Attitudes have long been a focus of study by social scientists. In the first edition of the Handbook of social psychology in 1935, Gordon Allport referred to attitudes as an indispensable concept for social psychology. Today, attitudes have become an essential concept for the social sciences. Attitudes, defined as an evaluative response to an object or thing, are critical to the study of persuasion; person perception; reactions to politicians, racism, and stereotyping; responses to the media; and so on. This article will provide an overview of the nature of attitudes and how to measure them, summarize the tripartite model of attitudes, and review recent research on explicit and implicit attitudes.

The Nature Of Attitudes

In everyday talk in English, when someone is said “to have an attitude,” it generally means the person takes a negative or critical view of the world. However, for social scientists, the standard definition of an attitude is simply that it is a hypothetical construct involving the evaluation of some object. First, attitudes are hypothetical constructs because they cannot be directly observed. Rather, attitudes are measured indirectly through a variety of different measures. Second, attitudes involve evaluations of how positively or negatively a person judges something. This evaluation can stem from any number of sources including a person’s beliefs, behavior, and affective reactions to the object. Third, attitudes are directed toward some object or thing. In this instance, “object” is broadly defined and can include things such as Diet Coke or convertible cars, ideas such as democracy or postmodernism, individuals such as your neighbor or groups of people such as foreigners, and so forth. The key point is that attitudes are directed at something.

Earlier definitions of attitudes included additional characteristics of attitudes that are not included in the current definition. In particular, attitudes were typically thought to be relatively enduring. But research now indicates that attitudes can be very sensitive to the context in which the attitude is expressed. In different contexts, people will express different attitudes. Further, literally thousands of studies on persuasion have attested to the fact that attitudes can be changed – sometimes fairly easily – and the result of the persuasion attempt is a changed attitude. According to more traditional definitions of attitudes, the changed attitude would not be an attitude because it was not enduring. Another development in thinking about attitudes involved the functions that attitudes serve for people.

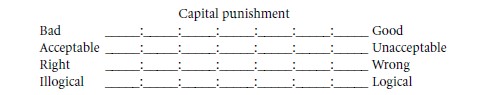

While there are numerous different ways to measure attitudes, two methods are particularly common. The first is a semantic differential scale. A semantic differential scale involves having people judge their evaluation of an object along a scale anchored at each end by polar opposite adjectives, e.g., good/bad. Consider the following scales designed to measure someone’s attitude toward capital punishment:

Figure 1

A person with an extremely positive attitude toward capital punishment should be more likely to check near “good,” “acceptable,” “right,” and “logical,” while a person with a more neutral attitude might check positions in the middle between the two adjectives depending on whether the attitude was slightly positive or negative, and a person with an extremely negative attitude should be more likely to place checks near “bad,” “unacceptable,” “wrong,” and “illogical.”

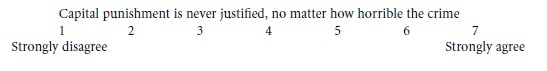

The second way attitudes are measured involves Likert scales. Likert scales present a statement and having people indicate how much they agree or disagree with the statement. The following Likert scale could be used to measure attitudes toward capital punishment.

Figure 2

Persons with more positive attitudes toward capital punishment are more likely to disagree with the statement and to circle 1, 2, or 3, depending on how positive their attitude is toward capital punishment. Conversely, a person with a negative attitude toward capital punishment would be more likely to agree with the statement and to circle one of the higher numbers. A person with a neutral attitude would circle 4, indicating they neither agree nor disagree with the statement.

Recent research and theorizing on attitudes suggests that they may be more complex than these scales indicate. For instance, people can have ambivalent attitudes. Attitude ambivalence refers to situations where people simultaneously have both positive and negative evaluations of an object. Consider the giving of blood. A person may have a positive attitude toward giving blood because it is an altruistic act, but at the same time, he or she may have a negative attitude toward giving blood because it hurts and makes him or her feel queasy. To measure attitude ambivalence, two Likert scales can be used. Both are anchored at the neutral point (or 0): the first asks a person to judge only the positive aspects of the object (a 0 to 3 scale), while the second asks the person to judge only the negative aspects of the object (a 0 to −3 scale). Using the example of giving blood, a person may circle 2 on the positive scale and −2 on the negative scale. A further limitation of semantic differential and Likert scales is that there are other characteristics of attitudes that they do not capture, such as how confidently the person holds the attitude or the accessibility of the attitude from memory.

