Advertising is the key link in the mutually sustained global expansion of consumer goods and services industries and the media of communication that carry their commercial messages. In this structural context, advertising is much more than the images and brand names that form the surface of consumer culture. It is the life-blood of the media, and the motive force behind media industry development. Further, it is the publicly most visible dimension of marketing, that is, the cultural industry that seeks to connect the producers of consumer goods and services with their potential markets, and in fact, to bring those markets into being. This integrated institutional relationship between production and consumption, with the advertising agency at its center, may be referred to as the “manufacturing–marketing–media complex.”

Advertising agencies produce and place advertising for their “clients,” the consumer goods or service companies that are the actual advertisers (not just “manufacturers”). However, although the clients pay their “agents” for these services, agencies also derive income directly or indirectly from the media in the form of a sales commission paid in consideration of the media space and time, such as newspaper pages or television “spots,” that the agencies purchase on behalf of their clients.

From The Multinational To The Global Era

The period since World War II has seen the internationalization of the advertising industry proceed in tandem with the emergence of the “multinational,” now global, consumer goods corporation, as well as with the international expansion of new media by their capacity to carry commercial messages to audiences. US-based advertising agencies in particular were backed by “common account” agreements with their clients from their home market, that is, the advertisers would have the same agency act for them in all the foreign markets in which they were becoming active. As well as arriving with such clients, US agencies were able to quickly dominate the advertising industries of the countries they entered because of their experience with the relatively new medium of television, the advertising medium par excellence.

By the 1970s, the influx of US advertising agencies had provoked some local resistance, and they became one of the targets of the rhetoric against “cultural imperialism” in that decade. Subsequent expansion then had to proceed more through joint ventures in conjunction with national agencies. At this stage, internationalization was largely driven by US-based national corporations that built up a number of overseas subsidiaries and hence transformed themselves into “multinational” or “transnational” corporations. However, in the era of globalization, corporations no longer necessarily have a home in any one particular country, in terms of either their management or their capital investment. Globalization is marked by an interpenetration of different sources of capital and complexity of corporate structure and management that transcend any single national base. This is particularly well illustrated by the advertising industry, above all in the emergence of the “megagroups,” or groups of global advertising agencies.

Architecture Of The Global Advertising Industry

Megagroups are organizational and financial structures under which major international advertising agency networks, global corporations in themselves, have been consolidated so they can be coordinated at a higher level of management. This corporate architecture is probably unique to the advertising industry, as it arises from the history of the advertising business itself, and the patterns of growth it has assumed at the international level in recent decades.

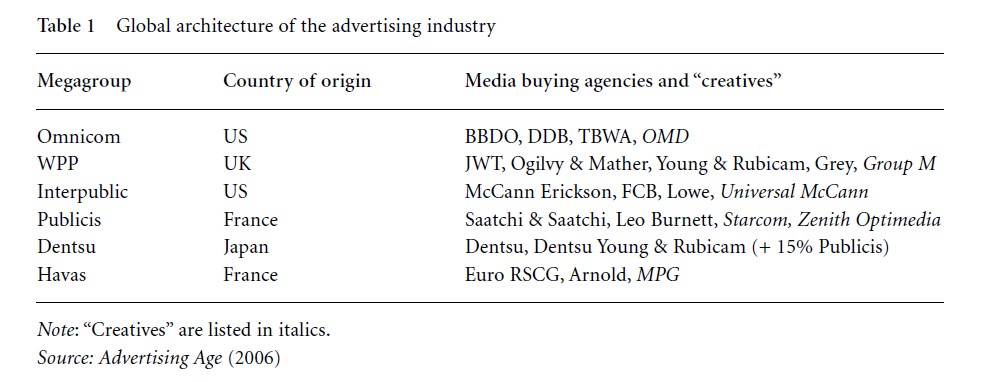

Although the very first of these groups to be formed was in the US in the 1960s (the Interpublic Group), it was the British agencies Saatchi & Saatchi and WPP that transformed the industry internationally in the 1980s. Advertising agencies had traditionally been owned by their principals and/or staff, but this imposed limits on their growth in the global era. What the British agencies did was to raise capital by making themselves into public companies, which then funded the acquisition of other agencies. Thus, WPP famously bought up two of the biggest and best-known US-based agencies, J. Walter Thompson (now JWT) in 1987 and Ogilvy & Mather in 1988. Around the same time, three big US agencies joined with each other to form Omnicom, while the French-based agencies Havas and Publicis also formed international groups in the 1990s.

Table 1 Global architecture of the advertising industry

Apart from the growth imperative, these epoch-making moves were motivated by the need to manage “client conflict” in a world in which the advertising industry was serving fewer but bigger clients on a global basis. Such advertisers do not tolerate a conflict of interest in which their advertising agency is also handling an account for one of their competitors. The global group is a solution to this problem – for example, Colgate and Unilever are competing clients, but the WPP group can keep them both, with Young & Rubicam handling Colgate, while Unilever goes through Ogilvy & Mather.

Table 1 summarizes the global architecture of the advertising industry, listing the groups in their order of size, as of mid-2006. The huge Japanese agency Dentsu has been included, for although it operates as a single agency, it has a share in Publicis, as well as a longstanding joint venture with Young & Rubicam.

