At present, there are over 50,000 international organizations with a total budget easily over US$250 billion devoted to improving social, economic, political, and health conditions around the world, specifically in less developed countries (Directory of Development Organizations 2007). The current status of modern international development organizations can be traced back to the end of World War II and the official launch of the United Nations. Indeed, while other organizations predate the UN, including religious and political bodies, it was the formation of the UN and its many subsidiary programs and funds that helped catalyze international modernization efforts.

Modern History of Development Institutions

This launch also coincided with the establishment of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Bretton Woods System in 1944. While the Marshall Plan for post-World War II recovery focused on bilateral agreements made with individual European countries, Bretton Woods created a multilateral system that provided economic aid to developing countries through loans that were tied to changes in economic policies in the recipient countries (Spero & Hart 2003).

In the United States the first bilateral assistance to developing countries began with the Truman Point Four program (a Marshall Plan for the third world), which provided skills, information, and equipment from 1950 onwards, and other legislation that led to shortterm assistance. But it was the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 that sought to address longterm world development needs through a bilateral system of loans and grants to be administered through the US Agency for International Development (USAID). To this day, USAID is the primary federal US agency for assisting developing countries. It employs a wide range of communication strategies to support its programs of disaster relief, poverty eradication, and democratic reform (Melkote & Steeves 2001).

During the Cold War era from 1947 to 1989, development aid was offered according to east/west ideological principles. One of the most obvious examples of this was the Peace Corps, initiated by John Kennedy in 1960. During this period, political rhetoric was often part and parcel of communication strategies employed by development agencies. The US development efforts closely followed foreign policy objectives, frequently tying aid to US technology, experts, and communication systems.

In Europe, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) was one of the earliest organizations to establish a goal of supporting economic development both within and outside its 30 member countries. Established in 1948 to coordinate the Marshall Plan as the Organization for European Economic Cooperation, OECD has emerged to offer its assistance to more than 70 developing countries. One of its major programs is in the promotion of information and communication technologies in sustainable economic growth and social welfare.

Once the Soviet Union began to fragment in the early 1990s, communication research and development organizations experienced a substantial paradigm shift. Largely absent from the communist/capitalist geopolitical framework, international development organizations lost their status as central to governmental policy focus, and hence the economic support for many of their activities. However, nongovernmental organizations, now grouped with trade unions, faith-based organizations, community groups, indigenous peoples’ organizations, and foundations under the umbrella title of civil society organizations, have increased their activity in development assistance (Mody 2003).

Missions of Development Institutions

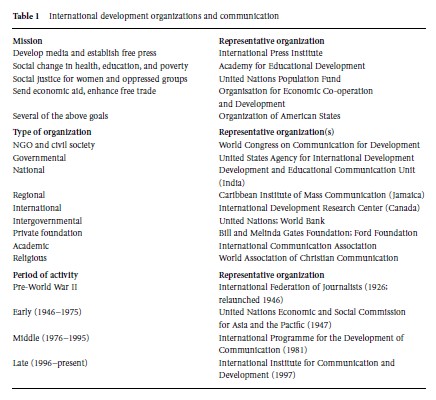

Many of these organizations use communication strategies and support communication projects in their work. These organizations operate at the international, regional, national, and community levels (see Table 1). A far-reaching group of organizations have made it their priority to develop media organizations and work for a western-style free press. These efforts include funding for infrastructure, training for the use and maintenance of such networks, and education for journalists and citizens alike in creating and using media for democratic ends (Wilson 2004). Additionally, some organizations work to insure that journalists who speak or write against the government are not treated unfairly, imprisoned, or executed.

Civil society organizations focusing on communications, such as Panos (working with journalists and other communicators) and CFSC (Communication for Social Change Consortium), were created as networks of smaller organizations in order to increase the potential impact across more countries and with greater resources addressing a wider range of development issues. Other groups organized around networks of faith, like the World Association for Christian Communication, made up of a range of ecumenical Christian funding partners, focus on communication as a human right.

Since the diffusion of communicative technologies, most recently the Internet, has been shown to be linked to advances in education, health, and income, many international development organizations began to re-emphasize the importance of communication in their strategies. The United Nations made the information society the theme of one of its major world summits in 2003 and 2005, thus pointing other international development agencies in this direction and drawing in technology-based organizations, such as the Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility and various countries’ Internet societies, to focus on development issues (Carpentier & Servaes 2006).

Another common mission is to effect social change in health-care and practices and in education, and to reduce poverty. In some instances, local programming is created in an effort to match cultural needs and norms. These efforts, such as the UNESCO-sponsored Sara campaign, directed to the education needs of young girls in Sub-Saharan African countries, are to be lauded, but may exceed their target audiences and reduce their effectiveness when exported multination ally. Many international organizations focus on solving particular problems, such as AIDS, illiteracy, or child welfare. Others support particular groups, such as migrants or indigenous peoples. Some of these organizations cross national borders, while others work at local levels within particular countries, such as the Rainforest Action Network.

Still others operate only at the national or local level. One such organization in India, the Self-Employed Women’s Association, established in 1972, grew out of a trade union for textile workers. In order to promote the rights of women workers, this organization has used a range of communication technologies to disseminate information and tell the stories of women workers’ successes to other workers. Based on its successes in India, SEWA organizers have helped spread the movement to South Africa, Yemen, and Turkey. Though SEWA was begun as a gender-based organization, it has widened its focus to home workers and vendors in other countries.

Finally, there are a number of international development organizations with goals that encompass all, or a number of, the above-mentioned areas and using a wide range of frameworks in their approaches. These supra-mission organizations are usually well funded and have great discretion in choosing projects and locations as well as extending or restructuring their overall mission. Private foundations are able to change their focus frequently, and many organizations within the UN often have sub-programs or organizations under one umbrella to achieve larger goals such as gender equity or access to education (Servaes 1999).

References:

- Carpentier, N., & Servaes, J. (2006). Towards a sustainable information society: Deconstructing WSIS. Portland, OR: Intellect.

- Directory of Development Organizations (2007). Resource guide to development organizations and the Internet. At www.devdir.org/index.html, accessed August 6, 2007.

- Melkote, S. R., & Steeves, H. L. (2001). Communication for development in the third world: Theory and practice for empowerment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mody, B. (2003). International and development communication: A twenty-first-century perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Servaes, J. (1999). Communication for development: One world, multiple cultures. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Spero, J. E., & Hart, J. A. (2003). The politics of international economic relations. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson.

- Wilson, E. (2004). The information revolution and developing countries. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Back to Development Communication.