Tripartite Model Of Attitudes

Early definitions of attitudes usually held that attitudes were comprised of three elements: affective, behavioral, and cognitive. While definitions of attitudes have shifted to simply specifying attitudes as evaluations, this evaluation is generally thought to encompass these cognitive, behavioral, and affective components. The beliefs one has about an attitude object, how one acts toward the object, and how one feels about the object are most often thought of as the main components of an attitude. The tripartite model of attitudes has been extremely influential in shaping research and theorizing on attitudes. Research now suggests that these three components of attitudes can influence the development of attitudes which, once formed, can influence affect, behavior, and cognition.

The affective component of an attitude is the emotional or visceral reaction to the attitude object, that is, one’s feeling that the object is good or bad. The “yuck” reaction to a cockroach involves the affective component of the attitude. There are many different ways that affective reactions can be learned including classical and operant conditioning. Classical conditioning, for example, simply involves repeated associations of positive or negative feelings with the attitude object. This example demonstrates how affective responses to an object influence the development of an attitude, but strong attitudes can also influence the affective reactions that people have when encountering that object. As people develop more extreme or stronger attitudes toward a politician, they will begin to have stronger affective reactions to that politician.

The behavioral component of an attitude refers to the actions taken in regard to the attitude object. This is the component that has historically been considered the most important. The initial justification for studying attitudes was that they predict behavior. And, while the relationship between attitudes and behavior is complex, attitudes do predict behavior in many instances. Likewise, research has shown that people’s behavior influences their attitudes. People who do not have well-formed attitudes may look at their behavior to determine if they have a positive or negative attitude toward an object. For example, people may not have strong feelings about a particular band, but when asked whether or not they like it, they may consider that they listen to the band frequently because a room mate listens to it, and they don’t ask the room mate to turn off the music, and therefore they reason that they must like the band. Likewise, dissonance theory predicts that if people engage in behavior that is very inconsistent with their attitudes, they may change their attitudes to be consistent with the behavior.

The cognitive component is generally thought to encompass the thoughts and beliefs related to the attitude object. Some people argue that beliefs and attitudes are the same thing. For example, how is the belief that Diet Coke tastes good different from a positive attitude toward Diet Coke? The distinction between attitudes and beliefs is that beliefs are often thought of in terms of how likely they are to be true (e.g., Diet Coke typically tastes good unless the syrup is mixed incorrectly). However, it would seem strange to talk about an attitude as being true most of the time. The beliefs about an object will influence what a person’s attitude is toward the attitude object. The preponderance of pro or antithoughts is a good indication as to whether the attitude is favorable or unfavorable toward an issue. However, it is also important to note that attitudes can influence the beliefs that people develop. For example, attitudes can bias how information is processed so that people are more likely to accept information that is consistent with their attitude or to distort information so as to make it consistent with their attitude.

Implicit And Explicit Attitudes

An important distinction that has recently emerged in the study of attitudes involves explicit versus implicit attitudes. This distinction arose from research on stereotyping and racism where it was found that people’s explicitly stated attitudes and beliefs were not racist, but that oftentimes their behavior would display subtle forms of racism. The racist behavior reflected implicit associations that the person had developed between a certain group and negative attitudes. Out of this research grew the idea that people can have both explicit attitudes that they can readily express and implicit attitudes that are more difficult to express, but can influence the person’s affect, behavior, and cognitions just as explicit attitudes do.

More recently, research has suggested that explicit attitudes reflect a person’s beliefs. These explicit attitudes are easy to measure using traditional paper and pencil measures such as those discussed above. Furthermore, they appear to be easy to change using standard persuasive techniques. Implicit attitudes, on the other hand, reflect associations between the attitude object and various affective reactions such as fear that have been learned over time. Measures of implicit attitudes are more complex than measures of explicit attitudes and typically involve some type of task that measures how long it takes a person to make various kinds of judgments such as the tasks that are used to measure attitude accessibility. Currently, there is little consensus on how to change implicit attitudes (Gawronski & Bodenhausen 2006).

References:

- Albarracin, D., Johnson, B. T., & Zanna, M. P. (eds.) (2005). The handbook of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (ed.), A handbook of social psychology, vol. 2. Worcester, MA: Clark University Press, pp. 798 – 844.

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Gawronski, B., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2006). Associative and propositional processes in evaluation: An integrative review of implicit and explicit attitude change. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 692 – 731.

- Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century, 2nd edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Priester, J. R., & Petty, R. E. (1996). The gradual threshold model of ambivalence: Relating the positive and negative basis of attitudes to subjective experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 431– 449.

- Stiff, J. B., & Mongeau, P. A. (2003). Persuasive communication, 2nd edn. New York: Guilford.