Semiotics is an interdisciplinary field that studies “the life of signs within society” (Saussure 1959, 16). While “signs” most commonly refer to the elements of language and other symbolic communication, it also may denote any means of knowing about or representing an aspect of reality. Accordingly, semiotics has developed as an affiliate of such traditional disciplines as philosophy and psychology. In the social sciences and humanities, including communication research, semiotics became an influential approach particularly from the 1960s.

Two different senses of “signs” can be traced from the pre-Socratic philosophers, through Aristotle, to St. Augustine. First, the mental impressions that people have are signs that represent certain objects in the world to them. Second, spoken, written, and other external expressions are signs with which people can represent and communicate a particular understanding of such objects to others. The first sense (mental impressions) recalls a classical understanding of signs, not as words or images, but as naturally occurring evidence that something is the case. For example, fever is a sign of illness, and clouds are a sign that it may rain, to the extent that this sign is interpreted by humans. The second sense (means of communication) points toward the modern distinction between conventional signs (verbal as well as formal languages) and sense data, or natural signs. Modern natural sciences could be said to examine natural signs with reference to specialized conventional signs.

The inclusive conception of signs has remained an undercurrent in the history of ideas (Posner et al. 1997–1998). The first explicit statement regarding natural signs and human languages came from St. Augustine (c. 400 ce). This position was elaborated through the European medieval period with reference to nature as God’s Book and an analogy to the Bible, and to all of existence manifesting itself as a Great Chain of Being (Lovejoy 1936). It was not until the seventeenth century, however, that the term “semiotic” first appeared, in John Locke’s An essay concerning human understanding (1690). Locke proposed a science of signs in general, only to restrict his focus to “the most usual” signs, namely, verbal language and logic (Clarke 1990, 40).

Peircean Logic and Semiotic

The American pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce was the first thinker to recover this undercurrent in an attempt to develop a general semiotic (Peirce 1992–1998). He understood his theory of signs as a form of logic, which informed a comprehensive system addressing the nature of being and of knowledge. The key to the system is Peirce’s definition of the sign as having three aspects: “A sign, or representamen, is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign. That sign which it creates I call the interpretant of the first sign. The sign stands for something, its object” (Peirce 1931–1958, vol. 2, 228). An important implication of this definition is that signs always serve to mediate between objects in the world, including social facts, and concepts in the mind. Peirce’s point was not that signs are what we know, but that they are how we come to know what we can justify saying that we know, in science and in everyday life. Thus, Peircean semiotics married a classical, Aristotelian notion of realism with the modern, Kantian position that humans necessarily construct their understanding of reality in the form of particular cognitive and performative categories.

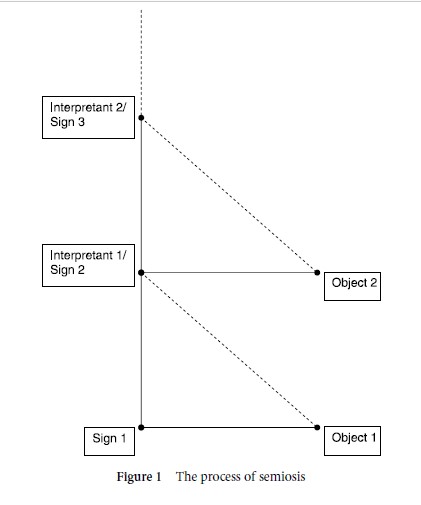

A further implication is that human understanding is not a singular internalization of reality, but a continuous process of interpretation, or what is called semiosis. This is witnessed, for example, in the practice of scientific discovery, but also in the ongoing coordination of social life. Figure 1 illustrates the process of semiosis, noting how any given interpretation (interpretant) itself serves as a sign in the next stage of an infinite process that serves to differentiate humans’ understanding of reality. Although Peirce’s outlook was that of a logician and natural scientist, semiosis also refers to the processes of communication by which cultures are maintained and societies reproduced and, to a degree, reformed.

One of the most influential elements of Peirce’s semiotics outside logic and philosophy has been his categorization of different types of signs, especially icon, index, and symbol. Icons relate to their objects through resemblance (e.g., a realistic painting of a landscape); indices have a causal relation (e.g., a photograph registers a segment of that landscape); and symbols have an arbitrary relation to their object (e.g., a novelist emphasizes specific aspects of the landscape in constituting a verbal narrative). Different kinds of communication research, from discourse analysis to visual communication studies, have employed these types as analytical instruments in order to describe the ways in which humans perceive and act upon reality.

