Texts are vehicles of meaning in human expression and communication. Growing out of centuries of literary, hermeneutic, and other humanistic scholarship, the concept was originally reserved for written and other verbal messages. From the 1960s onwards, however, texts came to denote all meaningful entities, including images, everyday interaction, and cultural artifacts generally, as examined through increasingly interdisciplinary approaches in communication and related fields.

Texts as Communication

Deriving from classical Latin texo (to weave, to construct) and textum (fabric as well as speech and writing), the concept of text directs attention toward the process in which ideas and insights are given concrete shape and offered in communication to others. Compared to the concept of a message, which is commonly said to contain and transmit information, and which is sometimes used interchangeably with text, this latter concept emphasizes that meaning is only articulated in the meeting of form and content, aesthetics, and propositions. Importantly, the meaning of a given text is considered open to questioning and interpretation both by contemporary audiences and by posterity.

The complexity of textual meaning helps to account for the preferred methodologies of the humanities, probing the subtleties and nuances of the individual text for what is being communicated. In a medieval worldview, the Bible provided an analogy to the Book of Nature as a means of insight into the Great Chain of Being (Lovejoy 1936). Since both “books” articulated divine intent, they required scrupulous attention to potentially significant details, as overseen and enforced by church and state authorities. In a modern perspective, meaning could still be said to reside within texts with socially binding implications. Legal contracts as well as entire cultures and sub-cultures are constituted through texts, and their reinterpretation may anticipate fundamental religious or political change.

Texts lend themselves to the immanent analysis of meaning for practical as well as contemplative purposes. As the arts assumed their modern shape as separate social and aesthetic practices in the course of the eighteenth century, the act of interpretation came to be defined programmatically by Immanuel Kant in his Critique of judgment (1790) as the disinterested contemplation of the beautiful, the true, and the good. Artworks could and should be appreciated for their inherent logic, rather than any ulterior purpose. The understanding of texts as singular sources of insight fed into idiographic, individualizing, and qualitative approaches to the study of culture and society. Like artworks and historical events, media texts can be examined for their inherent significance.

Texts in Communication

Studies of texts as communication traditionally have asked: where is meaning – in which content elements and formal structures? Increasingly, communication research has come to explore how texts enter into communication, asking: when is meaning – for whom, and in which contexts (Jensen 1991)?

With reference to this last question, qualitative textual analysis, first of all, makes a distinction between the story and the discourse of a text (Chatman 1989). While the story is the series of events, the what of the text, discourse is the how or actual organization and representation of these events, typically in a narrative, which can be implemented in many different ways, for example, to create suspense. Literary and film theory, further, has emphasized the spectator’s active participation in the creation of textual meaning. Drawing on Russian formalism (Erlich 1955), Bordwell (1985) reintroduced syuzhet to refer to explicit narrative information about events, whereas fabula denotes the audience’s reconstruction of the connections between events. Thus, whereas authors, directors, and other producers offer meaning as a potential in various media and modalities, it remains for readers, viewers, and other audiences to actualize specific meanings. Beyond film and literary theory, qualitative media reception studies in particular have explored empirically how audiences decode textual meaning, depending on social and cultural backgrounds and contexts.

Textual communication in the broadest sense is addressed in content and discourse analysis, which examine how concrete texts are shaped by, and in turn shape, their social settings. The concept of discourse, moreover, has been employed to refer to historically shifting dominant worldviews. In this regard, structuralist and poststructuralist theories of society, e.g., in the work of Louis Althusser and Michel Foucault, have suggested that the construction and distribution of knowledge through texts, media, and other social institutions may be understood as an exercise of power. In an even wider sense, texts can be considered the stuff that social reality is made of: social contexts have been studied literally as texts, for instance, within anthropology and cultural studies.

Intertextuality

The inclusive notion of texts has been elaborated with reference to the concept of intertextuality. The seminal contribution was made by the Russian literary scholar Mikhail Bakhtin and his circle in the early decades of the twentieth century (Bakhtin 1981). Bakhtin’s most basic concept – dialogism– was translated by Kristeva (1984) as intertextuality, and underscores the fact that individual signs only acquire their meaning in relation to other signs, past as well as present. Texts are not stable containers of meaning; instead, texts should be taken as the momentary manifestations of textuality, articulating a cultural heritage and historical tradition. The point is that all human acts of communication enter into structures and configurations that follow distinctive cultural patterns. A culture might be considered an almost infinitely complex instance of intertextuality.

The methodological question of how to examine intertextual structures and the social processes shaping them has tended to divide researchers. The majority of studies derive from literary and film studies, and have centered on, for instance, novels, films, or television series as relatively self-contained entities – texts as communication – with explicit or, more commonly, implicit references to previous artworks, symbols, themes, or genres. Genette (1982/1997) has been an influential representative of this position, referring to what he calls transtextuality; for example, metatextual relations hinting at the origins of certain textual constituents and paratextual relations between a novel and its explanatory cover text.

