The transtheoretical model is an integrative model of behavior change, combining key constructs from other theories. The model describes how people modify a problem behavior or acquire a positive behavior. It has been very influential in guiding the design of behavior change interventions during the last two decades. The central organizing construct of the model is the stages of change theory. The model also includes a series of independent variables, the processes of change, which are 10 cognitive and behavioral activities that facilitate change, and a series of intermediate outcome measures, including the decisional balance inventory, self-efficacy or situational temptations scale, and behavior measures.

The transtheoretical model is a model of intentional change. The specific focus of the model is on behavior change and the key constructs are dynamic variables, i.e., open to modification, whereas more static variables such as gender and past history are included only as moderator variables. In addition, the model primarily focuses on the decision-making of the individual where other approaches to health promotion study social or biological influences on behavior. The model has been previously applied to a wide variety of problem behaviors. Smoking cessation has been the most widely studied application and will be used for illustration here.

Stages Of Change: The Temporal Dimension

The stage construct is the key organizing construct of the model. It is important in part because it represents a temporal dimension. Change implies phenomena occurring over time. Behavior change was often construed as an event, such as quitting smoking, drinking, or overeating. The transtheoretical model views change as a process involving progress through a series of five stages.

Pre-contemplation is the stage in which people are not intending to take action in the foreseeable future. In smoking cessation, pre-contemplation is the stage where the person is currently smoking and not intending to quit in the next six months. People may be in this stage because they are uninformed or under-informed about the consequences of their behavior. Or they may have tried to change a number of times and become demoralized about their ability to change. Both groups tend to avoid reading, talking, or thinking about their high risk behaviors.

Contemplation is the stage in which people are intending to change their behavior. For smoking, contemplation is the stage where the person is currently smoking but intends to quit in the next six months. Contemplators are more aware of the pros of changing than pre-contemplators but are also acutely aware of the cons. This balance between the costs and benefits of changing can produce profound ambivalence that can keep people stuck in this stage for long periods. We often characterize this phenomenon as chronic contemplation or behavioral procrastination.

Preparation is the stage in which people are intending to take action in the immediate future, usually measured as the next month. For smoking, preparation is the stage where the person is currently smoking but intends to quit in the next month. They also have made some changes in the target behavior in the last year, such as reducing the number of cigarettes or making a quit attempt. These individuals typically have a plan of action, such as consulting a counselor, talking to their physician, buying a self-help book, or purchasing a pharmacological aid such as nicotine replacement therapy.

Action is the stage in which people have made specific overt modifications to the behavior. For smoking, action is the stage where the person has quit smoking in the last six months. The person will make numerous changes to their personal environment to maintain the change and, since action is observable, the behavior change will be recognized by others. The action stage is defined as lasting for six months because of the relapse curves reported across a wide variety of behaviors but this definition may need to be modified for behaviors such as mammography screening where women are recommended to undergo screening every one to two years.

Maintenance is the stage in which people have maintained the change for at least six months. For smoking, maintenance is the stage where the person has quit smoking and has maintained that change for at least six months. People in maintenance no longer have to work as hard to maintain the change, are less tempted to relapse and are increasingly more confident that they can continue their change.

Two different concepts are employed to define the stages. Before the target behavior change occurs, the temporal dimension is conceptualized in terms of behavioral intention. After the behavior change has occurred, the temporal dimension is conceptualized in terms of duration of behavior change. Regression occurs when individuals revert to an earlier stage of change. Relapse is one form of regression, involving regression from action or maintenance to an earlier stage.

Determining When Change Occurs

Theories often focus on only a single outcome measure of success. From smoking cessation research, point prevalence smoking cessation serves as an example of a single outcome measure (Velicer et al. 1992). These measures are not sensitive to change over all possible stage transitions. Point prevalence for smoking cessation would be unable to detect an individual who progresses from pre-contemplation to contemplation, from contemplation to preparation, or from action to maintenance. In contrast, the transtheoretical model involves a series of intermediate/outcome measures, proposes a multivariate outcome space, and includes measures that are sensitive to progress through all stages. These constructs include the pros and cons from the decisional balance inventory, self-efficacy or temptation, and the target behavior (Velicer et al. 1996).

The two constructs of the decisional balance inventory (Velicer et al. 1985) reflects the individual’s relative weighing of the importance of the pros and cons of changing. It is derived from Janis and Mann’s (1977) model of decision-making. A predictable pattern has been observed relating the pros and cons to the stages of change. In pre-contemplation, the cons of smoking cessation far outweigh the pros. In contemplation, these two scales are about equal. In the advanced stages, the pros of quitting outweigh the cons. However, a different pattern has been observed for the acquisition of healthy behaviors.

The situational self-efficacy/situational temptations construct represents the situationspecific confidence that people have in order to cope with high-risk situations without relapsing to their unhealthy or high-risk habit (Velicer et al. 1990). This construct was adapted from Bandura’s (1977) self-efficacy theory. Research into relapse prevention can be measured with a confidence or temptations response format. The temptation format measures the intensity of urges to engage in a specific behavior when in difficult situations. The self-efficacy format measures the confidence of the individual not to engage in a specific behavior across a series of difficult situations.

