Interest in the relationship between group communication and group problem-solving performance has a long and somewhat controversial history. Many trace interest in problem-solving in the group context back to the early work of Maximilian Ringelmann (1861–1931). Ringelmann first measured the effort of a single individual working alone, then measured how much more effort was achieved by two, and then three, people working together. He found that the triad exerted the most effort, but the intriguing aspect of this finding was that the addition of each person did not increase the performance by the average effort of a single individual. Triads, for example, only exerted 2.5 times more effort than individuals working alone. In short, Ringelmann discovered an inverse relationship between the number of people in a group and the magnitude of individual performance on additive tasks. This finding contradicts the notion that groups work harder than individuals, and became known as the Ringelmann effect. Subsequent work carried out by Ingham and colleagues (1974) essentially replicated Ringelmann’s original findings.

Since the days of Ringelmann, group interaction and communication have taken on increasing importance in the study of group problem-solving effectiveness. The presumed importance of group interaction is clearly implied in Steiner’s (1972) oft-cited formula: “Actual productivity = potential productivity – losses due to faulty processes.” This formula highlights the potential for communication to detract from the effectiveness of group problem-solving, though research suggests that some communication in problem-solving groups also contributes to the effectiveness of the group effort.

Definitional Parameters

Problem-Solving Group

Group scholars have historically defined a problem-solving group as a collection of individuals who interact with one another in their efforts to arrive at a solution for an unmet need or objective. The literature differentiates between two types of group problem-solving tasks: intellective tasks and decision-making tasks. Intellective tasks require a group to choose an alternative whose “correctness” can be determined by applying culturally accepted standards of coherence and rules of logic. Decision-making tasks, on the other hand, require a group to select an alternative whose “correctness” is determined by a “consensus about what is morally right or what is to be preferred” (McGrath 1984, 64). In short, groups working on intellective tasks produce outcomes that can be proven (objectively) to be of high quality, whereas groups working on decision-making tasks produce outcomes that can only be judged (subjectively) to be of high quality.

Group Communication

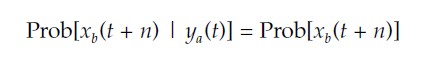

The terms “interaction” and “communication” are often used synonymously in the group problem-solving literature, but there are technical differences worth noting. Group interaction occurs when two or more group members do something together. As such, interaction involves mutual influence; that is, the behavior of one member (A), verbal or nonverbal, is affected by (because it is usually a response to) the behavior of another member (B, C, and so forth) and vice versa. Hewes (1996) uses the following equation to present a formalized, and widely accepted, definition of group interaction:

That is, interaction is said to occur in a group when the likelihood (Prob) of person B’s (b) overt physical/symbolic activity or behavior (x) at any given time (t + n), given the presence of person A’s (a) overt physical/symbolic activity or behavior ( y) at some prior point (t), does not equal the likelihood that person B would produce behavior x in the absence of person A’s behavior y. Stated in simple terms, interaction is said to occur between persons A and B when person A’s activitity has an influence on person B’s activity, and vice versa.

Communication, in contrast, refers to the achievement of common (or shared) understanding among two or more interacting individuals in regards to the meaning (or referent) of symbolic behaviors – verbal or otherwise – produced and exchanged by those group members. To the extent that communication and interaction are obviously inextricably intertwined, many group scholars tend to view the terms as synonymous, and hence use them interchangeably.

General Findings

Research shows that group communication affects group problem-solving performance in at least three general ways.

First, communication allows group members to distribute and pool available informational resources necessary for effective decision-making and problem-solving. Studies have found that group communication is especially important for successful group problem-solving when the group is characterized by the unequal distribution of crucial information. In particular, group discussion facilitates effective group performance when it results in the effective centralization of information in the hands of people who need it to help the group arrive at a high-quality decision (Stasser 1992).

Second, group communication allows group members to catch and remedy errors of individual judgment. According to Taylor and Faust (1952), the principal reason why groups generally outperform individual problem-solvers is because the discussion of ideas, suggestions, and rationales for preferred choices tends to expose informational, judgmental, and reasoning deficiencies within individual members that might go undetected if those individuals were solving problems on their own. Moreover, group discussion provides the opportunity for members to point out and correct these problems before they can contribute to regrettable choices.

