Communication inequality refers to differences in the generation, manipulation, and distribution of information among social groups, as well as differences in: (1) access to and use of information channels, (2) attention to media content, (3) recall, knowledge, and comprehension, and (4) capacity to act on relevant information among individuals (Viswanath 2006). The intellectual origins of the communication inequality theory can be traced to the knowledge gap hypothesis by Tichenor et al. (1970), an early formalization of inequalities in communication research. According to this hypothesis, benefits from information flows on a given topic are more likely to be accrued by people of higher socio-economic status compared to people of lower socio-economic status, thus widening the existing gaps rather than narrowing them, drawing attention to the unequal media effects. Subsequently, the term “digital divide” made its way through both scholarly and popular literatures, drawing attention to the unequal access to the Internet among different social groups. Viswanath expanded on these formulations of access to one medium (the Internet) and media effects on knowledge to incorporate the thesis of inequalities across the communication continuum as well as across information delivery systems (Viswanath 2005, 2006). In its current formulation, the communication inequality thesis draws attention to disparities across the communication continuum, starting with access to learning, and the consequences of the disparities. Moreover, it argues that the inequalities may manifest at both individual and group levels.

Dimensions of Communication Inequality

The first dimension of communication inequality relates to differences among individuals and social groups in their access to and use of a variety of information channels. These patterns exist in both developing and developed nations. For example, an assessment of mass media use among a range of African countries suggests that despite recent increases in mass media use overall, the ability to access a broad range of mass media resources is constrained for most individuals, and illiteracy and poverty often impede supply and demand of these resources. Lack of electricity or remoteness may limit the forms of media available (World Bank 2002). Alternatively, illiteracy may restrict access to certain types of media. For example, a recent survey found that in Mozambique, 62 percent of men are literate, compared to 31 percent of women, greatly impacting the types of media they can consume. Similarly, across the continent, most rural populations had higher rates of illiteracy than their urban counterparts.

In developed nations, such as the United States, access to and use of information channels also varies between groups. For example, higher socio-economic groups are more likely to use the Internet for health information (Viswanath 2005). Similar patterns have been found in Germany based on gender, age, level of education, and other socio-demographic characteristics (Kubicek 2004). These inequalities appear to particularly manifest in the access to and use of media that demand recurring expenditures, as well as in complications in use. Often, issues of class, race, and ethnicity may conflate, generating inequalities, particularly in multiracial and multilingual societies.

Attention to media is a significant predictor of knowledge about a given health topic. Inequalities in attention may lead to inequalities across the communication continuum from processing to communication effects. For example, recent data from the Health Information and National Trends Survey (HINTS) conducted by the National Cancer Institute in the United States show that greater attention to health information in newspapers, magazines, and the Internet was linked to higher education levels, though these differences did not present for radio and television.

The growing advances in medicine, science, and technology, despite their immense benefit to humankind, also place greater demands on individuals and institutions that are attempting to understand and use this information. These developments trigger information flows, yet the benefits from the flows accrue unequally among different social classes, as predicted by the knowledge gap hypothesis (Tichenor et al. 1980). Conditions that may deter gaps from opening or widening include inducing or increasing relevance for that information, wide diffusion of information leading to saturation on that topic, the controversial nature of the topic, extensive social ties, participation and involvement in community groups, and use of appropriate information channels (Gaziano 1983; Viswanath & Finnegan 1996).

Inequalities in communication may also manifest in individuals’ and groups’ capacity in using the information. For example, in health, individuals vary a great deal in their ability to use health information to direct their medical and health needs. Part of this problem stems from limited health literacy, an ability to find and use relevant health information to make decisions about one’s health that are consistent with one’s values. The capacity to act on information requires not just individual motivations and skills, but support from the environment and resources to act on the information. For example, mere provision of information about engaging in physical activity is unhelpful if the audience lack access to green space or live in unsafe neighborhoods, conditions that are more likely to be experienced by the poor.

Application of Communication Inequalities: Health Disparities as an Exemplar

The thesis of communication inequality may offer one potent explanation for inequalities that exist in other aspects of our society. For example, communication inequalities may offer one explanation for widespread disparities in health, an inequity that has been attracting increasing attention from different groups (Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2002b; World Health Organization 2007). Health disparities are disproportionate disease burdens faced by certain social groups, leading to increasing morbidity and mortality. For example, in the US, there is a clear socioeconomic gradient in diabetes, where those in the lowest income group had a prevalence rate of 9.7 percent compared to 3.5 percent among those in the highest income group (Kanjilal et al. 2006). In Bangladesh, the neonatal mortality rate is 1.63 to 2.0 times higher among poor versus rich families (Razzaque et al. 2007).

Social epidemiology, the study of social determinants of population distributions of health, offers several explanations for such disparities, including social cohesion, social class or socio-economic status, social networks, work environment and life transition, neighborhood and residential conditions, and social policies, among others (Berkman & Kawachi 2000). Yet, while a number of explanations have been offered to suggest why these “social determinants” may contribute to health disparities, the precise mechanisms linking social determinants with individual and population health are yet to be delineated.