Saussurean Linguistics and Semiology

Compared with Peirce, the other main figure in the development of modern semiotics, Ferdinand de Saussure, focused on verbal language, or what Peirce had referred to as symbols. The main achievement of Saussure was to outline the framework for contemporary linguistics. In contrast to the emphasis that earlier philology had placed on the diachronic perspective of how different languages change over time, Saussure proposed to study language as a system in a synchronic perspective. Language as an abstract system (langue) could be distinguished, at least for analytical purposes, from the actual uses of language (parole). The language system has two dimensions. Along the syntagmatic dimension, letters, words, phrases, etc. are the units that combine to make up meaningful wholes. Each of these units has been chosen as one of several possibilities along a paradigmatic dimension; for example, one verb in preference to another. This combinatorial system helps to account for the unique flexibility of language as a means of expression and a medium of social interaction.

To be precise, Saussure referred to the broader science of signs not as semiotics, but as semiology. Like Locke, and later Peirce, Saussure drew on classical Greek to coin a technical term. The two variants are explained, in part, by the fact that Peirce and Saussure had no knowledge of each other. In Saussure’s own work, the program for a general semiology remained undeveloped, appearing almost as an aside from his main enterprise of linguistics. It was during the consolidation of semiotics as an interdisciplinary field from the 1960s that this became the agreed term, overriding Peirce’s “semiotic” and Sausure’s “semiology,” as symbolized by the formation in 1969 of the International Association for Semiotic Studies. It was also during this period that Saussure’s systemic approach was redeveloped to apply to culture and society.

One important legacy of Saussure has been his account of the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign. This sign type is said to have two sides, a signified (concept) and a signifier (the acoustic image associated with it). Whereas this notion is sometimes construed in skepticist and relativist terms, as if communicators were paradoxically free to choose their own meanings, and hence almost destined to stay divorced from any consensual reality, the point is rather that the linguistic system as a whole, including the interrelations between signs and their components, is arbitrary, but fixed by social convention. When applied to studies of cultural forms other than language, or when extended to the description of social structures as signs, the principle of arbitrariness has rekindled classic debates concerning the relationship between signs and their referents.

Semiotics in Communication Research

It was the application of semiotics to questions of meaning beyond logic and linguistics that served to consolidate semiotics as a recognizable, if still heterogeneous field from the 1960s. Drawing on several other traditions of aesthetic and social theory, this emerging field began to specify what studying “the life of signs within society” might mean. The objects of analysis ranged from artworks and mass media to the life forms of premodern societies, but studies were united by a common interest in culture in the broad sense of worldviews that orient social action. The work of Claude Lévi-Strauss (1963) on structural anthropology was emblematic and highly influential of such research on shared, underlying systems of interpretation that might explain the viewpoints or actions of individuals in a given cultural context. It was Saussure’s emphasis on signs as a system, then, that provided the model for structuralist theories about social structure and power, and about the human unconscious as a “language”.

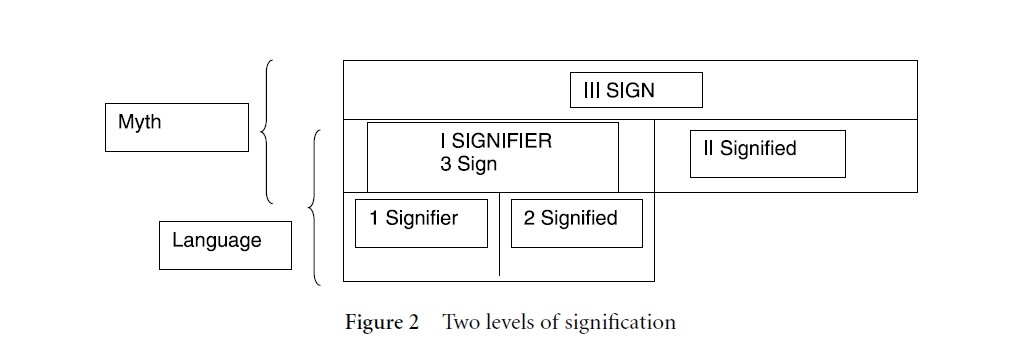

Of the French scholars who were especially instrumental in this consolidation, Roland Barthes, along with A. J. Greimas (Greimas & Courtés 1982), stands out as an innovative and systematic theorist. Barthes’s model of two levels of signification or semiosis, reproduced in Figure 2, has been one of the most widely copied attempts to link concrete sign vehicles, such as texts and images, with the social “myths” or ideologies that they articulate. Building on Louis Hjelmslev’s formal linguistics, Barthes (1973) suggested that the combined signifier and signified (expressive form and conceptual content) of one sign (e.g., a magazine picture of a young black man in a French uniform saluting the flag) may become the expressive form of a further, ideological content (e.g., that French imperialism was not a discriminatory or oppressive system). Barthes’s political agenda, shared by much semiotic scholarship since then, was that this semiotic mechanism serves to naturalize particular worldviews, while obscuring others, and should be exposed analytically.