The intermediate/dependent measure outcome space also includes behavioral measures that are specific to the problem. For example, in smoking cessation the behavioral outcome measure would include such widely employed measures as point prevalence smoking cessation, number of cigarettes, and time to first cigarette. These are sometimes described as measures of dependence or problem severity.

Independent Measures: How Change Occurs

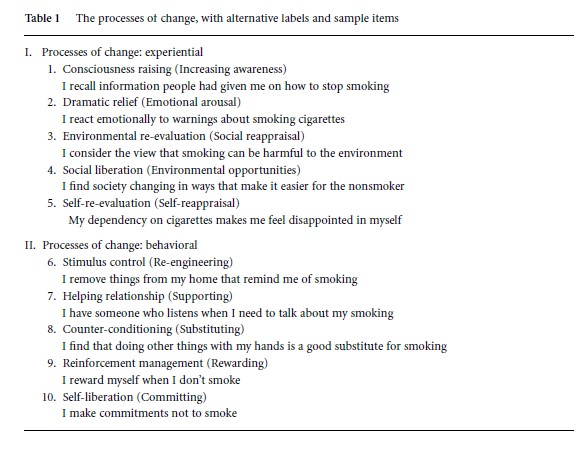

The processes of change are the covert and overt activities that people use to progress through the stages. Processes of change provide important guides for intervention programs, since the processes are the independent variables that people need to apply, or be engaged in, to move from stage to stage. Ten processes have received the most empirical support in our research to date (Prochaska et al. 1988). The first five are classified as experiential processes and are used primarily for the early stage transitions. The last five are labeled behavioral processes and are used primarily for later stage transitions. Table 1 provides a list of the processes (together with alternative labels) with a sample item for each process from smoking cessation.

For smoking cessation, each of the processes is related to the stages of change by a curvilinear function. Process use is at a minimum in pre-contemplation, increases over the middle stages, and then declines over the last stages. The processes differ in the stage where use reaches a peak. Typically, the experiential processes reach peak use early and the behavioral processes reach peak use late.

APPLICATIONS

The transtheoretical model has had a strong influence on all aspects of intervention development and implementation. It has been particularly appropriate for researchers who want to intervene on total populations. One new intervention approach where the transtheoretical model has been widely employed is expert system or computer-tailored interventions (Noar et al. 2007; Velicer et al. 2006).

Table 1 The processes of change, with alternative labels and sample items

Use of the transtheoretical model can affect all aspects of an intervention: recruitment, retention, progress, and outcome. For recruitment, the model makes no assumption about how ready individuals are to change. It recognizes that different individuals will be in different stages and that appropriate interventions must be developed for everyone. As a result, very high participation rates have been achieved (see Velicer et al. 2006).

The model can produce high retention rates, since the model is designed to develop interventions that are matched to the specific needs of the individual. Since the interventions are tailored to their individual needs, people drop out less frequently because of inappropriate demand characteristics. The model can provide sensitive measures of progress, since it includes a multivariate set of outcome measures that are sensitive to a full range of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral changes and recognize and reinforce smaller steps than traditional action-oriented approaches. This is particularly important in the early stages where progress typically does not involve easily observed changes in overt patterns of behavior. The model can support a more appropriate assessment of outcome. Interventions should be evaluated in terms of their impact (recruitment rate X efficacy) since interventions based on the transtheoretical model have the potential to have both a high efficacy and a high recruitment rate.

The transtheoretical model should be viewed as a work in progress. It represents an attempt to integrate the diverse components of existing theories. One of the important advances that resulted from adding the temporal dimension, i.e., the stages of change, was that theories previously viewed as conflicting could now be integrated. However, an integrative theory cannot ever be viewed as finished, since an important new construct can emerge at any time, when a new version of the model will be required to integrate that construct. Beyond the addition of new constructs, the measures of the current constructs are being continuously evaluated and updated. New empirical evidence about the relationships between the constructs and the similarities and differences across different areas of application is an ongoing activity.

References:

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. PsychologicalReview, 84, 191–215.

- Janis, I. L., & Mann, L. (1977). Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice and commitment. New York: Free Press.

- Noar, S. M., Benac, C. N., & Harris, M. S. (2007). Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 673 – 693.

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390 – 395.

- Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 38 – 48.

- Prochaska, J. O., Velicer, W. F., DiClemente, C. C., & Fava, J. L. (1988). Measuring the processes of change: Applications to the cessation of smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 520 –528.

- Velicer, W. F., DiClemente, C. C., Prochaska, J. O., & Brandenberg, N. (1985). A decisional balance measure for assessing and predicting smoking status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1279 –1289.

- Velicer, W. F., DiClemente, C. C., Rossi, J. S., & Prochaska, J. O. (1990). Relapse situations and selfefficacy: An integrative model. Addictive Behaviors, 15, 271–283.

- Velicer, W. F., Prochaska, J. O., Rossi, J. S., & Snow, M. (1992). Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 23 – 41.

- Velicer, W. F., Rossi, J. S., Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1996). A criterion measurement model for addictive behaviors. Addictive Behaviors, 21, 555 –584.

- Velicer, W. F., Prochaska, J. O., & Redding, C. A. (2006). Tailored communications for smoking cessation: Past successes and future directions. Drug and Alcohol Review, 25, 47–55.