Classroom instructional technology (CIT) includes the pedagogical tools and methods that allow educators to communicate instructional messages that achieve instructional goals and facilitate learning outcomes at all educational levels in classrooms around the world. Over the past three decades, researchers have studied both the challenges and the opportunities associated with the potential of CIT to enhance effective delivery of instruction in the classroom. Researchers have also aimed to understand how pedagogical tools are used to enhance student learning. When integrated appropriately into the teaching and learning process, CIT functions to enhance knowledge sharing, student engagement and collaboration, and classroom interaction, and ultimately to support learning. Studies also demonstrate, however, that CIT is least effective and can be detrimental to student learning when it is not intentionally integrated into a meaningful instructional strategy, and when it does not further a specific educational goal (Kadiyala & Crynes 2000).

Definitions and Concepts

There is no single or universally accepted definition for CIT but the term can be broadly understood from a combined teacher–student perspective as “the way teaching is done and how learning is accomplished.” Technology is often used incorrectly as a synonym for computers. While computer hardware and software provide powerful tools for creating, recording, analyzing, and transmitting a wide variety of instructional messages, they are certainly not the only CIT that should be considered. Any tool that can potentially support student learning, including chalk, pencils, whiteboards, textbooks, overhead projectors, and televisions, is an example of CIT. Communicating instructional messages that achieve instructional goals can be performed using message creation and manipulation tools, organization and presentation tools, information search, and resource management tools. CIT also includes iPods for podcasting, presentation graphic programs, disciplinespecific software programs and tutorials, and the incorporation of the Internet as an integral part of the course curriculum.

Technology is used to distribute materials, handle logistics, and provide students with access to other students and the instructor. It can be used to foster open communication and active learning, clarify course expectations, provide individualized attention to students, and facilitate the collection of assignments and document sharing. Furthermore, when implemented appropriately, technology has been used to increase student contact with course materials, peers, and with the professor outside of the classroom.

The Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) defines instructional technology as “the theory and practice of design, development, utilization, management, and evaluation of processes and resources for learning” (Seels & Richey 1994). From that vantage, instructional technology and the teaching process are synonymous and difficult to distinguish. Communication researchers instead claim that the difference between knowing and teaching is communication, and that CIT is best conceptualized as the tools, media, and conduit (medium) through which clear and relevant instructional messages are communicated. The impact of CIT use on classroom communication, therefore, may vary in part as a function of course type and the ways in which instructors use technology to achieve different instructional objectives.

Practical Considerations on the Use of Classroom Instructional Technology

Lane and Shelton (2001) have argued that throughout higher education, and particularly within the communication discipline, too many educators are latching onto the most recent wave of technological advances without fully considering fundamental CIT dimensions, practical issues, and evaluative pedagogical criteria that should be used to determine whether pedagogical tools can be used for effective delivery of instruction. Before CIT is integrated into any classroom, several strategic decisions about course objectives, curriculum, and the features of the technology must be considered.

Among these decisions are the determination of precise learning objectives – what students are expected to be able to do when they have completed the course or unit of instruction, and what the students need to know in order to meet behavioral expectations. It is also critical to ascertain what students already know and what knowledge they bring to the classroom, as well as to assess whether students can use their knowledge effectively. Effective integration of technology into the teaching and learning process must include consideration of key CIT features that would help educators make an informed decision about whether technology supports teaching and learning objectives, as well as how and when to use CIT, which squarely puts pedagogy before technology. It is necessary for educators to have a clear understanding of the available CIT features (e.g., text, audio, multimedia, storage, etc.) and how each could function to achieve instructional objectives, as well as a strong rationale for why the new CIT would improve the dimensions currently available in the status quo. One of the most important issues related to CIT integration is an accurate assessment of whether the teachers and students possess the requisite competencies and experiences to ensure an appropriate fit between the CIT, the instructional messages, and the course objectives. It is also necessary to have confidence in the flexibility of the CIT to allow for individual differences in teaching styles, student abilities, and learning styles. Finally, educators must consider whether the CIT will be reliable and available with consistent quality.

The practical considerations that can be potential barriers when implementing CIT include an analysis of whether the CIT is cost effective while providing access for all students, whether the integration of technology supplements and enhances the curriculum without becoming the focus of the curriculum, and an assessment of the intended and unintended consequences of CIT use. Educators have learned that purchasing computer technology (i.e., hardware and software) without budgeting for installation and training is a costly mistake.

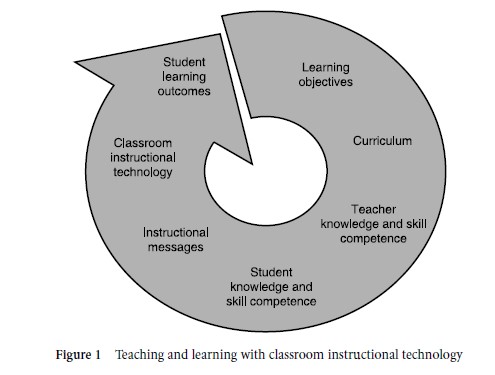

A useful conceptual model to illustrate how technology can be successfully integrated into the classroom environment begins with a focus on learning objectives and the related curriculum, moves to a consideration of teacher and student knowledge and skill competencies, followed by the creation of tailored instructional messages that are communicated through appropriate CIT, and results in intentional student learning outcomes that accomplish the initial learning objectives (Fig. 1).

