The goal of the extended parallel process model (EPPM) is to provide guidance on how to manage fear generated from communications about a threat. Fear is a powerful motivator, and the key to a successful communication about a threat is to channel this fear into a direction that promotes adaptive, self-protective actions, and prevents maladaptive, inhibiting, or self-defeating actions.

According to the EPPM, when people are faced with a threat they either control the danger or control their fear about the threat. The variables that cause individuals to either control the danger or control their fear are defined as follows. Perceived threat, or the degree to which we feel susceptible to a serious threat, is composed of two dimensions. The first, severity of threat, refers to the perceived seriousness of a threat or the magnitude of harm we think we might experience if the threat occurred (e.g., injury, loss, death, disgrace, etc.). For example, do you think contracting HIV is serious? Do you believe there would be harm if you did not prepare for a natural disaster? The second dimension, susceptibility to threat, is the perceived likelihood of experiencing a threat. For example, you might ask, am I at-risk for contracting HIV? How likely is it that a natural disaster will occur?

Perceived efficacy, or the degree to which we believe we can feasibly carry out a recommended response to avert a threat, is also composed of two dimensions. The first is response efficacy – our beliefs about whether or not a recommended response works in averting a threat. For example, do you think condoms prevent transmission of HIV? Do you think preparation will mitigate harm from a natural disaster? The second, self-efficacy, is beliefs about our ability to perform the recommended response. For example, do you feel able to use condoms to prevent HIV transmission? Is it feasible for you to prepare for a natural disaster?

Theoretical Predictions

Research has shown that perceptions of threat and perceptions of efficacy jointly influence behaviors such that one of three responses occur – no response to the message, a fear control response, or a danger control response.

When perceived threat is low, there is no response to the message. If a threat is believed to be trivial or irrelevant to a person, then individuals simply ignore any communication about a threat. For example, if people hear about a polio outbreak in China but live in Ethiopia, then they will perceive the threat to be irrelevant to them and they will not pay any attention to messages about polio (an example of low perceived susceptibility). Similarly, if there is a flu outbreak in Ethiopia, but people do not think of the flu as being serious, then they will not respond to a message about the flu because it is of so little priority in their lives (an example of low perceived severity).

In contrast, when people perceive a threat, they are motivated to act. The greater the threat perceived, the more motivated we are to do something (anything!) to get rid of the negative feelings caused by the fear arousal. That is, the more serious we believe a threat to be and the more vulnerable we feel toward that threat, the greater the fear aroused, and the greater the motivation to do something. Thus, when individuals feel susceptible to a serious threat, they are motivated to act.

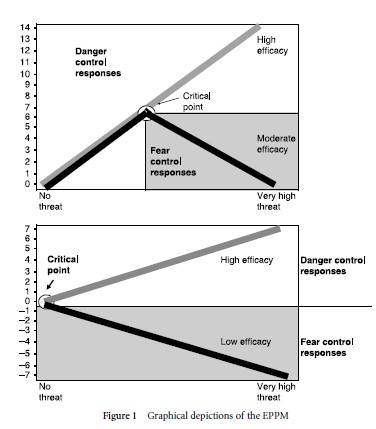

Perceived efficacy determines what type of action is taken. Once motivated to act, perceived efficacy about recommended responses determines whether we will control the danger or control our fear. When perceived efficacy is high, i.e., people believe they are able to do a recommended response that effectively averts the threat, then they are motivated to control the danger and they adopt the recommended action. In contrast, when perceived efficacy is low, i.e., people doubt if they are able to do a recommended response and/or they believe the recommended response to be ineffective against the threat, then they turn instead to controlling their fear and engage in psychological defense mechanisms like denial (e.g., “there’s no such thing as HIV”), defensive avoidance (e.g., “I just don’t want to think about it”), or reactance (e.g., “this is just a government plot”). Thus, when perceptions of threat are strong, high perceptions of efficacy promote danger control actions (self-protective actions) and low perceptions of efficacy promote fear control actions (self-destructive actions).

In short, perceived threat motivates action, perceived efficacy determines the nature of that action. The greater the threat perceived, the greater the behavioral actions, as long as perceptions of efficacy remain stronger than perceptions of threat. However, at some critical point, when people begin to doubt their efficacy in averting the threat, they shift to controlling their fear instead of the danger (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Graphical depictions of the EPPM

Overall, the EPPM suggests that when people feel at-risk for a significant threat (high level of perceived susceptibility and severity), they become scared and are motivated to act. Perceptions of self-efficacy (i.e., perceived ability to perform a recommended response) and response efficacy (i.e., whether or not the recommended response is seen as effective in averting a health threat) determine whether people are motivated to control the danger or control their fear. When people feel able to perform an action that they think effectively averts a threat (strong perceptions of self-efficacy and response efficacy), then they are motivated to control the danger and engage in self-protective health behaviors such as condom use to prevent HIV infection. In contrast, when people either feel unable to perform a recommended response and/or they believe the response to be ineffective (e.g., they believe condoms have holes), they give up trying to control the danger. Instead they control the fear by denying their risk, defensively avoiding HIV/ AIDS issues, adopting a fatalistic attitude, or perceiving manipulation (e.g., “AIDS is a hoax that really is a government plot to repress people”).

Application Of The Theory In Communication Research

The EPPM has been applied to a large variety of topics and populations across different channels. It has been used to guide education entertainment radio dramas, worker notification programs for beryllium exposure, statewide gun safety courses, and is currently used to guide individually tailored counseling in HIV clinics across the nation.

Empirical investigations consistently show the theory predicts behavioral responses as long as cultural definitions of threat and efficacy are taken into account. For example, western industrialized nations tend to focus (with good success) on threats to physical health, whereas in poorer countries, economic or social threats may be more threatening and relevant than physical threats. Further, it is critical that studies measure intended and unintended effects, because in order to distinguish between “no response” to a message versus “fear control response” (which masks as “no response,” because if an individual is in denial they are not adopting a behavioral recommendation), a researcher must measure things like denial, defensive avoidance, and reactance. Specifically, a “fear control response” masks as a “no response” because there is no behavior change, yet in reality, there was a huge defensive response to a message that prevents behavior change.

The EPPM can be used to tailor messages to promote danger control responses via interpersonal channels (as in counselor–client, doctor–patient, or peer educator encounters) or mass media channels (as in a public service announcement or entertainment education programs).

References:

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59, 329 –349.

- Witte, K. (1993). Message and conceptual confounds in fear appeals: The role of judgment methods. Southern Communication Journal, 58, 147–155.

- Witte, K. (1994). Fear control and danger control: An empirical test of the extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 61, 113 –134.

- Witte, K. (1998). Fear as motivator, fear as inhibitor: Using the extended parallel process model to explain fear appeal successes and failures. In P. A. Andersen and L. K. Guerrero (eds.), The handbook of communication and emotion: Research, theory, applications, and contexts. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, pp. 423 – 450.

- Witte, K., & Roberto, A. (in press). Fear appeals and public health: Managing fear and creating hope. In L. Frey and K. Cissna (eds.), Handbook of applied communication research.

- Witte, K., Meyer, G., & Martell, D. (2001). Effective health risk messages: A step-by-step guide. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.