The term “branding” is used for the identification of offers (products and services). Etymologically, the origin of the word can be found in the branding of cattle. Initially, the spectrum of meanings was closely restricted to the pure act of naming. In the course of time, a more tailored definition of branding was suggested: integrated and harmonized use of all marketing mix instruments with the aim of creating a concise, comprehensive, and positively discriminating brand image within the relevant competitive environment. However, this all-embracing concept is not clearly distinguishable from brand management. Hence, another definition situated between these two extremes has become widely accepted: the so-called magic triangle of branding. The triangle has the following three sides: brand name, trademark (for example, a logo), and product design and packaging. It is the task of branding to balance these three sides so that they position a brand uniquely (see also Aaker 1991; Aaker & Joachimsthaler 2000).

Brand Name

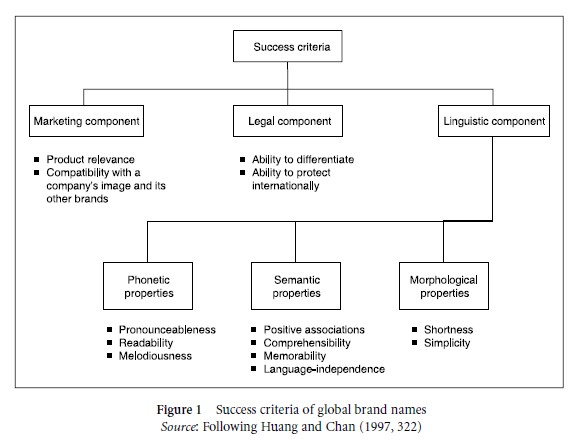

Faced with the increasing globalization of many markets, the issue of the creation of global brand names has recently received a lot of attention (Aaker & Joachimsthaler 1999). The criteria mentioned in this context (for example, short, simple brand names that release positive associations and are easily understandable and easily remembered) are of course also important for the branding of national brands. In a global context, however, such criteria as “short, simple, easily remembered” have to be more strictly observed or differentiated (cf. Fig. 1). This is valid, for instance, for a brand’s suitability to release positive associations. This is because associations frequently draw on symbolic meanings and symbols that are usually only understandable within one cultural realm. With regard to the phonetic properties (easily pronounceable and readable as well as melodious), global brand names also have to meet tougher demands. The so-called speech universals play a special role in this context. They are similarly effective in all alphabetical languages. One example is the universal sound symbolism of the vowels a and o (= large) and i (= small). Another one is the special effect that certain consonants have: brand names beginning with a plosive (= b, d, g, k, t) are significantly better recalled and recognized than other brand names.

Figure 1 Success criteria of global brand names Source: Following Huang and Chan (1997, 322)

Brand Logo

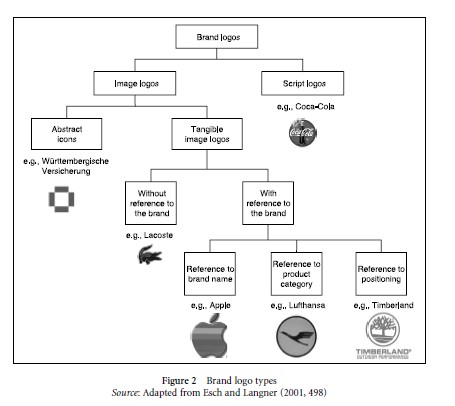

A decisive role is attributed to the brand logo (Buttle & Westoby 2006). This is due to the fact that, like all visual stimuli, it is processed more easily and quickly than the verbal stimulus of the brand name. Moreover, visual impulses are more memorable than verbal ones and take a direct path to stored associations in the brain. For this reason, image logos are used more often than script logos. The images may in turn be abstract icons or tangible pictures (cf. Fig. 2). From the relevant research on data processing, it is known that tangible graphic stimuli are better processed and remembered than abstract picture impulses. However, Esch and Langner (2001) found that, paradoxically, with regard to brand logos, people tend to convert the originally tangible (image) logos step by step into abstract (image) logos (e.g., the realistically represented Shell scallop into a stylized scallop).

