Earning public understanding and acceptance through reports in the press is one of the oldest means–ends schemes in public relations (PR). Firms, governments, NGOs, and interest groups alike use the media to convey their message to their publics. Hence, media influence is a two-step process. Whether PR efforts lead to news items in the media depends on the relations of the company with the media and on the newsworthiness of the publicity efforts. Once the media have published the news, PR media influence can be understood through theories about media effects.

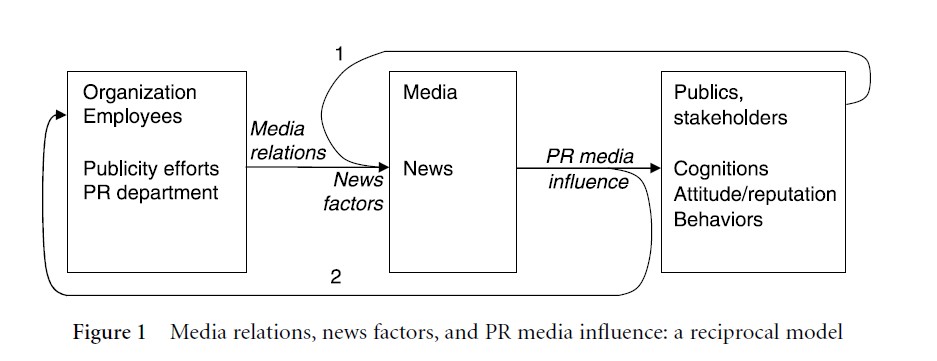

PR media influence is a special field of media effects because of the involvement of stakeholders. Every actor who may affect the company or may be affected by the company is a stakeholder. Typical stakeholders are competitors, investors, financial analysts, interest groups, employees, and consumers. Stakeholders are not simply external publics outside the organization, but active players in the publicity arena themselves, who also invest in media relations. Stakeholders may serve as alternative sources for journalists who want to verify their facts or to present both sides of the argument (Fig. 1, feedback loop 1). Stakeholders may also be located within the organization itself (feedback loop 2). Employees often learn from the press about takeover negotiations, organizational scandals, or the relative performance of their firm as compared to competitors, especially in global firms.

Figure 1 Media relations, news factors, and PR media influence: a reciprocal model

From a more abstract point of view, media and journalists, as well as an organization’s publics and stakeholders, can be conceived of as actors in an interorganizational communication network. A network perspective results in a reciprocal model of PR media effects.

Influence Of The Amount And Tone Of The News

Although it is a basic assumption throughout the PR community that stakeholder perceptions of a firm’s reputation rest in part on news coverage, only in 1990 was the first large-scale attempt made to test this assumption. Fombrun and Shanley (1990) focused on the amount and tone of the news. The frequency or visibility of the news is often used as a synonym for the amount of news, whereas nearsynonyms for the tone of the news are the tenor, direction, valence, or favorability of the news. The authors measured the amount and the tone of the news about firms by means of a content analysis of titles of newspaper articles. With firms as their units of analysis, they regressed the amount and the tone of the news about a firm, together with measures of its financial performance, on its reputation score. Reputations of firms were derived from the Fortune 500 survey among the business elite. They found that the amount of news had a negative effect, i.e., the greater the scrutiny of the firm by the press, the worse its reputation. On the other hand, the tone of the news had a significant positive effect on corporate reputation, but only for highly diversified firms, especially when the amount of news was large. Stakeholders may have to rely on the news for their information about diversified firms, because it is hard to deduce the reputation of such a firm from elementary knowledge about its core business. Later studies applied other research designs with mixed results. On the basis of a longitudinal research design with yearly data for three firms, Vercic (2000), for example, found that the yearly change in the amount or tone of the news did not have a significant effect on the yearly change in the perceived trustworthiness of the firm. In addition to different research designs, different operationalizations of a positive and a negative tone may have been at the heart of these mixed results.

News-Type-Specific Influences

Recent studies have found that media influence depends in addition on the “news frame,” the “news type,” or the “attributes” with which an organization is associated in the news. Among other things, the news may associate organizations with problems or “issues” that arise, with its successes and failures, or with stakeholders who are either supportive or critical of the organization. Each of these three news types (or “frames”) has a unique effect on the audience (Meijer 2004).

In issue news (e.g., !Philips rolls out sales of energy-efficient light bulbs”) an actor (e.g., Philips) promotes or counteracts an issue (e.g., sales of energy-efficient light bulbs). Research on second-level agenda setting and priming shows that the issues with which an organization is associated in the news become salient for evaluation of the organization (Carroll & McCombs 2003; Carroll 2004). On the basis of a correlational second-level agenda-setting study, starting from a 2005 content analysis of press releases and media coverage and aggregated survey data for 28 companies, Kiousis et al. (2007) concluded that a company’s attention to issues (or “substantive attributes”) in PR messages is transferred to the media agenda, and subsequently to public opinion. Moreover, media adopt the positive or negative issue positions of corporations from the PR news wire. Thus, firms are often quite successful in building the issues that serve to evaluate them.

