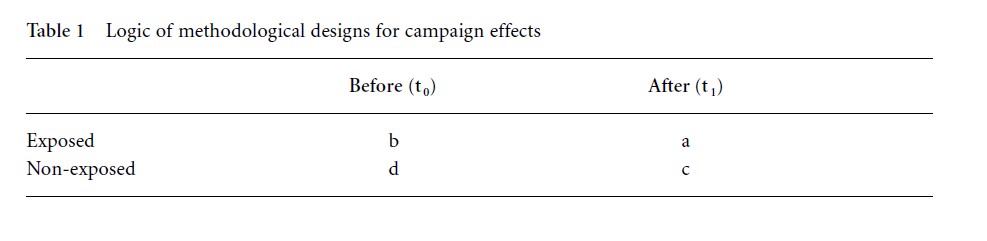

What is the solution? When we combine the two designs (pre/post and exposed/ non-exposed) we obtain a very powerful tool (Table 1). For each effect variable, the campaign effect score E = (a − b) − (c − d). The part (c − d) can be considered as an indicator about developments taking place in the world concerning this effect variable that are not due to the campaign. Thus the term (c − d) represents the changes that take place separately from the campaign. So we can separate campaign influence from other factors such as high levels of media attention.

The main question in the scheme above is how to establish in the pre-test whether someone is exposed to the campaign or not. The solution is the use of panels. Data are collected in two ways. In the combined panel/ad hoc design a pre-measurement is carried out in sample X. After the campaign this sample is subjected to a limited reinterview, only to establish if they were exposed to the campaign or not. These exposure scores are added to the pre-measurement. An independent post-measurement is carried out in sample Y in which both exposure and effect variables are measured.

In a panel design a pre-measurement is carried out and after the campaign a full reinterview with effect variables and exposure questions takes place. Many clients consider the first of these options as too expensive and statistically complicated. The second option, a panel with full reinterviewing, is easy to grasp and delivers adequate data for the scheme.

Key Performance Indicators

Strategic communication management is a method in which communication is continuously measured and analyzed and the media strategy is adapted to improve its effectiveness and efficiency. Den Boon et al. (2005, 64) make the following comparison to explain the core elements of strategic communication management: “it works like driving a car: concentrate on where you want to go, where the other cars are and how the vehicle is performing. Use a dashboard with a navigator to help get where you want to go.” These authors also describe the five central elements of strategic communication management, all centered on key performance indicators: (1) definition of key performance indicators by the advertiser in relation to brand and target group; (2) monitoring of own key performance indicators and those of the competition; (3) analyzing performance of the media and their synergy in terms of effectiveness and efficiency in achieving these key performance indicator targets; (4) analyzing media strategy in terms of optimal contact frequency of different media and optimal timing; and (5) adapting media and creative strategy.

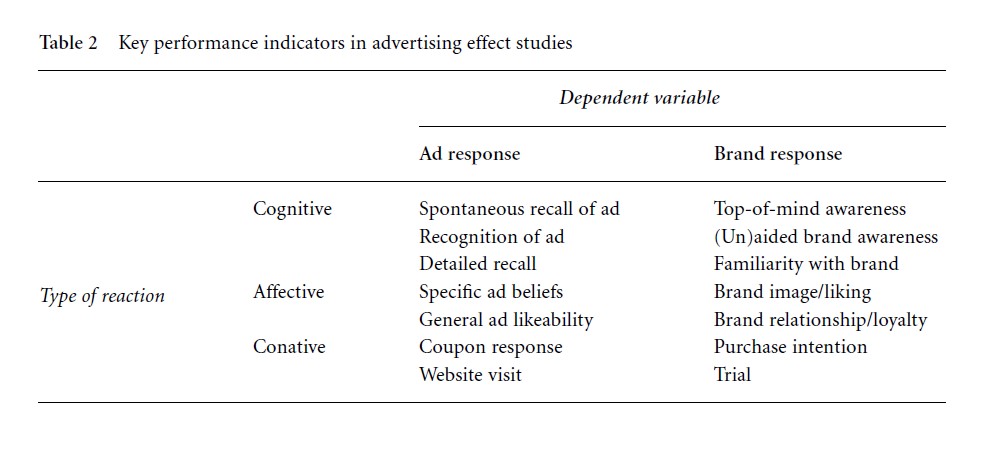

Of course the measured indicators vary according to campaign and measurement model, but a general line can be detected and Table 2 sketches the most used metrics.

Ad Response

Daniel Starch wrote as long ago as 1923 that for an advertisement to be successful it must be (1) seen, (2) read, (3) believed, (4) remembered, and (5) acted upon. In the Starch philosophy, as today, an advertisement must first be seen. So we start the detailed description of the cells of Table 2 with ad response–cognitive. How can we measure adequately if a consumer has seen an ad (cognitive response)? In the research world there are two schools of thought on this: (1) measure spontaneously (recall, e.g., “What brand of beer was advertised during TV program x?”), or (2) show the TV commercial or print ad and ask if the consumer has seen it (recognition). The discussion of which method is better has been going on for 40 years. Smit studied this problem in several experiments and concludes (1999, 110) that measuring noticing ads by means of recognition results in more correct claims. DuPlessis (1994) has an explanation for this result: visual prompts (as used in recognition) fit the memory traces better than verbal prompts (as used in recall). Advertising is largely visual, so it is logical to use visual methods to measure effects.

For affective ad response in a standardized approach, one set of beliefs about ads is used to be able to compare strong and weak points of the ads over all beliefs. But because campaigns and resulting ads have different communication goals, a better approach seems to be to adapt the measured beliefs to the goals.

