A caricature is an exaggerated and distorted image of a person or thing, which is characterized by visual likeness, immediate recognizability, and pictorial wit, irony, or satire. This visual burlesque can be insulting or complimentary. It is not uncommon that a caricature offends the sensibilities of a depicted person.

Caricatures can serve editorial, illustrative, entertainment, or commercial purposes, as part of political cartoons, illustrations for books and articles, standalone artwork, or use in publicity and advertisements. Caricatures can be standalone drawings or well-integrated depictions in a broader context. For example, caricatures of politicians can be one part of an editorial cartoon that comments on a political issue.

History Of Caricature In Europe

Etymologically the word “caricature” originates from the Italian verb caricare, which means “loaded” or “overloaded,” and the Italian noun carictura. The word caricare first appears in Italy around 1600, at the time of the rise of the artistic genre ritrattini carichi (exaggerated pictures). In a preface to the 1646 published collection of etchings of the drawings of Annibale Carracci (before November 3 1560 –1609), it was pointed out that Carracci had employed caricare for sketchy, satirical, and exaggerated portrait drawings. Carracci’s fundamental idea was that in nature there is nothing like perfect beauty or total ugliness. From his point of view, perfect objects could only be created artificially by artists. For absolute ugliness the existing features must be exaggerated. In the sense used by Carracci, caricatures are simply drawings where quirks or imperfections of nature are highlighted and accentuated rather than corrected or idealized.

The art of caricatura was further developed by Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598 –1680). Aside from the external appearance of a depicted person, it was important for him to expose internal characteristics of personality or temperament. The intention behind this approach was not only to exaggerate unusual or unattractive features but to make the depicted person seem ridiculous. During his occupation at the court of Louis XIV in 1665, Bernini introduced the term caricature to France. At the time, there was no conceptual equivalent for this term, which was translated into the French as portrait chargé. In the middle of the eighteenth century, the term caricature became popular in French.

In England the first definition of caricature appears in the Bibliotheca abscondita in 1686. Here, caricature was described as portraits of human faces using animal heads. In the middle of the eighteenth century there was a dispute over whether or not caricature satisfies artistic demands and quality criteria. William Hogarth (1697–1764) described caricature as “scrawniness.” In 1743 Hogarth published his famous print “3 Characters – 4 Caricaturas” to illustrate the difference between proper portraits and “scribbling.” This dispute seemed to fade with the publication in 1813 of J. P. Malcom’s An historical sketch of the art of caricaturing, a compilation of caricatures that defined the nature of the art. From this point caricature is a term used widely for all depictions of persons employing exaggeration or deformation. In the second half of the eighteenth century caricature became the generic term for political, curious, emblematic, and comic prints.

The evolution of the term caricature has followed a circuitous route. For Carracci, caricature was an exaggerated depiction of individual physiognomic characteristics. For Hogarth caricature was a flawed rendering of a grotesque illusion. For both, caricature was the selective depiction of isolated individual physiognomic guises and features, normally limited to the face and head. They were drawings that exaggerated the unique mental, physical, and other discernible characteristics or features of a person (Unverfehrt 1984).

Caricatures gained popularity among the upper class with broadsheets circulated for distraction and enjoyment among aristocratic circles in France and Italy. It was a kind of honor to be depicted. And it was considered a pleasant pastime to view the exaggerated drawings. In Britain this kind of amusement also became popular around the middle of the eighteenth century. The rise of caricature as a genre is closely connected to some noteworthy artists. English artists Thomas Rowlandson (1756/7–1827), James Gillray (1757–1815), and George Cruikshank (1792 –1878) played important roles. Rowlandson’s early portrait drawings were strongly influenced by John Hamilton Mortimer (1740 –1779). Around 1780 his watercolors became more socially conscious and humorous. After the publication of his etchings in 1784, Rowlandson turned increasingly to illustration and caricature. With Dr Syntax, a fictitious figure he invented at the beginning of the nineteenth century for the publisher Ackermann, he drew the first English “cartoon” character (Bryant & Heneage 1994, 185 –187).

