The intereffication model focuses on the relationship between public relations (PR) and journalism (Bentele et al. 1997). It was designed in a research project in 1996 – 1997 that focused on the PR activities of two East German cities, Leipzig and Halle. Unlike the determination hypothesis, the intereffication model stresses the interconnectedness of PR and journalism. The authors describe the model as a complex relationship of mutual influence, mutual orientation, and mutual dependence. Intereffication means that neither PR nor journalism would be able to function properly without the existence of the other (Latin efficare = to make possible). The authors invented the word intereffication in order to create a neutral term, one free of the connotations associated with more metaphorical terms like symbiosis and Siamese twins.

The Model

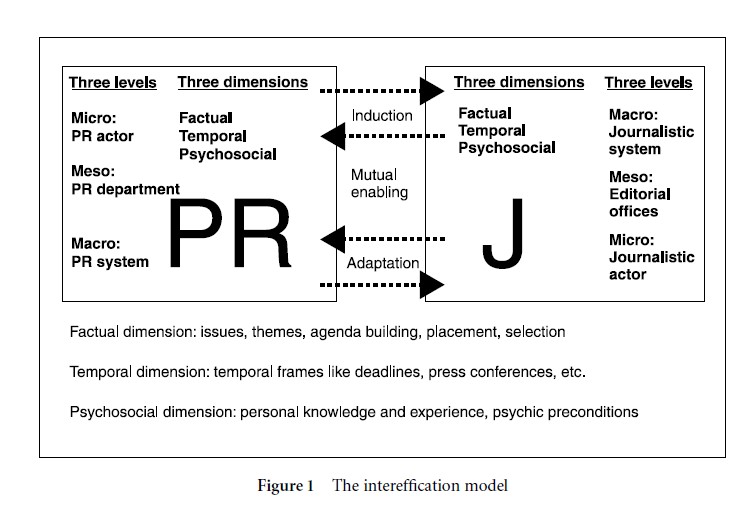

The model describes the mutual processes going on between PR and journalism as “adaptation” and “induction.” Adaptation, on the one hand, means that one system orients its activities and routines toward the other system in order to successfully place its messages. Adaptation can be defined as “communicative and organizational processes of adjustment” (Bentele & Nothhaft 2007). In order to be more successful in placing topics, actors like PR practitioners or entire PR departments adapt themselves to environmental constraints. Processes, on the other hand, that are able to influence the other system are called induction. Inductions are defined as “intended and directed communicative stimuli which result in observable resonances in the respective other system” (Bentele et al. 1997, 241). Resonances can be observed and partly measured as, for instance, media coverage (PR-induced coverage).

Both induction and adaptation happen in three dimensions: factual, temporal, and psychosocial. The psychosocial dimension consists of journalists’ and PR practitioners’ personal relationships. From a micro-perspective, it is important for both journalists and PR practitioners to know each other personally so that each can anticipate how the other will react to specific messages or questions. Gaining trust is another process in this dimension. Gaining trust is possible through a continuous flow of correct information and interaction only. If, on the one hand, PR managers lie, their trustworthiness is lost. Betrayed journalists will no longer believe them. On the other hand, journalists lose their trustworthiness if they do not report the entire story but pick up only a certain part that looks sensational.

In the temporal dimension, PR practitioners orient their timing toward the routines of journalism. For example, knowing the editorial deadline is important for sending out press releases and for arranging press conferences. This example shows that adaptations and inductions form two sides of the same coin: according to the model, the deadline itself is a journalistic induction, while keeping this deadline in mind and acting in line with journalistic routines are processes of adaptation. Journalists, in return, are more successful at getting information if they know the daily routines of PR managers. If a journalist knows that the PR manager of the biggest company in town usually has internal conferences from 9 to 11 a.m. and usually takes a lunch break from 1 to 2 p.m., then the journalist can anticipate the best time to call the manager.

In the factual dimension, sending out press releases is an inductive activity designed to influence the journalistic system. Press releases represent mainly thematic inductions. However, there are a lot more PR inductions in the factual dimension: press releases issued at conferences, facts and figures from annual reports, personal dialogues between PR practitioners and journalists, etc. Journalistic induction occurs when journalists select, place, assess, and comment on information. Another example of journalistic induction is when journalists force companies to hold an ad hoc press conference.

A great many adaptive processes go on in the factual dimension. Again, press releases are a good example: professional PR people write releases in a journalistic style according to routines like news factors or the “SIN” rule (the topic must be significant, interesting, and new), the inverted pyramid etc. Bentele and Nothhaft (2007) give an illustrative example of journalistic adaptation to PR routines and rules: journalists not only have to adapt to rules of accreditation and professional codes of conduct but also to the rules of war reporting such as the “embedding” of journalists into the operation “Iraqi Freedom”.