Priming and second-level agenda setting occur also in a business context. Fombrun and Shanley’s (1990) early results point to the special status of issues related to a company’s core business, often labeled as owned issues in the political communication literature. In a study based on a yearly panel survey study and a daily content analysis of the news, 1997–2000, Meijer and Kleinnijenhuis (2006), for example, found that news about a firm’s owned issues did indeed increase reputation, even when controlling for former reputation. For example, the reputation of oil company Shell deteriorated in the eyes of audience members who came to associate the company with environmental issues, whereas its reputation improved for audience members who came to associate Shell with its core business. A respondent’s issue associations with Shell depended on issue associations with the company in the media from the respondent’s personal media palette. Remarkably enough, Shell raised environmental issues itself, because the company wanted to improve its environmental reputation actively after the 1995 Brent Spar affair, in which Greenpeace had successfully accused Shell of using the sea as a trash can to dump the obsolete Brent Spar oil platform.

Corporate reputations depend in a quite different way on news about corporate success and failure (e.g., “Upbeat forecast for Philips profits,” “Sales dip for Philips”). A defining feature of news about success and failure is that the subject that caused successes and gains or failures and losses remains unspecified. Success breeds success, according to Meijer on the basis of a panel survey study that permitted control for a firm’s previous successes (Meijer 2004). For example, most shareholders will follow market hype, whereas only highly aware shareholders will have the self-confidence to act against the hype (e.g., selling shares in a booming market, buying shares in a collapsing market).

Effects Of Support And Criticism From Stakeholders In The News

The literature shows mixed results with regard to effects of news about support and criticism. Whether criticisms hit home also depends on stakeholder credibility. Shah et al. (2002), for example, found that President Clinton was able to restore his reputation after the Monica Lewinsky affair once the moral issue disappeared and press reports came to focus on Republican hardliners who criticized Clinton. Republicans were never deemed credible by Democrats.

The variety of different stakeholders and experts in business news is quite impressive. Business news involves different issue arenas (e.g., corporate finance, mergers and acquisitions, labor relations, consumer affairs), each of them with its own stakeholders and its own experts. In news about mergers and acquisitions, for example, the news may start with rumors, but CEOs usually become the primary definers of the news. Financial analysts and bankers often play the role of experts in this type of news. But if, for example, dismissals are at stake, then employees will easily become the primary definers. Labor unions and a firm’s PR spokespersons often will enter the scene also, as will lawyers when the labor dispute is not settled soon. If a firm is prosecuted because of its violations of the law, then CEO and PR spokespersons, as well as lawyers and polling agencies, are likely to become newsworthy. If interest groups, e.g., environmentalists, become the primary definers in the news, then the responsibility for the defense is often with the PR department. In sum, each issue arena raises in the press its own primary definers, adversaries, and experts, whose antagonisms maintain the issue arena to the detriment of other such arenas.

The large number of more or less credible stakeholders in the PR domain makes a precise account of news about their support and criticism difficult, but studies to trace stakeholders are a first step. In their study about the growing prominence of CEOs in corporate news, Park and Berger (2004) found that CEO statements were counterbalanced with stakeholder statements. Stakeholders often cited in CEO press coverage were adversaries (e.g., other executives, board members, union personnel). But experts (e.g., financial analysts, industry analysts, scholars) were cited even more in news items about CEOs.

References:

- Carroll, C. E. (2004). How the mass media influence perceptions of corporate reputation: Exploring agenda-setting effects within business news coverage. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Austin, University of Texas.

- Carroll, C. E., & McCombs, M. (2003). Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public’s images and opinions about major corporations. Corporate Reputation Review, 16(1), 36–46.

- Fombrun, C. J., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 233–258.

- Kiousis, S., Popescu, C., & Mitrook, M. (2007). Understanding influence on corporate reputation: An examination of public relations efforts, media coverage, public opinion, and financial performance from an agenda-building and agenda-setting perspective. Journal of Public Relations Research, 19, 147–165.

- Meijer, M.-M. (2004). Does success breed success? Effects of news and advertising on corporate reputation. Amsterdam: Aksant.

- Meijer, M.-M., & Kleinnijenhuis, J. (2006). Issue news and corporate reputation: Applying the theories of agenda setting and issue ownership in the field of business communication. Journal of Communication, 56(3), 543–559.

- Park, D. J., & Berger, B. K. (2004). The presentation of CEOs in the press, 1990–2000: Increasing salience, positive valence, and a focus on competency and personal dimensions of image. Journal of Public Relations Research, 16, 93–125.

- Shah, D. V., Watts, M. D., Domke, D., & Fan, D. P. (2002). News framing and cueing of issue regimes: Explaining Clinton’s public approval in spite of scandal. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66, 339–370.

- Vercic, D. (2000). Trust in organisations: A study of the relations between media coverage, public perceptions and profitability. Unpublished PhD dissertation, London, London School of Economics and Political Science.