Figure 2 Brand logo types Source: Adapted from Esch and Langner (2001, 498)

Independently of these fundamental problems, a great number of criteria have to be taken into consideration during the creation of brand logos (for example, the ease of identification, differentiation, and intelligibility, and the sympathy effect). Additionally, one has to decide which social techniques can guarantee that these criteria are fulfilled and in which design. Among those techniques are the use of cognitively surprising impulses that question established perception expectations, the use of emotional impulses (for example, through giving the logo childlike characteristics), and particularly the use of physically intense impulses. The organizational dimensions in this case are the structure (e.g., simplicity vs complexity), color (e.g., signal colors), and form. It can be proven, for example, that symmetrical forms are better perceived, used, and recalled and are furthermore more agreeable than asymmetric forms. But even within the category of symmetrical logos, essential differences have been found: Triangular forms tend to appear more lively, and round forms trigger associations in the direction of tenderness and softness. Square forms, on the other hand, may appear quiet and deliberate, when they are perceived as “passive” due to environmental factors, or hard and strong, when their context makes them appear “powerful.”

Product Design And Product Packaging

To the same extent as the brand name and logo, the design and packaging have to contribute to the high-quality, unique positioning of a brand (Bloch 1995). This can be obtained by a characteristic form and color as well as other features (for example, materials). However, the ability forms (i.e., regular, closed, and symmetrical ones), and by areas that do not contain too many colors and graphics. Brand names and brand logos should possess, however, a strong contrast between figure and background, i.e., the figure should stand out clearly from the respective background. Finally, Langner and Esch (2004) identified the factors of brand aesthetics that are important in this connection:

Harmony: Do the colors, shapes, and images used in product design and packaging evoke the same associations and match the brand positioning?

Modernity: Does the target group feel that product design and packaging are up to date?

Sophistication: Do product design as well as packaging signal elegance and exclusivity?

Emotionality: Do product design and packaging trigger positive feelings?

Complexity: Is the design overloaded and unclear on the one hand or too simple and boring on the other hand?

Intimacy: Do product design and packaging correspond to the brand knowledge and/or brand scheme of the target group?

References:

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. New York: Free Press.

- Aaker, D. A., & Joachimsthaler, E. (1999). The lure of global branding. Harvard Business Review, 77(6), 137–144.

- Aaker, D. A., & Joachimsthaler, E. (2000). Brand leadership. New York: Free Press.

- Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356.

- Bloch, P. H. (1995). Seeking the ideal form: Product design and consumer response. Journal of Marketing, 59(3), 16 –30.

- Buttle, H., & Westoby, N. (2006). Brand logo and name association: It’s all in the name. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(9), 1181–1194.

- Coomber, S. (2007). Branding. Chichester: Capstone.

- Esch, F-R. (2007). Strategie und Technik der Markenführung [Brand management: Strategies and techniques], 4th edn. Munich: Vahlen.

- Esch, F-R., & Langner, T. (2001). Gestaltung von Markenlogos [Design of brand logos]. In F-R. Esch (ed.), Moderne Markenführung [Modern brand management], 3rd edn. Wiesbaden: Gabler, pp. 495 –520.

- Henderson, P. W., & Cote, J. A. (1998). Guidelines for selecting or modifying logos. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 14 –30.

- Huang, Y. Y., & Chan, K. K. (1997). Chinese brand naming. International Journal of Advertising, 16(4), 320 –335.

- Langner, T., & Esch, F-R. (2004). Sozialtechnische Gestaltung der Ästhetik von Produktverpackungen [Social-technical design of the aesthetics of product packaging]. In A. Gröppel-Klein (ed.), Konsumentenverhaltensforschung im 21. Jahrhundert [Consumer behavior in the 21st century]. Wiesbaden: Gabler, pp. 413 – 440.

- Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and verbal processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Usunier, J-C., & Shaner, J. (2002). Using linguistics for creating better international brand names. Journal of Marketing Communications, 8(4), 211–228.