It is widely recognized that cultural norms, values, beliefs, and practices vary among population sub-groups, and influence how members of a group seek, understand, process, communicate, and act upon information about health. Ignoring these cultural differences during health and medical system interactions can have serious consequences that lead to or exacerbate disparities in health status between population sub-groups.

Critical reviews examining the relationship between cultural competence and health disparities recommend a wide range of communication-based strategies to help eliminate disparities, including improved patient– provider communication, interpreter services, health literacy enhancement, clearer signage and forms, and culturally appropriate health education materials and health promotion and disease prevention programs (Brach & Fraser 2000; Betancourt et al. 2003; Institute of Medicine 2004). Yet surprisingly little is known about whether, or the extent to which, taking culture into account in such planned health communication efforts increases their effectiveness. A 2002 Institute of Medicine report on health communication strategies for diverse populations concluded that there is an urgent need for comparative studies of the effects of health communication interventions that address and ignore diversity factors, like culture (Institute of Medicine 2002).

Approaches To Achieving Cultural Appropriateness In Health Communication

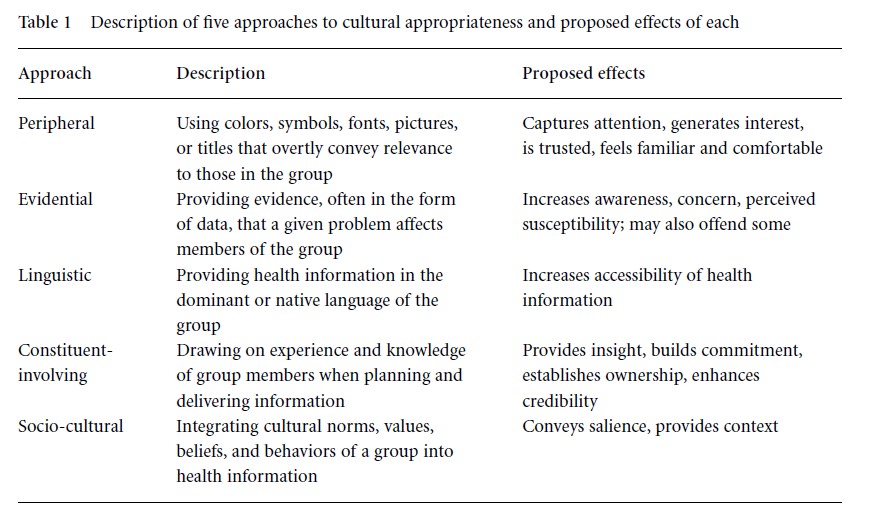

Although evidence for their effectiveness may not be clearly established, at least five approaches are commonly used to achieve cultural appropriateness in health communication (Kreuter et al. 2003).

Peripheral Approaches

Peripheral approaches “package” health information in ways likely to appeal to a given group. The term “peripheral” is used in reference to the elaboration likelihood model’s explanation of the non-central route of information processing, which suggests that characteristics such as the superficial elements of culture described here can, under certain circumstances, lead to attitude change when included in a persuasive communication. Specific tactics include integrating colors, images, fonts, pictures of group members, or declarative titles (e.g., “A guide for African-Americans”) into health communication materials designed for a given group. By reflecting culture in the design elements of programs and materials, health communication developers hope to attract attention and convey relevance. Peripheral approaches tend to focus on expressions of culture that are visible and accessible to those outside the culture, like social rituals, traditional dress, language patterns, and cuisine.

Effective use of peripheral approaches should enhance receptivity to and acceptance of health communication materials (Resnicow et al. 1999). Although a mechanism for this effect has not yet been demonstrated empirically, graphic design and visual literacy scholars propose that the language of colors, images, and pictures is immediately perceptible, and to the right audience will feel familiar and comfortable, be trusted, and may generate interest in or attention to the information.

Evidential Approaches

Evidential approaches to cultural appropriateness in health communication seek to increase the perceived relevance of a health issue by presenting population-specific evidence of its impact to members of the group. Usually such evidence takes the form of statistics and/or probability statements. For example, health information designed to motivate lesbians to be screened for breast and cervical cancer might emphasize that lesbians have lower rates of mammography and Pap testing than other groups of women, and higher rates of breast and cervical cancer.

Evidential statements are generally designed to raise awareness, concern, and/or perceived vulnerability to a particular problem by showing that it affects a group to which a person belongs. Research based on Weinstein’s precaution adoption process model lends support to this explanation, showing that those who perceived a problem to affect others like them were more likely to think about the problem, decide to take preventive action, and actually make plans to do so. But using certain types of group-specific evidence may have unintended and detrimental effects. Compared to exposure to the same evidence framed in a positive way, exposure to evidence that one’s group is doing worse than another group can elicit more negative and fewer positive reactions to health information, and lower the group’s intent to prevent the problem.