In retrospect, one can distinguish two ways of appropriating semiotics in social, cultural, and communication research. On the one hand, semiotics can be treated as a methodology for examining signs, whose social or philosophical implications are interpreted with reference to another set of theoretical concepts. On the other hand, semiotics may also supply the theoretical framework, so that images, psyches, and whole societies are understood not just in procedural but also in conceptual terms as signs. The latter position is compatible with one variant of semiotics that assumes that biological and even cosmological processes are also best understood as semioses. This ambitious and arguably imperialistic extension of logical and linguistic concepts into other fields has encountered criticism, for example, in cases where Saussure’s principle of arbitrariness has been taken to apply to visual communication or to the political and economic organization of society.

A semioticization of, for instance, audiovisual media can be said to neglect their appeal to radically different perceptual registers, which are, in certain respects, natural rather than conventional (e.g., Messaris 1994). Similarly, a de facto replacement of major parts of social science by semiotics may exaggerate the extent to which signs and texts, rather than material and institutional conditions, determine the course of society, perhaps in response to semioticians’ political ambition of making a social difference through a critique of signs. In recent decades, these concerns, along with criticisms of Saussurean formalism, have informed attempts to formulate a social semiotics, integrating semiotic methodology with other social and communication theory (e.g., Hodge & Kress 1988; Jensen 1995).

A final distinction within semiotic studies of society and culture arises from the question of what is a “medium”. Media studies have drawn substantially on semiotics (Bignell 2002) to account for the distinctive sign types, codes, narratives, and modes of address that enter into different technological media (newspapers, television, Internet, etc.) as well as their characteristic modalities (speech, writing, still images, etc.). A particular challenge has been the moving images of the film medium, which was described by Metz (1974) not as a language system, but as a “language” drawing on several semiotic codes. In an extended sense, semioticians have described common objects and artifacts as vehicles of meaning, taking inspiration from, for example, Lévi-Strauss. One rich example is Barthes’s (1985) study of the structure of fashion, as depicted in magazines.

Semiotics and Theory of Science

The conjunction of theoretical abstraction with analytical concretion helps to explain the continuing influence of semiotic ideas since antiquity. The understanding of signs as evidence for an interpreter of something else that is at least temporarily absent, articulated in Aristotle’s writings, and as an interface that is not identical with the thing that is in evidence to the interpreter constitute cultural leaps that have made possible scientific reflexivity and social organization beyond the here and now. The sign concept, equally, has promoted the distinction between necessary and probable relations, as in logical inferences. Illness is a necessary condition of fever, but clouds are only a probable sign of rain. Empirical communication research is mostly built on the premise that probable signs can lead to warranted inferences.

The relationship between theory of signs and theory of science has been explored primarily from a Peircean perspective. For one thing, Peirce himself made important contributions to logic and theory of science. For another thing, the wider tradition of pragmatism has emphasized the interrelations between knowledge, communication, and action, and has recently enjoyed a renaissance at the juncture of philosophy and social theory. By contrast, the Saussurean tradition has frequently bracketed issues concerning the relationship between signs and reality, sometimes retreating into postmodernist skepticism, even if critical research in this vein has recruited other social and cultural theories to move semiology beyond the immanent analysis of signs.

For future communication research, semiotics is likely to remain a source of inspiration, as it has been for almost 2,500 years. The record from the past century of intensified interest in theories of signs, however, suggests that the field is not likely to develop into a theoretically coherent discipline. Instead, in addition to providing a systematic methodology for studying the human uses of signs, semiotics offers a meta-framework for understanding how different research traditions, fields, and disciplines conceive of their analytical objects, data, and concepts. The semiotic heritage offers means of reflexivity regarding the life of signs in society as well as in sciences.

References:

- Barthes, R. (1973). Mythologies. London: Paladin.

- Barthes, R. (1985). The fashion system. London: Cape.

- Bignell, J. (2002). Media semiotics: An introduction, 2nd edn. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Clarke, D. S. (1990). Sources of semiotic. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Greimas, A. J., & Courtés, J. (1982). Semiotics and language: An analytical dictionary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Hodge, B., & Kress, G. (1988). Social semiotics. Cambridge: Polity.

- Jensen, K. B. (1995). The social semiotics of mass communication. London: Sage.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural anthropology. New York: Penguin.

- Lovejoy, A. O. (1936). The great chain of being. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Messaris, P. (1994). Visual “literacy”: Image, mind, and reality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Metz, C. (1974). Language and cinema. The Hague: Mouton.

- Peirce, C. S. (1931–1958). Collected papers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Peirce, C. S. (1992–1998). The essential Peirce. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Posner, R., Robering, K., & Sebeok, T. A. (eds.). (1997–1998). Semiotics: A handbook of the signtheoretic foundations of nature and culture. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Saussure, F. de (1959). Course in general linguistics. London: Peter Owen.

Back to Communication Theory and Philosophy.