Like Rowlandson, James Gillray was influenced in technique and style by Mortimer. From 1786 he devoted himself to caricature exclusively. Gillray is renowned for his depictions of William Pitt the Younger (1759 –1806), British prime minister from 1783 to 1806. Gillray’s most famous etching and best-known political print is “The Plumbpudding in danger,” which shows Pitt and Napoleon Bonaparte carving up a globe to divide the world between them (Bryant & Heneage 1994, 90 – 92). George Cruikshank was the son of the caricaturist, illustrator, and painter Isaac Cruikshank (1764 –1811), who taught him to draw and etch. Cruikshank published his first caricature in 1806. He was especially famous for ridiculing George IV. However, in 1821 he abandoned caricature for straight illustration (Bryant & Heneage 1994, 50 –51).

In France, painter, sculptor, and lithographer Honoré Daumier (1808 –1879), perhaps the greatest social satirist of the nineteenth century, produced over 4,000 lithographs designed to comment upon and satirize social and political conditions in France and Europe. Appreciated as cartoons by his contemporaries, these prints are now considered masterpieces by many. A good deal of Daumier’s work was published in the magazines La Caricature and Le Charivari between 1830 and 1835. In 1832 his caricature of King Louis Philippe (1773 –1850) as Gargantua led to six months imprisonment. After La Caricature was suppressed, his worked appeared in Le Charivari, where he used a realistic graphic style to satirize and ridicule the bourgeois society of his day. In the later years, after 1848, he painted watercolors on the subject of jurisprudence. His visual skits about the Courts of Justice are well known. In old age, he went blind and died impoverished.

Political Cartooning In The Us

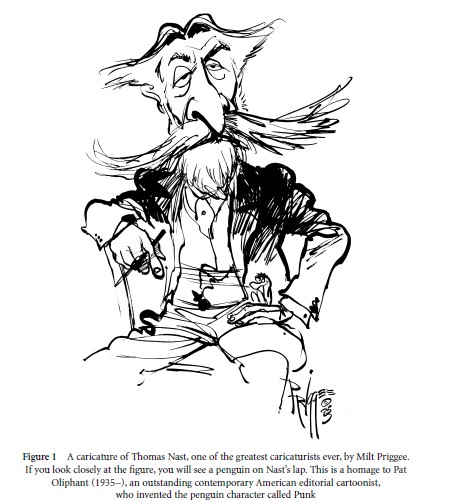

Figure 1 A caricature of Thomas Nast, one of the greatest caricaturists ever, by Milt Priggee. If you look closely at the figure, you will see a penguin on Nast’s lap. This is a homage to Pat Oliphant (1935 –), an outstanding contemporary American editorial cartoonist, who invented the penguin character called Punk

The German emigrant Thomas Nast (1840 –1902) carried the tradition of caricature and political commentary to the United States (see Figs 1 and 2). At the age of 15, Nast was discovered by the publisher Frank Leslie. Subsequently, his work appeared in the weekly magazine Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper. He joined Leslie’s struggle against the so-called “swill milk scandal” and experienced the power of the press for the first time. After three years Nast became a freelance for magazines such as Harper’s Weekly, the Sunday Courier, and the New York Illustrated News. As a sketch artist/correspondent for the New York Illustrated News, he accompanied Giuseppe Garibaldi’s troops in Sicily for four months in 1860, contributing sketches to newspapers in Britain, France, and the US. In 1861 he returned to the US, having improved his drawing technique. After the outbreak of the Civil War, Nast was employed as a sketch artist/reporter by Harper’s Weekly. In 1864 he supported Abraham Lincoln’s presidential campaign with his drawings. His cartoons attacking President Andrew Johnson in 1866 established his reputation as an exceptionally talented caricaturist and editorial cartoonist. During his artistic career Nast invented some of the familiar encodings still in use in the US today: for example, the Democratic Donkey, the Republican Elephant, and Santa Claus. He was also famous for his aggressive and sometimes offensive cartoon series about William Marcy “Boss” Tweed (1823 –1878) and the New York City political machine, as well as his anti-immigrant and racist depictions of Irish famine refugees. In the end Nast’s drawings were responsible for the cessation of the political career of Tweed.

