The title of a widely influential 1923 volume, The Meaning of Meaning (Ogden & Richards 1989), suggested the difficulty of capturing the complex connotations of the concept of meaning. The contents of the volume, authored by a linguist and a literary critic, with appendices by anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski and medical doctor F. G. Crookshank, underscored the interdisciplinary roots and relevance of the concept. Meaning applies to issues of perception, cognition, and interaction across the natural, human, and social sciences. In contemporary communication research, meaning is perhaps most commonly associated with humanistic perspectives on the texts of communication and their interpretation by culturally specific audiences. If information denotes a social scientific conception of those specific differences which communication makes in later events, meaning refers to the cumulative and unitary experience that humans derive from participating in processes of communication.

Three Conceptions of Meaning

At least three different notions of meaning have fed into communication research from the history of ideas, paralleling three different understandings of human knowledge (Kjørup 2001, 20 –22). First, in the domain of individual experience and existence, meaning implies a saturated sense of self. Meaning constitutes an identity, a presence, and an orientation toward other people and projects in the world. In ordinary language, one connotation in this regard is “the meaning of life,” as articulated in human consciousness and communication, whether in religious or secular terms. In different forms of communication research, meaning as experienced has been examined as a psychological, sociological, and aesthetic phenomenon. Notwithstanding suggestions by postmodernist philosophy that human subjectivity has no such center or self-identity, every-day as well as scholarly practices normally presuppose a meaningful frame or horizon within which individuals understand “how to go on” (Wittgenstein 1958, no. 154).

Second, meaning is the outcome of innumerable communicative exchanges in a culture or collective, manifesting and being sanctioned through tradition. On the one hand, traditions are meaningful insofar as they tap classic or authoritative insights that have proven their relevance and value over time. On the other hand, traditions become meaningful in relation to the current contexts in which they lend themselves to tasks, interactions, and reflections. If the first conception of meaning is expressed in the Delphi oracle’s admonition to “Know thyself,” this second conception focuses attention on how individuals come to know themselves with reference to meanings beyond themselves.

Third, in the modern period, meaning has become an emphatically contested terrain – an object and a source of reflexivity (Beck et al. 1994). A terminology of “meaning production,” while sometimes used metaphorically, has also been applied literally to both cognition and communication: subjects produce meanings and, by extension, identities for themselves, and, in communication, they jointly accomplish meaningful social realities. Particularly constructivist strands in communication research, such as symbolic interactionism and cultural studies, have emphasized how everyday meaning production not merely reproduces, but also challenges and changes cultural conventions and social structures. In this perspective, meaning is a constitutive component of modern culture and society as such, and the category through which both can be reimagined, whether in political dialogue, aesthetic expression, or scientific thought-experiments.

Meaning as an Object of Communication Research

While all three general notions of meaning – individual–mental, collective–cultural, and contingent–constructivist – enter into diverse traditions of communication research across interpersonal, organizational, and systemic levels of analysis, each notion has lent itself to a variety of definitions. In the domain of individual experience, for example, a cognitivist approach would emphasize procedural aspects of how meaning emerges in consciousness, whereas a phenomenological position rather takes meaning as a preparatory condition of conscious experience. As a manifestation of cultural tradition, meaning may be approached in relatively consensual terms as a shared outlook on the world and as a matter of interpretation between cultures, as in intercultural communication studies, or it may be perceived, as in cultural studies, as a hegemonic position to be contested. And in the perspective of the ongoing structuration of modern society and culture, meaning has been examined as a comparatively stable, if preliminary, meaning product, as embodied in discourse, or as a process orienting people in contexts of action.

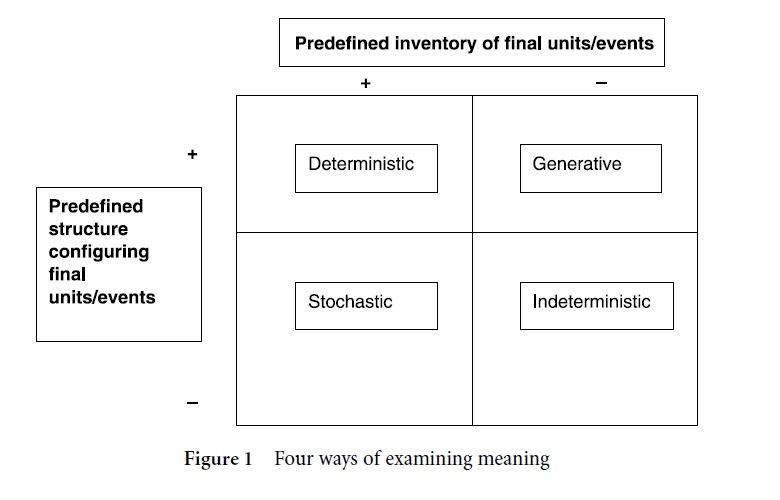

As an analytical object, moreover, meaning has been operationalized in distinctive ways. Figure 1 indicates four ideal-typical ways of examining meaning (Jensen 2002, 30).

The two dimensions of the model address the constituents of meaning and their interrelations, respectively. Meaning arises from the selection and combination of certain elements, even if their characteristics may vary considerably across different forms of expression; for instance, speech, images, and gestures. As a combinatorial structure, the two dimensions give rise to four types or models of meaning. On the one hand, the structure may, or may not, be a fixed matrix configuring the potential outcomes of meaning production. On the other hand, the constituents may, or may not, make up a pre-defined inventory anticipating the units that could possibly result from meaning production. In addition, the terminology of “units/events” allows for empirical research that operationalizes meanings as either vehicles or processes of interchange.