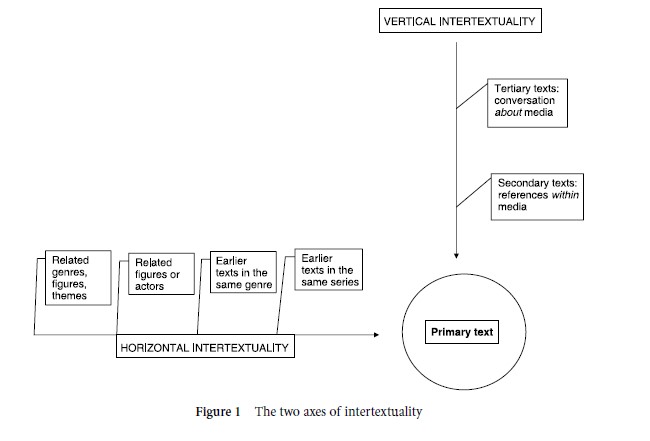

Conceiving intertextuality as an operational way of approaching texts in communication, as well, Fiske (1987) distinguished between two dimensions of intertextuality. Horizontal intertextuality covers the transfer and accumulation of particular meanings over historical time, as preserved in the metaphors, characters, and styles of traditional arts as well as popular media. Vertical intertextuality, in comparison, operates during a more delimited time period, but extends across several media and social contexts. To specify this synchronic perspective, Fiske identified three categories of texts. Primary texts are carriers of significant insight in their own right. (In the horizontal perspective, the primary texts are the center of attention.) If the primary text, for example, is a new feature movie, the secondary texts will consist of studio publicity, reviews, and criticism. And the tertiary texts are produced by audiences who engage in conversation with each other, before, during, and after attending the movie.

In combination, the two axes of intertextuality amount to a model of how meaning is produced and circulated in society, reinserting the concept of texts into the agenda of communication studies (Fig. 1). At the same time, Fiske’s (1987) terminology still privileged media texts as the primary sources of meaning in communication. A few major contributions have applied the intertextual perspective to popular cultural phenomena such as James Bond (Bennett & Woollacott 1987) and Batman (Pearson & Uricchio 1990), with further attention to, for instance, their place in popular memory. Also the flow of broadcasting has lent itself to studies of how viewers (and listeners) select and combine discursive elements from multiple channels into an intertextual configuration (for overview, see Jensen 1994).

Hypertextuality

The rise of digital media and of more differentiated forms of communication has given the theoretical concept of intertextuality renewed importance, also for empirical studies of media use (Bolter 1991; Aarseth 1997). So-called hyperlinks, connecting message elements in computer-mediated communication, may be understood as instrumental or operationalized forms of intertextuality – a means of making explicit, retrievable, modifiable, and communicable what might have remained a more or less random association in the minds of recipients. Hypertexts (or their constituent parts) can be linked for easy access or for purposes of indexing. Similarly, hypermedia join, for instance, video sequences with verbal explanations, to be selected and activated by learners and other groups of users.

While some work on hyperstructures has tended to overestimate their potential for social innovation or political liberation (e.g., Landow 1997), the concepts of hypertextuality and intertextuality hold significant potential for future theory development as well as for concrete analyses of technologically mediated communication. On the one hand, hypertextuality facilitates distinctive kinds of navigation and intervention by users within more flexible systems of communication. On the other hand, users of hypertext systems still engage in a process of interpretation, as informed by intertextual clues and implicit links, which is broadly similar to audiences’ encounters with images and verbal texts in print and previous electronic media. Building on the classic concept of texts, communication research may retain both a sensitivity to meaning as complex and contextual, and an openness to the shifting technological and institutional conditions of human communication.

References:

- Aarseth, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on ergodic literature. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Bennett, T., & Woollacott, J. (1987). Bond and beyond. London: Methuen.

- Bolter, J. D. (1991). Writing space: The computer, hypertext, and the history of writing. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bordwell, D. (1985). Narration in the fiction film. London: Methuen.

- Chatman, S. (1989). Story and discourse: Narrative structure in fiction and film, 5th edn. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Erlich, V. (1955). Russian formalism: History, doctrine. The Hague: Mouton.

- Fiske, J. (1987). Television culture. London: Methuen.

- Genette, G. (1997). Palimpsests: Literature in the second degree (trans. C. Newman & C. Doubinsky). Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press. (Original work published 1982).

- Jensen, K. B. (1991). When is meaning? Communicaton theory, pragmatism, and mass media reception. In J. Anderson (ed.), Communication yearbook, vol. 14. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Jensen, K. B. (1994). Reception as flow: The “new television viewer” revisited. Cultural Studies, 8(2), 293–305.

- Kristeva, J. (1984). Revolution in poetic language. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Landow, G. P. (1997). Hypertext 2.0: The convergence of contemporary critical theory and technology, 2nd edn. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lovejoy, A. O. (1936). The great chain of being. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pearson, R., & Uricchio, W. (eds.) (1990). The many lives of the Batman. New York: Routledge.

Back to Communication Theory and Philosophy.