Figure 2 Another Milt Priggee caricature of Thomas Nast

Modern Caricatures

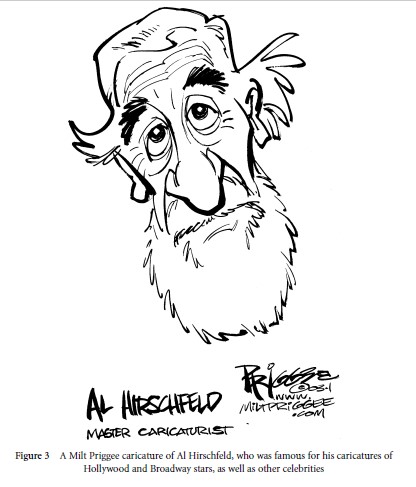

In the twentieth century the number of caricaturists working for newspapers and magazines, as well as creating books, comics, and animated cartoons, multiplied with the scale and reach of mass produced media. Milt Priggee (1953 –) was encouraged to become a caricaturist and editorial cartoonist by his mentor and Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist John Fischetti (1916 –1980). In his career Priggee has worked for the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun-Times, the Chicago Daily News, and the Spokesman-Review, among other media. Americans such as Al Hirschfeld (1903 –2003; see Fig. 3), David Levine (1926 –), Taylor Jones (1952 –), and Christopher Fox Payne, alias C. F. Payne (1954 –), as well as Austrian Erich Sokol (1933 –2003), the British Gerald Scarfe (1936 –), the French Jean Mulatier (1947–), the Italian Tullio Pericoli (1936 –), Swedes Ewert Karlsson, alias EWK (1918 –2004), and Riber Hansson (1939 –), and Germans Dieter Hanitzsch (1933 –) and Bernhard Prinz (1975 –) enjoyed long and distinguished careers and contributed to the establishment of caricature as a routine practice in western culture.

Figure 3 A Milt Priggee caricature of Al Hirschfeld, who was famous for his caricatures of Hollywood and Broadway stars, as well as other celebrities

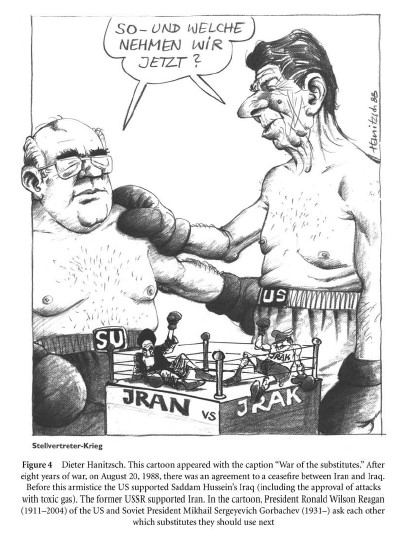

Some of them, such as EWK, Hanitzsch, Hansson, Priggee, and Sokol, are not only famous for their caricatures but for their editorial cartoons. Dieter Hanitzsch pioneered animated editorial cartooning. Hanitzsch began his career as head of advertising at the Paulaner Brewery. As an editor for the economics section at a public broadcast station, he regularly produced cartoons and caricatures. In 1985 Hanitzsch became a full-time cartoonist for the German quality paper Süddeutsche Zeitung and other print media (Fig. 4). Together with the renowned journalist Herbert Riehl-Heyse ( 1940-2003 ), Hanitzsch invented the virtual conservative Bavarian politician “Max G. Frosch hammer.” This cartoon character comments on weekly political events in Germany and Bavaria. First run as a weekly comic strip in the Suddeutsche Zeitung, this political satire is now broadcast as an animated cartoon by Bavarian television (~Television; Television as Popular Culture).

Figure 4 Dieter Hanitzsch. This cartoon appeared with the caption “War of the substitutes:’ After eight years of war, on August 20, 1988, there was an agreement to a ceasefire between Tran and Iraq. Before this armistice the US supported Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (including the approval of attacks with toxic gas). The former USSRsupported Iran. In the cartoon, President Ronald Wilson Reagan ( 1911-2004) of the US and Soviet President Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (1931-) ask each other which substitutes they should use next