Figure 1 The intereffication model

According to the model, processes of adaptation and induction take place not only in three dimensions (psychosocial, temporal, factual) but also on three levels (Fig. 1). By looking at the mutual processes that go on between a journalist and a PR practitioner, the model describes the relationship of journalism and PR on the micro level, the level of individual actors. By focusing more on the level of PR departments’ editorial offices or entire media organizations, one switches to the meso level. The model also claims to be a sufficient framework on the macro level of functional social systems, but it is not necessarily in line with the latest macro models of systems theory (Schantel 2000).

Measurement And Findings

In recent years, the model has been employed in a number of research projects, mostly dissertations or master’s theses. Bentele and Nothhaft (2004, 2007) have summarized the major findings. The model was initially tested in the field of local politics. Subsequent studies applied the model in regional politics (Donsbach & Wenzel 2002) as well as in the fields of business and of labor unions. Unfortunately this research does not cover all of the model’s dimensions. As with the empirical research in the tradition of the determination hypothesis, these projects – as well as the master’s theses summarized by Bentele and Nothhaft (2004, 2007) – operate from a PR-centered perspective. They analyze the relation of PR-induced coverage to editorially induced coverage (input–output studies) with regard to single organizations (such as the regional German broadcasting station MDR) or certain areas of interest (such as politics in Saxony). Like Baerns’ (1979) study (the determination hypothesis), most of the studies show that roughly two-thirds of the analyzed articles are PR-induced. However, more than half of these PR-induced articles are not induced by press releases but by other PR activity. Other PR activity means, for example, a reference to a press conference in the text of the article. It is obvious that the data here are not unambiguous. Given that uncertain cases were treated as not induced by PR, there is evidence for a substantial influence of PR on journalism. However, this research tradition shows that the design of the research has a major impact on the results.

As Baerns’s determination thesis postulates that PR determines not only the topics but also the timing of media coverage (Baerns 1991, 98), most of the empirical research projects also analyzed the temporal dimension. To determine whether PR is able to influence the timing of media coverage, one has to measure the time between the PR activity and the media coverage. The data show that daily newspapers utilize the majority of press releases within three days of receiving them.

Critiques

There is still a lack of empirical research that covers the full range of the model. By using a PR-centered operationalization, most research labeled as intereffication is little more than modern determination research. Furthermore, personal or social factors that are the core of the psychosocial dimension are rarely analyzed. This lack of analysis is as much regrettable as it is understandable given the difficulties of measuring this dimension. Complex personal observation studies would be needed to gather data on this dimension. Research that focuses on journalistic induction and adaptation is also missing. The model should be broadened in three dimensions. First, the recipient should be included. This could improve the model through describing the entire process of agenda building and agenda setting. Second, the economic impact of the relationship between journalism and PR, which can affect inductions and adaptations in all dimensions of the model, should be integrated. Third, the model could be linked with frame analysis: shared frames or conflicting frames would suggest how the data/information might be interpreted and reported differently, and might even cause relationships to deteriorate.

References:

- Baerns, B. (1979). Öffentlichkeitsarbeit als Determinante journalistischer Informationsleistungen. [Public relations as a determinant of journalistic information]. Publizistik, 24(3), 301–316.

- Baerns, B. (1991). Öffentlichkeitsarbeit oder Journalismus? Zum Einfluß im Mediensystem. Cologne: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik.

- Bentele, G., & Nothhaft, H. (2004). Das Intereffikationsmodell. Theoretische Weiterentwicklung, empirische Konkretisierung und Desiderate [The intereffication model: Theoretical progress, empirical concretions and desiderata]. In K.-D. Altmeppen, U. Röttger, & G. Bentele (eds.), Schwierige Verhältnisse. Interdependenzen zwischen Journalismus und PR [Difficult relationships: Interdependencies between journalism and PR]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 67–104.

- Bentele, G., & Nothhaft, H. (2007). The intereffication model: Theoretical discussions and empirical research. In B. Merkel & S. Ruß-Mohl (eds.), A complicated, antagonistic and symbiotic affair: Journalism, public relations and their struggle for public attention. Lugano: Giampiero Casagrando, pp. 59 –77.

- Bentele, G., Liebert, T., & Seeling, S. (1997). Von der Determination zur Intereffikation. Ein integriertes Modell zum Verhältnis von Public Relations und Journalismus [From determination to intereffication: An integrated model of public relations and journalism]. In G. Bentele & M. Haller (eds.), Aktuelle Entstehung von Öffentlichkeit. Akteure, Strukturen, Veränderungen [The ongoing formation of the public sphere]. Constance: UVK, pp. 225 –250.

- Donsbach, W., & Wenzel, A. (2002). Aktivität und Passivität von Journalisten gegenüber parlamentarischer Pressearbeit [Journalists’ activity and passivity in facing a parliament’s public relations]. Publizistik, 47(4), 373 –387.

- Schantel, A. (2000). Determination oder Intereffikation? Eine Metaanalyse der Hypothesen zur PRJournalismus-Beziehung [Determination or intereffication? A meta-analysis of hypotheses about the relationship between public relations and journalism]. Publizistik, 45(1), 70 – 88.