For conative ad response behavioral measures can be used – as opposed to relying on consumer research to measure if the ad is seen and what consumers’ reactions are. In the classic situation coupon response was such a measure. Nowadays print ads and TV commercials include in many cases a lead to an Internet site or a free telephone number. Post hoc qualitative research among coupon senders or site visitors can indicate more about the advertisement’s role.

Brand Response

The effect of advertising upon brand awareness (cognitive brand response) is in nearly all effect studies measured in three steps: top of mind (“Which beer brands do you know?” – first one mentioned), spontaneous (“Which beer brands do you know?” – all brands mentioned), aided (“Here is a list of beer brands with their logos. Which ones do you know at least by name?”). Familiarity can also be measured and is a more nuanced scale.

For the measurement of affective brand response the brand that is the focus of the campaign and the main competitors are measured on a salient list of attributes (brand beliefs) relating to corporate-, product-, and user-profile facets. Smit et al. (2007) describe validated instruments that can be used, for example the multidimensional brand personality construct proposed by Aaker (1997), based on the famous “Big Five” in personality research.

Likely changes in behavior (conative brand response) are measured through the introduction of such measures as purchase consideration and intention. Purchase intention measures on a kind of probability scale are a generally accepted measure for the conative part of brand response. For new products a trial measure is more common (“As you may have heard brand x is bringing out . . . How likely is it that you would try them in the first few months after they become available in the shops?”). Another measurement tool is using a constant sum procedure (“Please divide 100 points over the brands in your evoked set in relation to buying probability”). The advantage of this procedure is that we get a better understanding of the relative position of a brand.

Future Developments

At least three developments will influence advertising effectiveness measurement: low attention processing, simultaneous media usage, and multimedia synergy effects.

As already stated, recognition is a more powerful memory system than recall, but as Heath (2004) states, advertising can influence future buying decisions even when subjects do not recollect ever having seen the ad. His low-attention-processing (LAP) model uses passive and implicit learning to create and reinforce links between elements in advertising and emotional “markers” in semantic memory. It predicts that advertising can work being seen several times, and that brand associations reinforced by this repetition may remain in memory long after the ad itself has been forgotten (Heath 2004, 37). Neuro-marketing may shed more light on this phenomenon in the next years.

Increasing simultaneous media exposure also raises questions on how media advertising should be planned and measured in the near future (Schultz et al. 2005). Consumers use increasingly multiple forms of media, all at the same time; younger people especially sometimes use three or more media at the same time (e.g., Internet, radio, TV). They are exposed to messages simultaneously. What about conflicting message exposures occurring simultaneously?

Finally, the use of multimedia and cross-media strategies will influence the measurement of advertising effectiveness. Successful campaigns more and more use several media types to effectively communicate their message (Bronner & Neijens 2006). Interaction of different media in one campaign can have a number of synergy effects (Bronner 2006). Multimedia campaigns show higher brand effects (Chang & Thorson 2004). In the effect research in the future there will be a strong need not only to detect the effects of a campaign but also to be able to ascribe these effects to certain media or combinations of media.

References:

- Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 3, 347–356.

- Boon, A. K. den, Bruin, S. M. A., & van de Kamp, T. J. F. (2005). Measuring and optimising the effectiveness of mixed media campaigns. Proceedings of the Fourth Worldwide Audience Measurement Conference (WAM), Montreal, June, 61– 90.

- Bronner, A. E. (2006). Multimediasynergie in reclamecampagnes [Multimedia synergy in advertising campaigns]. Amsterdam: SWOCC.

- Bronner, A. E., & Neijens, P. (2006). Audience experiences of media context and embedded advertising: A comparison of eight media. International Journal of Market Research, 48(1), 81–100.

- Bronner, A. E., & Reuling, A. (2002). Improving campaign effectiveness: A research model to separate chaff from campaign wheat. In G. Bartels & W. Nelissen (eds.), Marketing for sustainability. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 150 –159.

- Chang, Y., & Thorson, E. (2004). Television and web advertising synergies. Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 75 – 84.

- DuPlessis, E. (1994). Recognition versus recall. Journal of Advertising Research, 34(3), 75 – 91.

- Faasse, J., & Hiddleston, N. (2002). Multimedia optimizing optimistics. Paper presented at ESOMAR Congress Print Audience Measurement, Cannes, June.

- Fournier, S. M. (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 343 –373.

- Franz, G. (2000). The future of multimedia research. Journal of the Market Research Society, 42(4), 459 – 472.

- Franzen, G. (1998). Brands and advertising: How advertising effectiveness influences brand equity. Henley-on-Thames: NTC.

- Hall, M. (1992). Using advertising frameworks: Different research models for different campaigns. Admap, March, 17–21.

- Heath, R. (2004). Ah yes, I remember it well. Admap, 39(5), 36 –38.

- Percy, L., Hansen, F., & Randrup, R. (2004). How to measure brand emotion. Admap, 39(1), 32 –34.

- Putte, B. van den (2002). An integrative framework for effective communication. In G. Bartels & W. Nelissen (eds.), Marketing for sustainability. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 83 – 95.

- Schlinger, M. J. (1979). A profile of responses to commercials. Journal of Advertising Research, 19(2), 37– 46.

- Schultz, D. E., Block, M. P., & Pilotta, J. J. (2005). Implementing a media consumption model. Proceedings of the Fourth Worldwide Audience Measurement Conference (WAM), Montreal, June, 71– 92.

- Smit, E. (1999). Mass media advertising: Information or wallpaper? Unpublished dissertation, University of Amsterdam.

- Smit, E. G., Bronner, F., & Tolboom, M. (2007). Brand relationship quality and its value for personal contact. Journal of Business Research, 60(6), 627– 633.

- Starch, D. (1923). Principles of advertising. Chicago: A. W. Shaw.