The division of labor between the two key advertising functions of “creative” and media buying agencies has been consolidating in separate businesses over the last decade, that is, respectively, the production of advertising campaigns and the placing of advertising in the media. The former is more in accordance with everyday perceptions of what advertising agencies do, but the strategic purchase of media space and time by “media agencies” is the most traditional and consequential of the whole range of functions that specialized agencies now perform for clients. Thus, in addition, the global groups characteristically include companies in related marketing disciplines, such as public relations, and perhaps more specific forms of advertising, such as direct mail and, of increasing importance, “interactive” or Internet advertising.

Issues In Global Advertising

The first issue is the impact of trends in the advertising industry upon media development throughout the world. In an era in which advertisers have become more concerned to measure the results of their advertising expenditure, and skeptical about the ability of traditional media, especially broadcast television, to deliver such results, the flow of advertising expenditure toward new media, notably subscription television (“pay-TV”) and, more dramatically, the Internet, is undercutting the “mass” media we have known in the past. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that newer forms of commercialization are blurring the traditional line between advertising and information/entertainment content. Agencies are now assisting advertisers with producing “branded content,” and advising on product placement, sponsorship, and other forms of nonadvertising promotion via the media.

Even before the advent of the multichannel environment offered by pay-TV, we had entered a “post-broadcast” era in which media choices became much more tailored to individuals and less social. Following cable and direct satellite services, personal digital recorders (PDRs) have now appeared on the horizon, the latest in the spread of ever more interactive, mobile, and individuated modes or “platforms” for accessing audiovisual information and entertainment. For advertisers, this means ever more precise and personalized targeting of prospective consumers. The consequent drift to nonadvertising forms of promotion is tending to undermine the basic, traditional business model on which the relationship between advertisers and the media has rested since the advent of commercial broadcasting, namely, with the media amassing audiences for sale to advertisers, and instead, the trend will propel growth in new means of marketing delivery, particularly the mobile phone, the Internet, and interactive TV. This implies on the one hand a more fragmented society, but on the other, a more interactive relationship between producers and consumers.

Second, there are issues surrounding the relationships between advertisers and their agencies. This relates to the degree to which global advertisers dominate in a given national market, and still favor common account arrangements, now referred to as “global alignment.” Such a practice has the effect of locking out local or national agencies from ever winning the large, lucrative accounts of advertisers that are aligned globally with the global agencies, unless the local or national agencies themselves become affiliated with one of the global megagroups.

Either way, globalization is having an impact. However, also of interest is the precise pattern and extent of global–local interpenetration within the main agencies in a given country. The joint venture arrangements that characterized the 1970s continue to provide mutual benefits: the local agencies gain access to the global clients, while the global agency acquires local cultural knowledge. Yet perhaps it is no longer meaningful to distinguish between global and local agencies at all, in an era in which global agencies can make campaigns look local, and vice versa.

A third set of issues is more concerned with cultural questions of how advertisers and their agencies are approaching their markets. Of particular interest are the precise ways in which global products and advertising for them are being “glocalized,” that is, modified in accordance with local culture, including language. Contrary to theorists’ fears, global advertisers and agencies have not created a homogeneous world. Some inherently global products and services can be standardized, or advertised with the same global campaign in all markets, such as airlines. Most others require glocalization, or an even more tailored approach, taking account of not just national cultural differences, but religious or rural/urban differences. In this respect, we can see how culture, especially language and religion, forms a bastion against global advertising, but also how global advertising seeks to camouflage itself behind local cultures.

A fourth set of issues concerns the capacity of governments to properly regulate advertising in the global era, with its pressures for free trade and prevailing neo-liberal ideology favoring industry self-regulation, in spite of current public policy questions such as the role attributable to advertising in the problem of childhood obesity.

Problematics And Prospects

With the advent in social theory of poststructuralism and postmodernism, the diversification of feminism, and the eclipse of Marxism, much less attention is now paid to advertising than in the heyday of critical work on advertising in the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, there was a social science literature that tended more toward behavioral effects, while a political economy approach pursued the ownership and control of advertisers and their agencies, and analyzed their business strategies. Within a cultural studies or media studies perspective, there was a concentration on the cultural codes and ideological meanings of advertisements themselves as texts.

In contrast, recent theory and research have largely moved away from the study of advertising as such, and more toward consumer culture in general. In the process, there is also a useful fusion being achieved between the traditionally antagonistic camps of political economy and cultural studies, under the rubric of “cultural economy” (Jackson et al. 2000). There is also a recent “anthropological turn” developing, with anthropologists doing ethnographic fieldwork in advertising agencies, or among consumers and viewers of ads (Malefyt & Moeran 2003).

Although there has not been a truly comprehensive, internationally comparative, and historically contextualized work on the manufacturing–marketing–media complex since Armand Mattelart’s Advertising international of 1991, Frith and Mueller’s Advertising and societies: Global issues (2003) is a useful guide to the more recent literature.

References:

- Advertising Age (2006). World’s top 50 marketing organizations special report: Agencies profiles supplement, p. 3 (May 1).

- Frith, K., & Mueller, B. (2003). Advertising and societies: Global issues. New York: Peter Lang.

- Jackson, P., Lowe, M., Miller, D., & Mort, F. (eds.) (2000). Commercial cultures. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- Malefyt, T., & Moeran, B. (eds.) (2003). Advertising cultures. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- Mattelart, A. (1991). Advertising international. London: Routledge.