The term “language varieties” covers “language” and “dialect.” A variety may be characteristic of a particular social group, or associated with a particular speaking style across groups of speakers in a community. “Variety” makes no direct or indirect assertions about the relative status of the linguistic system being described (“dialect” often refers with negative overtones to nonstandardized varieties).

The relationship between language, social groups, and styles reflects present-day and historical factors that are unique to each community. Good variationists use qualitative research to decide which correspondences between language and society to examine quantitatively. Some social groupings are common across societies, presumably because such group distinctions are generally salient to people the world over. These include identities and networks based on age, gender, social class, or very local communities of practice. Speakers systematically, though often subconsciously, differentiate members of different social groups by using a wide range of linguistic resources. These can be subtly different pronunciations of the same words, different patterns for organizing new and old information in sentences, or different pitch and intonation patterns. In earlier work on sociolinguistic variation, these correspondences were sometimes discussed as if the social categories with which speakers could be identified determined their use of particular linguistic variants. This is viewed critically now, and the relationship between linguistic forms and social identities is considered to be more complex, and mutually constitutive.

William Labov, considered the founder of variationist studies of language, demonstrated that variation of a feature of talk (e.g., gonna vs going) may not be categorical, but is systematically and probabilistically constrained by linguistic and social factors. (In most linguistic variables, the linguistic constraints account for more of the observed variation than social or individual factors do.) This means that synchronic variation, i.e., that which occurs at a particular moment in time, can be studied as a complement to historical linguistics.

Not all linguistic variation is the first step in language change. Some variables are stable over time. Stable variables and changes in progress have different profiles across different age groups of speakers. Variationists infer change from differences in the distribution of variants across different age groups (“apparent” or “generational” time as opposed to real/ chronological time). The robustness of apparent time has been validated by real-time checks of some studies. For changes proceeding below speakers’ conscious awareness, apparent time seems to be reliable. However, apparent time data are not good indicators of the speed with which a change is taking place.

More conservative variants are often retained in formal or careful speech styles longer than they are retained in informal or casual speech. Sociolinguists differ in how they understand individual style. Labov argued for a model based on whether a speaker was giving more or less attention to the act of speaking. Howard Giles argued that style shifting reflected different (real or imagined) addressees, to whom the speaker was converging (accommodating), and Allan Bell developed this further as “audience design.”

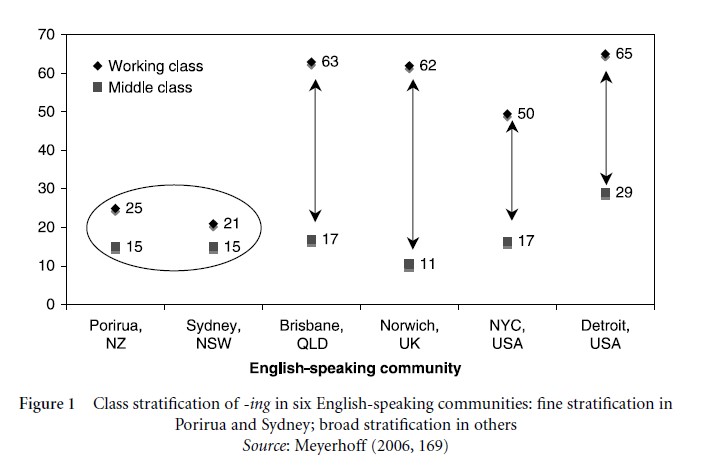

There are often striking parallels between the way variants are distributed across individuals’ styles of speaking and across different social classes. Typically, the variant that occurs most in more casual styles, or more ingroup speech, also occurs more often as one moves down the social spectrum. For example, the suffix “-ing” (“walking~walkin”) occurs as “-in” most in working class speech overall, and most in all classes’ casual ingroup style. The parallelism between class and style suggests that ideologies about class and style (whether operationalized as attention to speech or attention to others) are very deeply intertwined.

Figure 1 Class stratification of -ing in six English-speaking communities: fine stratification in Porirua and Sydney; broad stratification in others

Figure 1 Class stratification of -ing in six English-speaking communities: fine stratification in Porirua and Sydney; broad stratification in others

It has been suggested that broad social class stratification (i.e., major differences in relative frequency of a variant in the speech of different social classes) reflects relatively rigid social class divisions at the societal level. However, evidence supporting this is limited (Fig. 1). The fine stratification observed in New Zealand and in Sydney might fit with Australasian ideologies of social mobility, but we find similar patterns of broad social class stratification in Brisbane as we do in Norwich (UK) and Detroit (USA).

References:

- Eckert, P. (2000). Linguistic variation as social practice. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Labov, W. (1994). Principles of linguistic change, vol. 1: Internal factors. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Labov, W. (2001). Principles of linguistic change, vol. 2: Social factors. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Meyerhoff, M. (2006). Introducing sociolinguistics. London: Routledge.

- Sankoff, G. (2006). Apparent time and real time. In K. Brown (ed.), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, vol. 1, 2nd edn. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 110–116.

- Shepard, C., Giles, H., & Le Poire, B. A. (2001). Communication accommodation theory. In W. P. Robinson & H. Giles (eds.), The new handbook of language and social psychology. Chichester: Wiley, pp. 33–56.

- Wolfram, W., & Schilling-Estes, N. (2005). American English: Dialects and variation. Oxford: Blackwell.