Third, group communication serves as a means for intragroup persuasion. Shaw and Penrod (1962) found that group discussion provides members with the opportunity to present and support their decisional preferences and, in so doing, convince others to go along with those alternatives. According to Riecken (1958), the overall quality of a group’s solution will often depend on the solution preference of the group’s most persuasive member(s). His findings indicate that the presence of knowledgeable group members does not necessarily lead to high levels of group performance unless those individuals are able to persuade others to accept and utilize the information they possess in arriving at a group decision.

Findings Regarding Group Communication And Problem-Solving

While research provides evidence that group communication is related to group problem-solving performance, the available evidence suggests that the relationship is more complex than initially believed. Studies show that group communication is more than a convenient channel that group members use to distribute information or make their preferences known to others in the group. Communication appears to have its own distorting and biasing effects on group problem-solving performance (Hirokawa 2003), and the relationship between group communication and group problem-solving performance seems to be affected by at least two task-related contextual factors: (1) information distribution, and (2) information-processing requirements (Orlitzky & Hirokawa 2001; Hirokawa 1996).

The relationship between group interaction and group problem-solving perfromance appears to be affected by the distribution of relevant information among group members (Hirokawa 1990). When information is equally distributed among group members, communication appears to be unrelated to group problem-solving performance (Leavitt 1951). However, when the distribution of information is skewed so that only a few group members possess the information needed to solve the problem, a positive relationship between group communication and group problem-solving performance emerges (Shaw 1964).

The relationship between group communication and group problem-solving performance also appears to be influenced by the information-processing requirements of the problem-solving task. Information-processing requirements refer to the extent to which (1) the validity or accuracy of relevant information can be objectively verified, and (2) the relevance of available information is clearly evident to group members. Research indicates that group communication is unrelated to group performance when information processing requirements are low – that is, when the accuracy of information can be verified, and when the relevancy of the information is clear (Argyle & Cook 1976; Williams 1977). When information-processing requirements are high, however, a positive relationship between group communication and group problem-solving performance emerges (Hiltz et al. 1986).

In summary, we can expect group communication to have the greatest impact on group problem-solving performance when the group task is characterized by unequal information distribution and high information-processing requirements. Under other circumstances, the relationship between group communication and group problem-solving performance remains less clear.

References:

- Argyle, M., & Cook, M. (1976). Gaze and mutual gaze. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Hewes, D. E. (1996). Small group communication may not influence decision making: An amplification of socio-egocentric theory. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (eds.), Communication and group decision-making, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 179 –214.

- Hiltz, S. R., Johnson, K., & Turoff, M. (1986). Experiments in group decision-making: Communication process and outcome in face-to-face versus computerized conferences. Human Communication Research, 13, 225 –252.

- Hirokawa, R. Y. (1990). The role of communication in group decision-making efficacy: A taskcontingency perspective. Small Group Research, 21, 190 –204.

- Hirokawa, R. Y. (1996). Communication and group decision-making effectiveness. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (eds.), Communication and group decision-making, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 269 –300.

- Hirokawa, R. Y. (2003). Communication and group decision-making efficacy. In R. Y. Hirokawa, R. S. Cathcart, L. A. Samovar, & L. D. Henman (eds.), Small group communication: Theory and practice, 8th edn. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury, pp. 125 –133.

- Ingham, A. G., Levinger, G., Graves, J., & Peckham, V. (1974). The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 371–384.

- Leavitt, H. J. (1951). Some effects of certain communication patterns on group performance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46, 38 –50.

- McGrath, J. E. (1984). Groups: Interaction and performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Orlitzky, M., & Hirokawa, R. Y. (2001). To err is human, to correct for it divine: A meta-analysis of research testing the functional theory of group decision-making effectiveness. Small Group Research, 32, 313 –341.

- Riecken, H. W. (1958). The effects of talkativeness on ability to influence group solutions to problems. Sociometry, 21, 309 –321.

- Shaw, M. E. (1964). Communication networks. In L. Berkowitz (ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 1. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Shaw, M. E., & Penrod, W. T. (1962). Does more information available to a group always improve group performance? Sociometry, 25, 377–390.

- Stasser, G. (1992). Pooling of unshared information during group discussion. In S. Worchel, W. Wood, & J. Simpson (eds.), Group process and productivity. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, pp. 48 –57.

- Steiner, I. D. (1972). Group process and productivity. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Taylor, D. W., & Faust, W. L. (1952). Twenty questions: Efficiency in problem solving as a function of size of group. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 44, 360 –368.

- Williams, E. (1977). Experimental comparisons of face-to-face and mediated communication: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 963 – 976.