Linguistic Approaches

Linguistic approaches seek to make health information more accessible by providing it in languages spoken or read by different cultural groups. Because language is so fundamental to effective communication, linguistic accessibility is arguably the most fundamental dimension of culturally appropriate health communication. In clinical health-care settings, linguistic approaches may involve providing translator services or hiring multilingual providers. Similarly, creating culture-specific health communication programs or materials can involve adapting existing content or developing original content. When translating existing health information to another language, maintaining the meaning and effectiveness of the original (i.e., fidelity) is a particular challenge, and can be difficult to achieve reliably in a straight translation task. Linguistic approaches also include efforts to incorporate into health communication the specific terminology, colloquialisms, and figures of speech used by a cultural group, even if they are not in a foreign language.

Constituent-Involving Approaches

Constituent-involving approaches seek to assure cultural appropriateness by drawing on the experiences of members of a cultural group to be reached. Adhering to principles of community participation and audience involvement is fundamental to health communication planning, and requires identifying substantive, decision-making roles for members of the cultural group during all phases of communication development. It may also include hiring staff members indigenous to the cultural group and training paraprofessionals or “natural helpers” from the group. Involving constituents can provide insight into deeper levels of culture such as underlying rules and assumptions that are known and understood by members of the group, but seldom shared with outsiders or accessible to communication scientists and practitioners from outside the culture. Their ideas, involvement, and commitment can often be applied to optimize the other four approaches to achieve cultural appropriateness in health communication.

Socio-Cultural Approaches

Socio-cultural approaches present health information in the context of cultural values and beliefs held by the intended audience. When key elements of culture can be identified and incorporated into health communication messages, sources, and channels, they can convey salience to the group’s members. For example, framing the benefits of a given health action in terms of faith or family may make the information more meaningful to those in cultures that value collectivism and spirituality. Thoughtfully executed sociocultural approaches to health communication will reflect an understanding of culturally normative practices and beliefs – the inner workings of culture rather than the outward appearances emphasized in peripheral approaches.

There is some recent evidence that socio-cultural approaches enhance effectiveness of traditional health communication interventions. In a randomized trial among lower-income African-American women from urban public health centers, those who received health information tailored to their behavioral beliefs and cultural values were more likely to get mammograms and increase daily fruit and vegetable consumption than those who received information tailored to behavioral beliefs or cultural values alone, or a usual-care control group (Kreuter et al. 2005).

Outlook

A summary of each approach and its proposed effects on communication outcomes is provided in Table 1. Further development and empirical testing of these hypotheses will enhance our understanding and application of culturally appropriate health communication. For intervention planners, the question may not be which of these approaches to use, but rather how best to integrate multiple approaches in a single health communication program. At present, however, this does not appear to be a normative practice. In a recent review of injury prevention interventions targeting racial or ethnic minorities, only 11 percent used three or more approaches to cultural appropriateness (Parks et al. 2006). Constituent-involving approaches were used most often (in 61 percent of interventions), but only one in four interventions used peripheral, evidential, linguistic, or sociocultural approaches. While the review identified exemplars of multidimensional cultural appropriateness in interventions conducted in New Zealand and the US, these stood out as exceptions.

Table 1 Description of five approaches to cultural appropriateness and proposed effects of each

Although progress has been steady since the 2002 Institute of Medicine report, there remain substantial gaps in the science of culture and health communication and significant need for applying evidence-based approaches to cultural appropriateness in health communication practice. Both represent excellent opportunities for current and future health communication professionals.

References:

- Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., & Ananeh-Firempong, O. (2003). Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Reports, 118(4), 293 –302.

- Brach, C., & Fraser, I. (2000). Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Medical Care Research and Review, 57(suppl. 1), 181–217.

- Institute of Medicine (2002). Speaking of health: Assessing health communication strategies for diverse populations. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Institute of Medicine (2004). Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Kreuter, M. W., & Haughton, L. T. (2006). Integrating culture into health information for African American women. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(6), 794 – 811.

- Kreuter, M. W., & McClure, S. M. (2004). The role of culture in health communication. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 439 – 455.

- Kreuter, M. W., Lukwago, S. N., Bucholtz, D. C., Clark, E. M., & Sanders-Thompson, V. (2003). Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education and Behavior, 30(2), 133 –146.

- Kreuter, M. W., Skinner, C. S., Holt, C. L., et al. (2005). Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African American women in urban public health centers. Preventive Medicine, 41(1), 53 – 62.

- Parks, S. E., & Kreuter, M. W. (2006). Cultural appropriateness in interventions for racial and ethnic minorities. In L. S. Doll, S. E. Bonzo, J. A. Mercy, D. A. Sleet, & E. N. Haas (eds.), Handbook of injury and violence prevention. New York: Springer, pp. 449 – 462.

- Resnicow, K., Baranowski, T., Ahluwalia, J. S., & Braithwaite, R. L. (1999). Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity and Disease, 9(1), 10 –21.