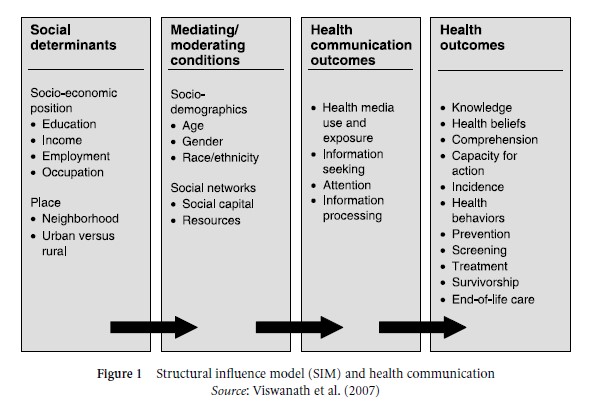

Viswanath et al. (2007) offered the structural influence model (SIM) of communication to connect social determinants to final health outcomes through communication (Fig. 1). The model posits that health outcomes and health disparities can be explained by understanding how (1) structural determinants such as socio-economic status and geography, and (2) mediating mechanisms such as gender, age, and social networks, lead to (3) differential communication outcomes, such as access to and use of information channels, attention to health content, recall of information, knowledge and comprehension, and a capacity to act on relevant information among individuals. Structural antecedents such as socio-economic status and geography influence both the information environment and resources for consumption, leading to differential communication behaviors, which in turn may affect actions along the public health continuum, including knowledge, prevention, detection and treatment, survivorship, and quality of life. Health disparities, therefore, may be explained partly by inequalities along the communication continuum resulting in a cumulative effect on ultimate health outcomes.

Future Directions

Despite innovations in information delivery systems and their speedy diffusion, inequalities are unlikely to ease or disappear. Constant innovations demand continuous and recurrent investment in information delivery services, placing demands on one’s discretionary incomes. Moreover, people make conscious choices as to how they allocate money to different communication services, including entertainment and telecommunication services. Yet communication is a social function. Individuals’ tastes, interests, and needs are shaped and influenced by their immediate orbit, including their social networks, significant peers, class interests, group norms, and perceptions about their leadership roles. Moreover, choices are made within certain constraints of availability of degree of discretion and calculations about relative costs. Thus, choices in both subscriptions to media services and exposure to content are still influenced by socio-economic status and social networks.

Further work in this area will have to elucidate such issues as:

- How can information be targeted to underserved groups while accounting for structural barriers to access?

- What are the obligations of institutions such as government and public and private sectors to ensure that current and future policies and innovations do not widen communication inequalities?

- The constant change and improvement in technologies of information delivery systems assume – or, in fact, may even demand – frequent investment in new technologies. Is this likely to be a deterrent for those who cannot afford to update their technologies as is warranted by the development of new systems?

- Is the increasing sophistication in using and operating the new technologies likely to leave certain groups at a disadvantage? What are the downsides, if any, in not using new information delivery systems?

- What are the implications of interactive effects of technologies and formats on attention and learning among different populations groups, and specifically, on their impact on communication inequalities?

- What are the implications of social and communication policies on communication inequalities?

These questions have acquired a sense of urgency given the characteristics of our epoch, which is sometimes called the “information age.” In the so-called “information age,” inequalities in communication are as invidious as inequities that exist in wealth, health, and power.

References:

- Berkman, L. F., & Kawachi, I. (2000). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2005). National diabetes fact sheet. At https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/factsheets.html.

- Gaziano, C. (1983). The knowledge gap: An analytic review of media effects. Communication Research, 10(4), 447– 486.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2002a). Speaking of health: Assessing health communication strategies for diverse populations. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2002b). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Kanjilal, S., Gregg, E. W., Cheng, Y. J., et al. (2006). Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971–2002. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(21), 2348 –2355.

- Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2000). Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi (eds.), Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kubicek, H. (2004). Fighting a moving target: Hard lessons from Germany’s digital divide programs. IT and Society, 1(6), 1–19.

- Razzaque, A., Streatfield, P. K., & Gwatkin, D. R. (2007). Does health intervention improve socioeconomic inequalities of neonatal, infant and child mortality? Evidence from Matlab, Bangladesh. International Journal for Equity in Health, 6(4). At www.equityhealthj.com/content/6/1/4, accessed September 6, 2007.

- Rimer, B. K., Briss, P. A., Zeller, P. K., Chan, E. C., & Woolf, S. H. (2004). Informed decision making: What is its role in cancer screening? Cancer, 101(5 suppl.), 1214 –1228.

- Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1970). Mass media and the differential growth in knowledge. Public Opinion Quarterly, 34, 158 –170.

- Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1980). Community conflict and the press. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Viswanath, K. (2005). Science and society: the communications revolution and cancer control. Nature Reviews Cancer, 5(10), 828 – 835.

- Viswanath, K. (2006). Public communications and its role in reducing and eliminating health disparities. In G. E. Thomson, F. Mitchell, & M. B. Williams (eds.), Examining the health disparities research plan of the National Institutes of Health: Unfinished business. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, pp. 215 –253.

- Viswanath, K., & Finnegan, J. R. (1996). The knowledge gap hypothesis: Twenty five years later. In B. Burleson (ed.), Communication yearbook 19. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 187–227.

- Viswanath, K., Ramanadhan, S., & Kontos, E. Z. (2007). Mass media. In S. Galea (ed.), Macrosocial determinants of population health. New York: Springer.

- World Bank (2002). The right to tell: The role of media in economic development. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

- World Health Organization (2007). Commission on Social Determinants of Health. At https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/about_csdh/en/.

Back to Communication and Social Change.