An important concept to apply in describing how journalists in different cultures and media systems understand their work and its social function is role perceptions. These can have a strong influence on journalists’ professional behavior and thus can explain differences between news cultures. The term “role” originates from theater, and sociology adopted the term to designate the whole set of expectations that other people have of the holder of a certain social position. Those expectations then create the perceptions that the holders of the roles have in their social environment and accept as legitimate, and consequently their perceptions guide their attitudes and behaviors. Thus, journalists’ role perceptions can be defined as generalized expectations which journalists believe exist in society and among different stakeholders, which they see as normatively acceptable, and which influence their behavior on the job.

Journalists’ role perceptions have been studied primarily for news workers involved in covering politics and current affairs. The research assumes that the way journalists understand their role will influence considerably the way they interact with news sources and make decisions about news selection and presentation. In a causal model of factors influencing news decisions, role perceptions become an intervening variable that moderates the influence of primary variables such as the news value of people or topics in the news, or subjective beliefs. For instance, journalists who see themselves as a common carrier of the news might try to suppress the influence of their own preferences on the coverage of a political figure. Conversely, journalists who see a role for themselves in political activism would allow such a subjective influence.

Theoretical Concepts

To describe journalists’ role perceptions, communication researchers have developed a variety of concepts, some as ideal types, some as normative standards, and some as empirical typologies. According to sociologist Max Weber, ideal types develop from observing reality but do not exist in reality in their pure form. They usually occupy the end points of a given dimension and thus form helpful markers. Siebert et al. (1956) presented the first spectrum of this kind in their four theories of the press: the authoritarian, the Soviet, the liberal, and the socially responsible. Although used to distinguish between press systems, these four theories can also be regarded as ideal-type descriptions of different journalistic role perceptions.

One of the most widely recognized pairs of ideal types for role perceptions was identified by Morris Janowitz (1975), who distinguished between the gatekeeper and the advocate. These types differ particularly along two dimensions: their picture of the audience, and their patterns of news selection. Journalists adhering to the advocacy model may assume that many members of the audience cannot either recognize or pursue their own interests in society. These journalists therefore believe that their major task is to act on behalf of this part of the audience. Consequently, they select the news according to its instrumentality for the social groups they support. In contrast, the gatekeeper regards audience members as mature and able to pursue their own needs and thus selects the news exclusively according to professional criteria, such as the perceived news value. Similar but not identical is the distinction between the neutral and the participant journalist (Johnstone et al. 1976) in a survey of US journalists. The active versus the passive journalist, the liberal versus the partisan journalist, and the mediator versus the communicator are similar ideal types.

Several normative typologies highlight specific social tasks that the public can or should expect journalists to perform. The typologies serve a heuristic purpose in research. For instance, Patterson (1995) distinguished between the roles of signaler, common carrier, watchdog, and public representative. As signalers, journalists represent an early warning system for society. As common carriers, they channel information between the government and the people. As watchdogs, they monitor institutions and issue warnings to the actors in politics and commerce, and as public representatives, they become spokespersons on behalf of public opinion.

Several normative proposals for journalistic role models have triggered discussions in the academic as well as in the professional world. In the 1960s and 1970s, several authors suggested a different and more active role for journalists in developing countries, arguing that the state of social structures and of the media system in such countries would require that journalists become themselves agents of change and collaborate to a certain extent with the authorities. In the USA a widely recognized debate about journalists’ professional tasks began with the proposal of the new role: public journalism. Although the term lacks a universally accepted definition, it usually assigns journalists the role of motivating or enhancing public deliberation and getting the public more engaged. Along a different dimension Philip Meyer (1991) suggested that journalists should see themselves more often in a role equivalent to that of the social scientist, applying research methods such as polls and statistical analyses of data sets to describe social reality.