The two main models of meaning in current media and communication research, arguably, are the stochastic and generative types. The stochastic type is witnessed in the prototypical social scientific study in survey, experimental, or content-analytical settings, relying on a hypothetico-deductive methodology. Given a predefined range of content or response units, the question is which of these, and in which configurations, will enter into a particular event space, as measured by an appropriate statistical technique. In other words, the question is when and where – in which discourses and minds – particular meaningful messages manifest themselves.

The generative type is associated with humanistic media studies, typically qualitative analyses of media texts, but also of audience reception and, to a degree, the production of media content, for example, in newsrooms or user-generated content on the Internet. These forms of analysis depart from a pre-defined expressive repertoire – what linguistics and literary theory know as a “deep structure,” for example, grammatical categories or standard components of fairy tales. At the “surface” level of concrete sentences or connected discourse, this matrix may produce an almost infinite variety of meanings.

Even while few researchers explicitly align themselves with either deterministic or indeterministic conceptions of meaning, such models continue to inform the practice of research, sometimes unwittingly. Deterministic models tend to underlie work assuming a direct impact of media on audiences (e.g., Postman 1985). And postmodernist theory implies that both the textual content of media and its interpretation by audiences amount to free-floating, indeterministic processes of meaning (e.g., Fish 1979).

Where and When Is Meaning?

Like information, meaning is often considered as some entity that resides in messages and minds. Rather than asking, “Where is meaning?” – in which spatial location, material vehicle, or psychological domain – it is helpful to ask, “When is meaning?” (Jensen 1991). Just as information theory has refocused attention on the (communicative) difference that (discursive) differences may make in later events, a theory of meaning must address those contexts and practices in which meaning is actualized. In accordance with much twentieth-century philosophy, from Ludwig Wittgenstein to J. L. Austin to Jürgen Habermas, meaning is increasingly associated with action. Whereas meaning may still primarily connote the representation and contemplation of reality, meaning is performative.

A further set of distinctions pertains to the interrelations between meaning and action. First of all, it is important to distinguish between declarative and procedural aspects of meaning as well as of knowledge (Thurlow 2006) – knowing that something is the case, and knowing how to engage this something (Ryle 1949). In empirical communication studies of, for example, attitudes, the declaration of a political preference does not equal an orientation toward action, as in voting. Communication is one way of acting, but people do not necessarily enact what they communicate.

In addition, the distinction between manifest and latent meaning poses notorious difficulties in communication research. The tradition of content analysis was founded on the identification of manifest meanings in media messages (Berelson 1952). Yet one ambition of media studies has been to extract the latent implications of such manifest structures and, next, to establish the uptake of both by audiences. Importantly, latent meanings, while sometimes difficult to ascertain in intersubjectively reliable research designs, are key to diverse cognitive and behavioral consequences of communication. The relationship between manifest and latent meanings has been studied extensively in qualitative communication research, frequently with reference to the concepts of denotation and connotation, which are conceptual analogies to manifest and latent meaning.

Finally, the scale from intentional to incidental meaning involves analytical problems regarding the “when” of meaning: when, specifically, does meaning arise in a process involving senders, messages, and receivers? A core notion of meaning, and of communication as such, is the presentation of intentions by humans to other humans, who may recognize such intentions in one or several turns. In social interaction, however, a communicator is rarely able to control any number of incidental (or perhaps latent) meanings that an audience will add or attribute to his or her intentional (usually manifest) meaning. More or less incidental meanings also abound in natural as well as cultural environments, for example in architecture, which is a socially meaningful organization of people and objects in space. In this regard, human bodies as well as their material environments cannot not communicate (Watzlawick et al. 1967). The main challenge of communication research remains one of specifying how humans and their extensions in information technologies serve as media of meaning in communication.

References:

- Beck, U., Giddens, A., & Lash, S. (1994). Reflexive modernization: Politics, tradition, and aesthetics in the modern social order. Cambridge: Polity.

- Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Fish, S. (1979). Is there a text in this class? The authority of interpretive communities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jensen, K. B. (1991). When is meaning? Communication theory, pragmatism, and mass media reception. In J. Anderson (ed.), Communication yearbook, vol. 14. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Jensen, K. B. (2002). The humanities in media and communication research. In K. B. Jensen (ed.), A handbook of media and communication research: Qualitative and quantitative methodologies. London: Routledge.

- Kjørup, S. (2001). Humanities, geisteswissenschaften, sciences humaines: Eine einführung. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

- Ogden, C. K., & Richards, I. A. (1989). The meaning of meaning: A study of the influence of language upon thought and of the science of symbolism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Postman, N. (1985). Amusing ourselves to death. New York: Viking.

- Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. New York: Hutchinson’s University Library.

- Thurlow, C. (2006). From statistical panic to moral panic: The metadiscursive construction and popular exaggeration of new media language in the print media. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(3), 667–701.

- Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. H., & Jackson, D. D. (1967). Pragmatics of human communication: A study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes. New York: Norton.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1958). Philosophical investigations. London: Macmillan.

Back to Communication Theory and Philosophy.