Evaluative pedagogical criteria should be employed based upon cost–benefit and assessment standards to determine whether the CIT succeeded in reaching its potential to enhance effective delivery of instruction in the classroom, and to understand how the pedagogical tools were used to enhance student learning. For example, the quality, appropriateness, and effectiveness of program tools, techniques, and materials that are presented as part of the curriculum should be assessed.

Research on Classroom Instructional Technology

Several theories have been applied to investigations of CIT. Media richness analysis demonstrated that different technological channels (e.g., multimedia, audio only) may lead to different performance outcomes (Timmerman & Kruepke 2006). Attribution theory has been tested to demonstrate how instructor credibility and caring are enhanced when instructional technology is incorporated into the classroom (Schrodt & Witt 2006). Gender theory has been used to explain why females are more likely than males to equate technology use with instructor competence (Schrodt & Turman 2005). Distributed learning theory allows educators to compare traditional curriculum presentation without technology with the same curriculum incorporating technology (Walker 2003). More applied research has investigated the benefits of textbook technology supplements (Sellnow et al. 2005) and the incorporation of podcasts to increase student engagement and interest, while allowing for more time for classroom discussions and lectures (Huntsberger & Stavitsky 2007).

Although anecdotal and descriptive research has been plentiful, empirical evidence regarding the effects of technology on student learning is largely absent. Oppenheimer (1997, 45) has argued, “there is no good evidence that most uses of computers significantly improve teaching and learning.” The studies that have been completed are largely anecdotal and lack the necessary scientific controls to be conclusive.

National, state, and local standards require teachers around the world to integrate technology into an already crowded curriculum. In New Zealand, a model of teacher development in technology education was integrated into several primary and secondary classrooms to demonstrate best practices for how teachers develop advanced competencies in technological knowledge and an understanding of technological practice (Jones & Compton 1998). In 2005, the Minister of Education in Japan approved a national curriculum of technology education that was similar to the curricular standards established by the International Society for Technology in Education (www.iste.org). The competencies are generally related to “what students should know and be able to do to learn effectively and live productively in an increasingly digital world” (ISTE 2007). The International Technology Education Association (iteaconnect.org) is based in the United States but has international centers in Australia, Chile, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Scotland, Spain, and Taiwan. Kimbell (1997) provides an overview and comparison of the international trends in technological curriculum and assessment in the UK, Germany, the United States, Taiwan, and Australia.

CIT has the potential to enhance a solid curriculum developed by a trained professional. Research that focuses on establishing the primacy of one instructional strategy over another should include considerations of the intended educational goal and corresponding instructional messages, and the extent to which a specific technology is best used to convey the intended message. The communication discipline can neither turn away from any mode of communication, nor can it practice an educational philosophy that is not grounded in practical use and access issues as well as critical evaluative issues. CIT enhances learning when pedagogy is sound and when there is a clear integration of technology.

Assessing the effects of technology on student learning is a complex process and requires that the strategies used to measure the effects of technology on student learning outcomes be appropriate to the learning outcomes promoted by those technologies. Instructional communication researchers will continue to document the effects of CIT on student learning outcomes. Of particular import will be whether CIT is related to course goals and objectives, and to what extent the implementation of the CIT supplements and enhances traditional teaching methods to increase student learning outcomes.

References:

- Huntsberger, M., & Stavitsky, A. (2007). The new “podagogy”: Incorporating podcasting into journalism education. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 61, 397– 410.

- ISTE (2007). National educational technology standards for students: The next generation. At https://www.kelloggllc.com/tpc/nets.pdf.

- Jones, A., & Compton, V. (1998). Towards a model for teacher development in technology education: From research to practice. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 8(1), 51– 65.

- Kadiyala, M., & Crynes, B. L. (2000). A review of literature on effectiveness of use of information technology in education. Journal of Engineering Education, 89(2), 177–189.

- Kimbell, R. (1997). Assessing technology: International trends in curriculum and assessment: UK, Germany, USA, Taiwan, Australia. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Lane, D. R., & Shelton, M. W. (2001). The centrality of communication education in classroom computer-mediated communication: Toward a practical and evaluative pedagogy. Communication Education, 50, 241–255.

- Oppenheimer, T. (1997). The computer delusion. Atlantic Monthly, 280(1), 45 – 62.

- Schrodt, P., & Turman, P. D. (2005). The impact of instructional technology use, course design, and sex differences on students’ initial perceptions of instructor credibility. Communication Quarterly, 53, 177–196.

- Schrodt, P., & Witt, P. L. (2006). Students’ attributions of instructor credibility as a function of students’ expectations of instructional technology use and nonverbal immediacy. Communication Education, 55, 1–20.

- Seels, B. B., & Richey, R. C. (1994). Instructional technology: The definition and domains of the field. Washington, DC: Association for Educational Communications and Technology.

- Sellnow, D. D., Child, J. T., & Ahlfeldt, S. L. (2005). Textbook technology supplements: What are they good for? Communication Education, 54, 243 –253.

- Timmerman, C. E., & Kruepke, K. A. (2006). Computer-assisted instruction, media richness, and college student performance. Communication Education, 55, 73 –104.

- Walker, K. (2003). Applying distributed learning theory in online business communication courses. Business Communication Quarterly, 66(2), 55 – 67.

Back to Educational Communication.