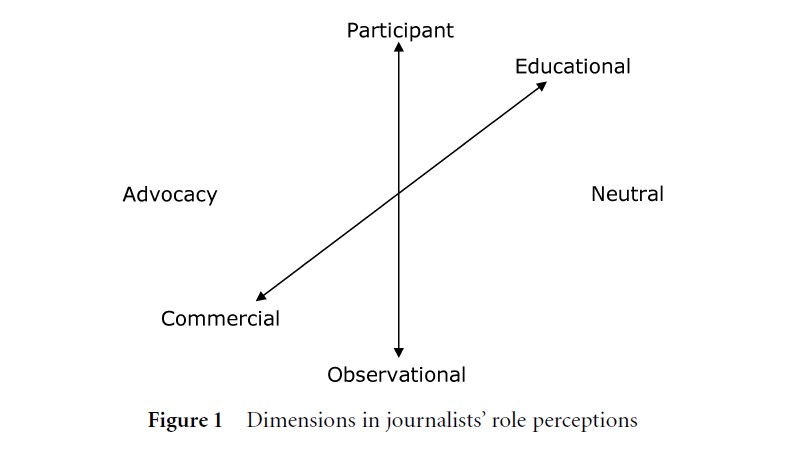

Figure 1 Dimensions in journalists’ role perceptions

Figure 1 Dimensions in journalists’ role perceptions

Finally, different patterns of role perceptions have emerged from surveys of journalists and subsequent data analyses, usually by factor analysis. In the first of a series of surveys of US journalists, Weaver and Wilhoit (1986) extracted from their data the roles of information dissemination, interpretative-investigative, and “adversary.” An international comparative survey of British and German reporters and editors (Köcher 1986) labeled the role perceptions of the German respondents as those of missionaries and the British as those of bloodhounds.

The common denominator of these typologies is that they ask what social goals journalists should pursue and how they should behave on the job when collecting and processing the news. For democratic countries, the existing theoretical role models differentiate three dimensions, all of them interrelated (see Fig. 1). On the first dimension (participant–observational), journalists can choose between actively seeking to influence the political process and trying to function as impartial conduits for political reporting. On the second dimension (advocacy–neutral), the alternatives are expressing subjective values and beliefs and maintaining strict neutrality and fairness to all sides. Finally, on the third (commercial–educational), journalists can strive either to reach the widest audience by serving its tastes and patterns of media exposure or to make news decisions based on what is good for democracy and public discourse. Journalists in all countries acquire elements of all these dimensions from the available role models. Scholars can usually explain the differences between journalistic cultures when comparing countries or between individual journalists in a single country by examining which of the alternatives prevails.

Emergence Of Role Perceptions

How journalists perceive their professional role depends on many factors, including the collective influence of the professional culture of a given country, the individual influence of other journalists, or both. Historical development is one of the most decisive factors for differences in journalism between countries. For instance, economic and social changes in the US population in the first half of the nineteenth century, as well as the commercial motivation of publishers to reach the widest possible audience, together drove US newspapers to adopt a less partisan position, to become oriented more toward news and less toward opinion, and to develop basic professional standards such as the norm of objectivity. It was “the triumph of the news over the editorial and facts over opinion, a change which was shaped by the expansion of democracy and the market, and which would lead, in time, to the journalist’s uneasy allegiance to objectivity” (Schudson 1978, 14). The role model of a neutral observer of ongoing social and political processes still permeates today the way most US journalists see and carry out their job.

Journalism in the United Kingdom showed similar patterns of historical development because of early press freedom and commercialization, but the professional role models in most of the continental European countries developed differently. In Germany, for instance, the absence of press freedom until the twentieth century led journalists to see themselves as individual freedom fighters and adversaries of authority. As a consequence, many journalists consider it more important to voice their opinion than merely to cover the news.

The development of professional standards also influenced journalists’ role perceptions, often as a consequence of media history and the emergence of professional organizations, as did the training and socialization of journalists. While in some countries, such as the USA, a majority of journalists have studied a journalism or similar university program with standardized modules conveying specific professional norms, in most other countries news workers come from many different fields and lack a common basis of knowledge and norms. Aside from these intercultural differences, the role perception of journalists within a given media system can also differ according to their individual training, socialization, institutional demands, or personal job motivations.

Measurement And Findings

Communication researchers have applied a variety of methods and empirical indicators to assess journalists’ role perceptions. Surveys in which the respondents answer questions about their norms and behaviors are the method used most frequently by far. Analyses of media content allow researchers to infer role perceptions from the work product. Participant observation in the newsroom allows researchers to witness the behavior of journalists on the job in day-to-day practice.

Most frequently researchers have asked explicitly how journalists define their roles or tasks, for example whether they see themselves as neutral reporters or as proponents of specific values and ideas. Questions about journalists’ general motivations in their work can reveal their ambitions, that is, which goals they want to pursue while working in journalism. Questions about qualifications and skills necessary to do the job well can indicate where journalists see the core competence of the profession. Questions about basic norms such as fairness, objectivity, or distance from sources can reveal the normative basis of their practice. Questions on their picture of the audience can show whether they see themselves in a position elevated above or equal to the public, which in turn can indicate an educational role perception.