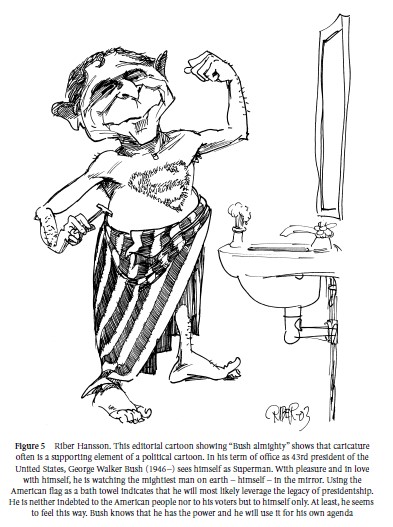

Figure 5 Riber Hansson. This editorial cartoon showing “Bush almighty” shows that caricature often is a supporting element of a political cartoon. In his term of office as 43rd president of the United States, George Walker Bush (1946 –) sees himself as Superman. With pleasure and in love with himself, he is watching the mightiest man on earth – himself – in the mirror. Using the American flag as a bath towel indicates that he will most likely leverage the legacy of presidentship. He is neither indebted to the American people nor to his voters but to himself only. At least, he seems to feel this way. Bush knows that he has the power and he will use it for his own agenda

Figure 5 Riber Hansson. This editorial cartoon showing “Bush almighty” shows that caricature often is a supporting element of a political cartoon. In his term of office as 43rd president of the United States, George Walker Bush (1946 –) sees himself as Superman. With pleasure and in love with himself, he is watching the mightiest man on earth – himself – in the mirror. Using the American flag as a bath towel indicates that he will most likely leverage the legacy of presidentship. He is neither indebted to the American people nor to his voters but to himself only. At least, he seems to feel this way. Bush knows that he has the power and he will use it for his own agenda

Drawings by Riber Hansson were published in Swedish papers like the Svenska Dagbladet and the Sydsvenskan. Furthermore, his cartoons were reprinted in Courier International, NRC Handelsblatt, and many other papers around the world. His work is represented in the National Museum of Art in Stockholm, the Swedish Library of Parliament, and many cartoon museums (Fig. 5).

By the twentieth century, caricature had come to be associated most often with political or editorial cartoons, visual frames, or opinion columns using unique tools like caricature, exaggeration, transformation, symbolism, narration, composition, design, and visual juxtaposition to construct ironic and satiric commentary. Editorial cartoons are filtered through the prism of the creator’s perspective, imagination, and artistic preferences. Therefore, any editorial cartoon will show an issue from a particular point of view, which may shift the balance of debate and provoke thoughts that range from anger to whims. Editorial cartoons not only have the right but also the liability to be painful, cynical, and provocative. In some respects, an editorial cartoon is nothing but a graphic sledgehammer.

However, caricature and cartoon are not the same. A caricature is an exaggerated depiction of a particular person, characteristic, or thing and so can be a component of any cartoon. As such, caricature is a potential but not essential part of any cartoon.

References:

- Bryant, M., & Heneage, S. (1994). Dictionary of British cartoonists and caricaturists 1730 –1980. Aldershot: Scolar Press.

- Gould, A. (ed.) (1981). Masters of caricature: From Hogarth and Gillray to Scarfe and Levine. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Knieper, T. (2001). Die Zukunft der politischen Karikatur. [The future of editorial cartooning]. In T. Knieper & M. G. Müller (eds.), Kommunikation visuell: Das Bild als Forschungsgegenstand – Grundlagen und Perspektiven. [The visual approach to communication: Researching the visual – Basics and prospects]. Cologne: Herbert von Halem, pp. 262 –278.

- Knieper, T. (2002). Die politische Karikatur: Eine journalistische Darstellungsform und deren Produzenten [The political cartoon: A journalistic format and its authors]. Cologne: Herbert von Halem. Koch, U. E., & Sagave, P.-P. (1984). Le Charivari: Die Geschichte einer Pariser Tageszeitung im Kampf

- um die Republik (1882 –1882) [Le Charivari: The history of a Parisian daily paper in the fight for the Republic (1832 –1882)]. Cologne: C. W. Leske.

- Lamb, C. (2004). Drawn to extremes: The use and abuse of editorial cartoons. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lent, J. A. (1994). Animation, caricature, and gag and political cartoons in the United States and Canada: An international bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Lucie-Smith, E. (1981). The art of caricature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Somers, P. P., Jr. (1998). Editorial cartooning and caricature: A reference guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Unverfehrt, G. (1984). Karikatur: Zur Geschichte eines Begriffs [Caricature: History of a term]. In G. Langemeyer, G. Unverfehrt, H. Guratzsch, & C. Stölzl (eds.), Bild als Waffe: Mittel und Motive der Karikatur in fünf Jahrhunderten [Picture as weapon: Instruments and motives of caricature during five centuries]. Munich: Prestel, pp. 345 –354.