Comparative investigations are particularly valuable because they allow benchmarking with other professional cultures and can help interpret and evaluate the role perceptions measured in one country or in one professional sector. Although journalists in western democratic societies operate under similar legal, political, economic, and cultural conditions and share a professional orientation, their media systems, news organizations, political structures, and general cultures differ and thus affect their norms and behaviors. International comparative research on journalists’ role perceptions began with the so-called professionalization studies that Jack McLeod and colleagues initiated in the 1960s. The researchers had developed a scale for measuring how the professional attitudes of US journalists compared to those of traditional professions such as medicine and law. Surveys later applied the scale to journalists from other countries, allowing international comparisons (Donsbach 1981). Several other research programs contributed to comparative evidence on role perceptions. A questionnaire first used for US journalists in the 1980s was later applied in 20 other countries (Weaver 1997). In the early 1990s a survey conducted almost simultaneously in five countries measured the role perceptions and professional norms of journalists involved in daily news decisions (Donsbach & Patterson 2004).

These international comparative studies show that professional cultures differ considerably even among countries otherwise similar in the structural patterns of their media and political organization. In the study of journalists mentioned previously, German and Italian respondents said far more often than their British, Swedish, and US colleagues that “championing values and ideas” was an important aspect of their work as journalists, thus indicating a role perception more open to advocacy. German and Italian respondents rated professional standards such as objectivity or neutrality as less important and readiness to influence the political process as more important. For Germany, a higher advocacy role perception also clearly correlated with the influence of subjective beliefs on actual news decisions in a quasi-experimental design that accompanied the survey. These cross-national differences describe news systems that also have much in common, including their primary task: gathering and disseminating the latest information about current events. Western news systems are more alike than different, although their differences are important and consequential. Besides differences based on mean values for these countries, role perceptions can differ considerably among individual journalists and media organizations.

Role perceptions within the countries have also changed over the years. In some cases the changes have occurred through crucial events, such as the Vietnam War or the Watergate scandal in the USA, which made US journalists more skeptical or even cynical toward politics and political leaders. Content analysis of Swedish news media over a period of 80 years showed a sharp increase in negative news (Westerstahl & Johansson 1986), leading to the conclusion that the general role model of journalism changed in the 1960s from the ideology of paternalism to the ideology of criticism, and surveys and content analyses in other countries (Lang et al. 1993; Patterson 1993) support that interpretation. Some evidence suggests that the increasing commercialization of the news media worldwide has started yet another, more global process of changing role models, so that for many journalists the possibility of advocating specific goals and norms has become less important in the face of an increasing necessity to reach the widest audience. More evidence from empirical studies is needed, however, to verify this hypothesis.

References:

- Donsbach, W. (1981). Legitimacy through competence rather than value judgments: The concept of professionalization re-considered. Gazette, 27, 47– 67.

- Donsbach, W., & Patterson, T. E. (2004). Political news journalists: Partisanship, professionalism, and political roles in five countries. In F. Esser & B. Pfetsch (eds.), Comparing political communication: Theories, cases, and challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 251– 270.

- Janowitz, M. (1975). Professional models in journalism: The gatekeeper and the advocate. Journalism Quarterly, 52, 618 – 626.

- Johnstone, J. W. C., Slawski, E. J., & Bowman, W. W. (1976). The newspeople: A portrait of American journalists and their work. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Köcher, R. (1986). Bloodhounds or missionaries: Role definitions of German and British journalists. European Journal of Communication, 1, 43 – 64.

- Lang, K., Lang, G. E., Kepplinger, H. M., & Ehmig, S. (1993). Collective memory and political generations: A survey of German journalists. Political Communication, 10, 211–229.

- Meyer, P. (1991). The new precision journalism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Patterson, T. E. (1993). Out of order. New York: Knopf.

- Patterson, T. E. (1995). The American democracy, 7th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Schudson, M. (1978). Discovering the news: A social history of American newspapers. New York: Basic Books.

- Siebert, F., Petersen, T., & Schramm, W. (1956). Four theories of the press. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Weaver, D. H. (ed.) (1997). The global journalist: News people around the world. Cresskill, N J: Philip Seib.

- Weaver, D., & Wilhoit, G. C. (1986). The American journalist: A portrait of U.S. newspeople and their work. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Westerstahl, J., & Johansson, F. (1986). News ideologies as molders of domestic news. European Journal of Communication, 1, 133 –149.